The Trump administration intensified tariff pressure this week, moving to impose 25% levies on Canada and Mexico, and then largely reversing course, and raising the existing Chinese tariffs to 20% across the board. The wide-ranging tariffs are an economic cudgel to achieve political ends, potentially spurring companies to bring manufacturing back to U.S. soil.

But will it work?

Some companies, including Pfizer, have already signaled a willingness to move in that direction. Eli Lilly announced plans to invest $50 billion into refurbishing and building facilities in the U.S. to ramp up domestic manufacturing capabilities following a meeting with President Donald Trump.

However, for generic drug makers, which are hardest hit by Chinese tariffs, slim profit margins and high costs may thwart reshoring efforts, even if they are willing to bring their business elsewhere, said Michael Abrams, managing partner of Numerof & Associates.

“Everybody would agree that not being reliant on foreign sources — and China in particular — is a good idea."

Michael Abrams

Managing partner, Numerof & Associates

“Manufacturers that are opting out of manufacturing certain products because the margins are too thin probably don't have the capital to go and build their own manufacturing facilities here in the U.S.,” he said.

Companies that make branded drugs could simply absorb the price increases from tariffs rather than take on the high cost of a move because the relocation process takes long enough for the political winds to shift, Abrams said.

In addition, it’s still not clear how the tariffs will play out. Some promised tariffs haven’t materialized yet, and the administration has delayed or scaled back implementation on some while granting exemptions for others, creating broad uncertainty.

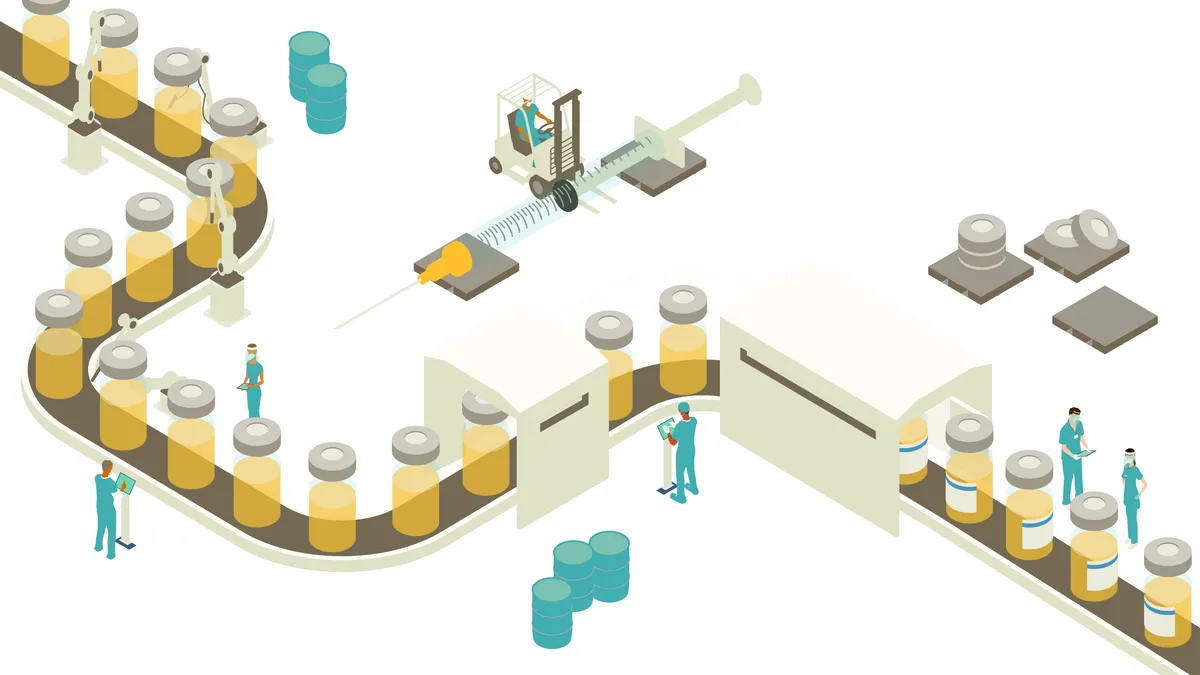

Bringing manufacturing home

The push to bring drug manufacturing back to the U.S. isn’t new or particularly controversial.

“Everybody would agree that not being reliant on foreign sources — and China in particular — is a good idea,” Abrams said, noting that the pandemic dramatically illustrated the risks of foreign dependence.

“When we were experiencing drug shortages is when we became aware that 72% of APIs in our market were coming from overseas,” Abrams said. “It was a bit of a shock to realize how dependent we were, and there was a real push to do something about it.”

Civica Rx, a nonprofit hospital and philanthropic consortium, was one group that moved to boost U.S. generic drug manufacturing capacity. The Biden Administration also put money toward reshoring efforts. Even so, there’s been limited progress.

Companies interested in returning to the U.S. could take advantage of existing manufacturing sites that stood idle for years, Abrams said. One survey of 40 generic drug manufacturing sites found that underutilized facilities could produce 30 billion doses of medicines. However, barriers still exist.

“It really comes down to the money,” Abrams said, specifically labor costs. “Labor has been more expensive in the U.S. and all the associated regulation that goes with it, and I think that's the predominant issue.”

The calculus could change if companies gain incentives to move, such as loans or other options to mitigate the risks of acquiring U.S. facilities, Abrams said.

Companies shouldn’t react too impulsively to the tariffs, said Arda Ural, EY Americas industry markets leader for health sciences and wellness. Investing in U.S. manufacturing sites requires significant capital, and companies should weigh the cost against other priorities, such as stock buybacks, acquisitions or technological investments, he said.

In addition, tariffs could ultimately make borrowing money to invest in manufacturing more expensive if they drive up inflation and delay interest rate cuts.

“Pharma companies, whether they are generics or branded pharmaceuticals, need to wait for the dust to settle before making those massive capital allocations,” Ural said.

Some experts remain skeptical that tariffs are the answer. Steel tariffs enacted during the first Trump administration succeeded in raising domestic prices but didn’t deliver more manufacturing jobs. The latest round may face similar challenges in achieving the intended goal.

“I would say the odds are good that whatever this administration does to encourage reshoring is something that most manufacturers will simply grit their teeth and bear the pain,” Abrams said — because in four years tariffs may no longer be a priority.