Editor’s note: This story is part of our 2022 PharmaVoice 100 feature.

One of Sarah Hersey’s “pet peeves” is being told, “We can’t.” Her response? “Why not? Let’s try.”

To her, that’s what being a pioneer is all about: Trying to solve problems in a unique way, being unafraid to take risks, and challenging the status quo.

She did all three when Bristol Myers Squibb was running a registrational trial in lymphoma that included a precision medicine component.

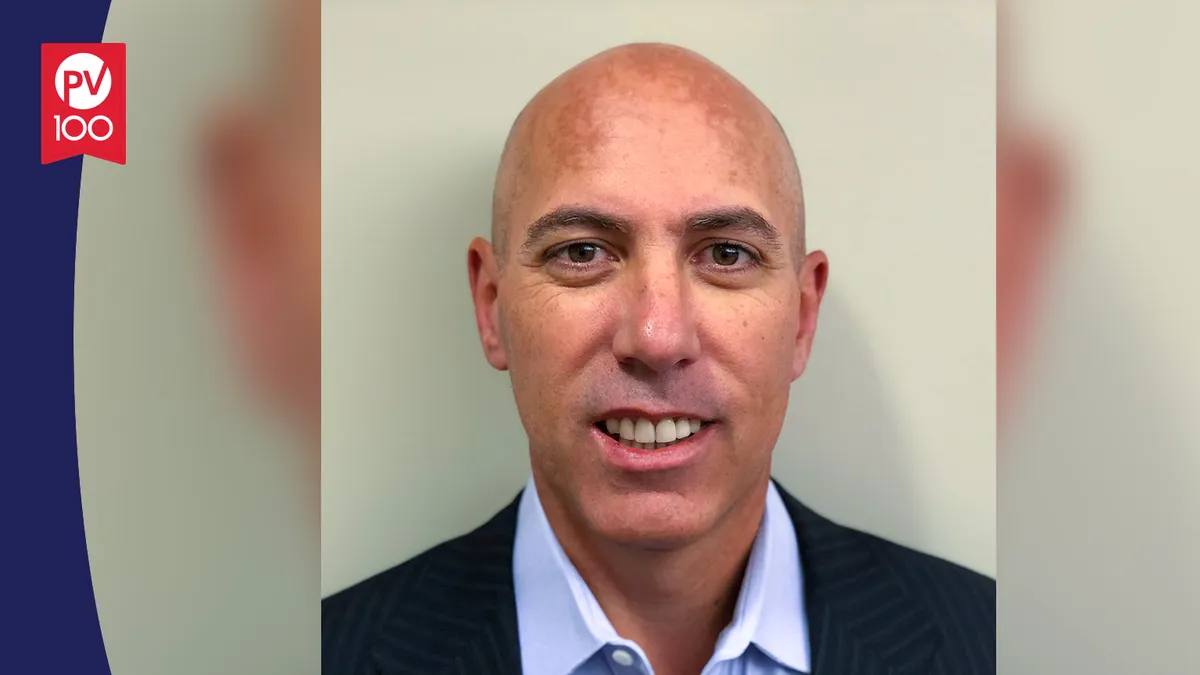

“When I took over the program, one of the first things I noted was that we were using cutting-edge technology,” says Sarah Hersey, vice president, head of translational sciences and diagnostics at Bristol Myers Squibb. “Which is great, right? It’s being a pioneer in the space.”

However, Hersey also noted a problem.

“One of the things that I recognized was that if we stayed the course and only took that approach, we would potentially create a greater disparity gap with regards to adequate access and equity for other individuals and countries that didn't have access to this technology,” she says. “We spent a lot of time — my team and myself — formulating a strategy to be inclusive of all the regions of the world, and that meant identifying and deploying alternate technology solutions.”

However, there were some regions where even those alternate technologies wouldn’t be viable. When she pointed this out, she was met with that pet peeve phrase of hers: “You can’t. People have tried and they’ve never been successful.”

Instead of accepting that and moving on, Hersey asked why they hadn’t been successful, and ultimately developed a solution that was ready to be deployed. And although the trial wasn’t positive, she says it’s a good example of living on the leading edge, pushing back against the norm and striving for success where others have failed.

“It’s kind of challenging that myth behind ‘you can’t do it,’” she says.

Hersey’s leadership has been critical for BMS in building out its precision medicine group, which supports early through clinical stage drug development teams across the organization. She and her team provide important insights about disease biology through delivering clinical-ready assays and diagnostics that help those teams make clearer decisions about which programs to advance into and through the clinic.But BMS is not the only place where she wields her persistent, “outside-the-box” problem-solving style. In fact, her partner often calls her “MacGyver” for the way she makes household repairs, like the “zip-tie matrix” she created when the handle of the lawnmower broke and she couldn’t find a bolt.

“Most people that come into my personal life will say I never do things in the most conventional way,” she says. “When I'm fixing things, I always come at it from an angle that's somewhat unique.”

That kind of attitude has led to pioneering successes too, such as working with the team that brought Oncomine Dx Target Test, the first next generation sequencing (NGS) distributable kit, to market when Hersey was with Novartis.

“One of the most fun types of ‘butterflies’ is seeing good data and being excited about the prospects of what it can mean for patients.”

Sarah Hersey

Vice president, translational sciences and diagnostics, Bristol Myers Squibb

That effort not only required jumping a lot of regulatory hurdles, but collaborating with two rivals: Pfizer and Thermo-Fisher Scientific.

“It was a precompetitive collaboration as well, so not only did we deliver the first NGS distributable kit, we actually did it with our fiercest competitors,” she says.

Partnership, creativity, and challenging others are also central to one of her favorite exercises with her team: “Getting a diverse group of scientists into a room with a whiteboard and [putting] a problem on the board.”

From there, they try to not only come up with solutions, but continually challenge the ideas that are thrown out to vary their thinking and push each other further with each iteration. It’s invigorating and gets their creative juices flowing, but also highlights the importance of collaboration.

“We normally walk away with something none of us would have thought of on our own. And the resultant product from our diverse thoughts is, quite frankly, better than any of us would have achieved alone,” she says. “This requires a unique team and where there's a strong level of trust to be able to challenge one another in a constructive manner…it's impressive the type of creativity that's come out of some of those discussions.”

Hersey says she loves the feeling of “butterflies” when faced with a new challenge, and that “mix of excitement of what could be, peppered in with uncertainty.” She also feels the same excitement when a person she’s mentored is faced with a new opportunity, like submitting work for publication or making a big presentation.

But there’s one kind of fluttery feeling that she especially loves.

“One of the most fun types of butterflies is seeing good data and being excited about the prospects of what it can mean for patients,” she says. “Making a difference for patients is probably on the top of my mind each and every day, and having that focus on patients and bringing it back to the patients is kind of what keeps me motivated, keeps me driven.”