"Hope requires action," Sharon King is fond of saying. And her daughter, Taylor, knew all about action.

Taylor was 10 years old when she brought home an application from school for Girls on the Run, a running program for young girls that ends with a 5K race. Taylor was excited to train, but her mother was worried.

"I'm thinking, 'You're blind. You're having seizures,'" King says. "I said, 'Oh, hon, you can't do this.' And she said, 'I will!’"

And she did, with the help of a high school-aged training buddy and safety modifications, despite having CLN1 disease, a type of Batten disease that affects the nervous system.

"She ran that 5k, and in fact, ran another one the following May … and improved her time," King says. "She never let her disease shut her down."

Taylor was diagnosed with the rare disease just before she turned 8, and by the time she passed away at age 20, Taylor had lost her vision, speech, mobility and ability to swallow food. But she never lost her hope, and neither has her mother.

Since Taylor's diagnosis, King has devoted her life to rare disease advocacy. Today, she's manager of advocacy and community engagement at Aldevron, one of the companies at Danaher Corporation. Aldevron produces the materials for gene and cell therapies, such as plasmid DNA, proteins and enzymes.

“If you're a parent, and you have a child with a rare disease, your child's not rare. And your child needs that hope just as much as anyone else.”

Sharon King

Manager of advocacy and community engagement, Aldevron

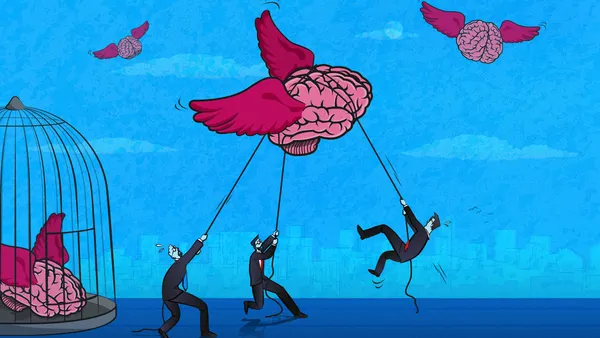

She's especially excited about her new role as a member of the communications sub-team for the Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium (BGTC), which was founded in October 2021 to help with shortcomings in the current drug development model that make it difficult for companies to recover the costs required to develop gene therapies to treat rare and ultra-rare diseases. It's part of the Accelerating Medicines Partnership program, a public-private partnership managed by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH), that includes the NIH, FDA, several pharmaceutical and life sciences companies, and other groups.

King explains that the BGCT hopes to create a development framework template that drives efficiencies around research, manufacturing, regulatory, and other challenges for rare diseases — all with an aim to make developing treatments for these diseases more effective, less expensive and quicker to reach patients.

"Instead of starting from scratch every time, is there a template, a standardized framework that can be followed?" she says. "There are around 7,000 rare diseases and only somewhere between five and 600 of them have an FDA-approved treatment right now. We can do better."

Diagnosis day

Like so many parents of children with rare diseases, King remembers "diagnosis day" vividly. It was late July in 2006, and despite the heat and humidity of a North Carolina summer, she and her husband sat in stunned silence in their car for more than an hour. Along with the devastating news, the geneticist had given them another blow, telling them there was nothing anyone could do for Taylor "in her lifetime and likely in your lifetime."

"I don't think we talked. I don't think there were tears. I think we were literally in shock. And after about an hour, I remember looking at my husband and saying, 'I can't watch this happen to her. I just can't sit and let it happen without doing something. This geneticist says there's nothing we can do. Well, this is my child. There is something,'" she says.

That's the approach that so many parents in the rare disease community take, King says. Yet every single family seems to start from scratch in their fight to raise awareness, get funding and search for treatments. Often, patients and families are working toward finding solutions along pathways that are frustratingly narrow and littered with obstacles.

"That's why I'm so excited about what the Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium can bring. It can make these pathways more clear, so that patients do not have to continue trailblazing over and over," she says. "It is my hope that it's going to help clear some of these hurdles that patients and families are having to jump time and time again."

For the next child

Although a disease itself might be considered "rare" by doctors, scientists and researchers, King knows from experience that when it's happening in your own family, it doesn’t feel that way.

"If you're a parent, and you have a child with a rare disease, your child's not rare. And your child needs that hope just as much as anyone else," she says.

Although King has watched a lot of good progress with gene therapy over the years, she and her family knew that when they started supporting that work, it wouldn’t be for Taylor's benefit.

"It was going to be for the next child," King says.

But she hasn’t lost hope, even after losing her own child.

"Again, hope requires action and hope changes forms. But don't lose hope even as you know your child is not going to survive the illness," she says. "She lived a really good life and we focused on quality of life, giving her the very best life, the very best experiences, and in the meantime contributing to future families of children like Taylor."

In her role at Aldevron, King considers herself a storyteller, connecting the patient experience to the work that her colleagues do every day. Often, their work is relatively far removed from the patients who will eventually benefit from it, but she doesn’t want them to ever lose sight of the people at the end of the line.

"It's my hope that they walk into their role every morning thinking, 'Today, I have the potential to commit to something life changing. And I hope when they leave at the end of the day, that they're thinking the same thing: 'Today I potentially contributed to something transformative, something life changing.' So, I tell those stories and make those connections for them," she explains.

That's also why she enjoys telling Taylor's story and why she has so much hope for the work that BGCT is doing.

"When we collaborate, when we join forces and share our expertise, we can get there better, more efficiently, more effectively," she says. "And we can help more people like my daughter."