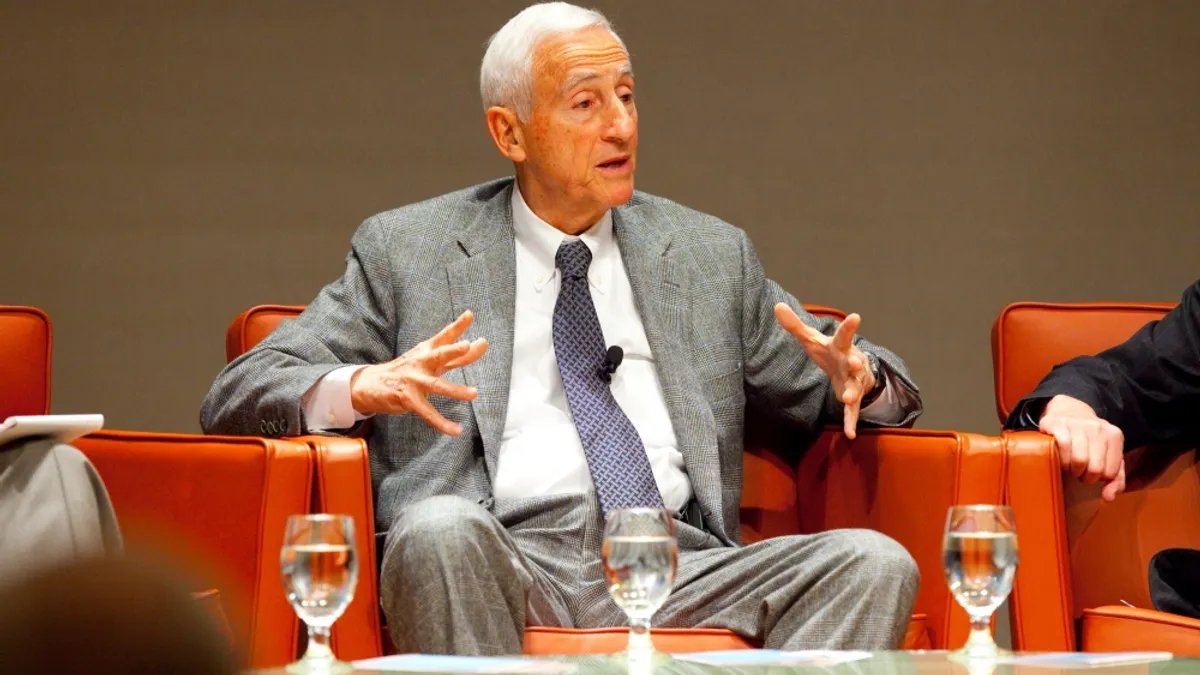

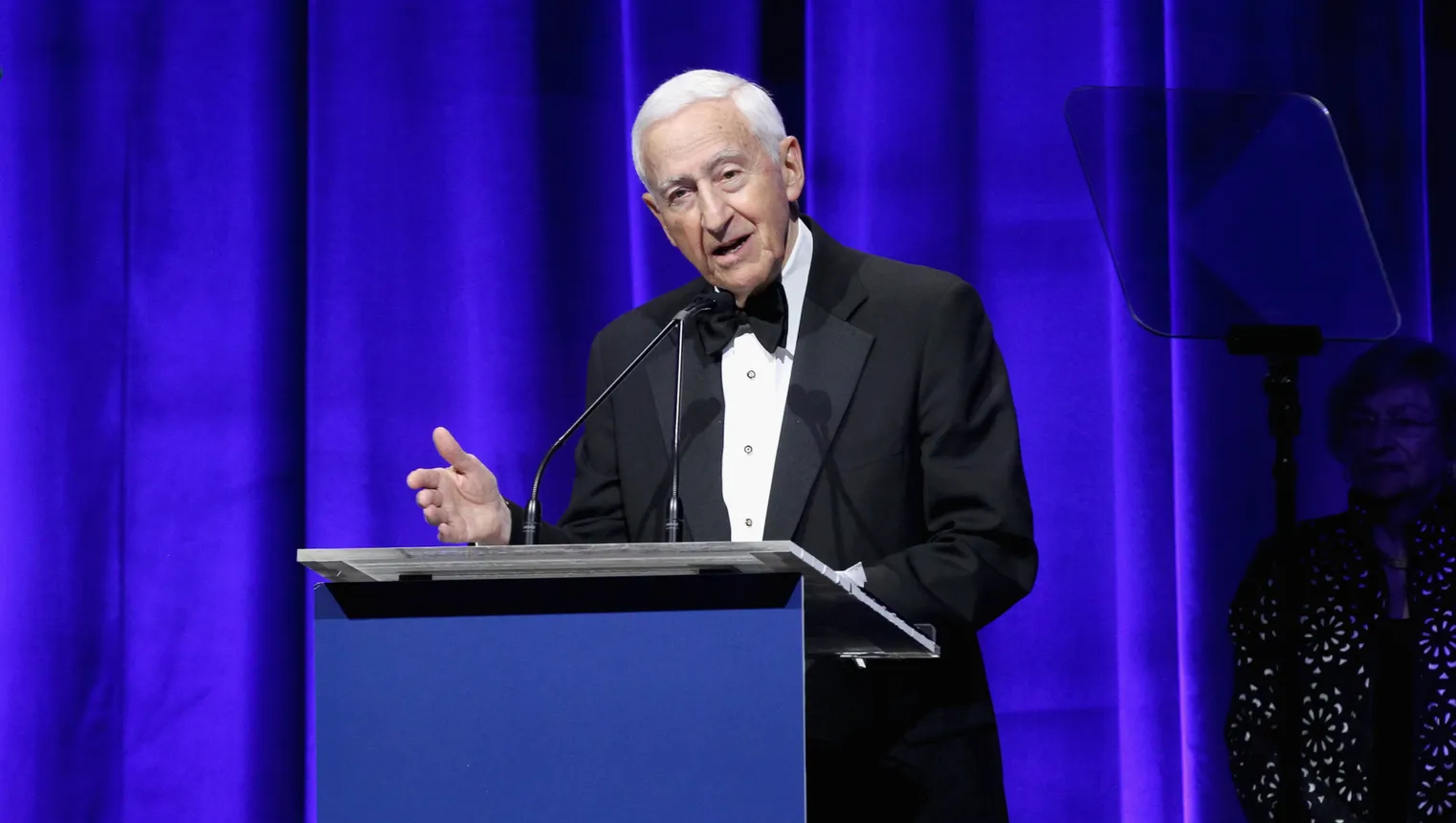

At 93, Dr. Roy Vagelos might finally be taking a break. The former Merck & Co. CEO plans to step down as chair of Regeneron’s board in June after almost 30 years of guiding the company from its beginnings as a fledgling biotech to becoming a global biopharma company.

His departure, however, will leave a footprint far past Regeneron’s door.

A child of Greek immigrants, Vagelos grew up in Rahway, New Jersey, in the shadows of the company he would one day lead. At his family’s luncheonette, Vagelos served sandwiches to the Merck biologists and chemists who made up the majority of customers.

Inheriting his father’s “doer” mindset, and mesmerized by those early scientific role models, Vagelos knew he was college-bound from a young age despite his parents’ lack of education, and eventually studied chemistry at UPenn, later earning his medical degree from Columbia University.

After two years serving as an Army doctor, he then jumped into the world of academia, working first as a senior surgeon at the NIH researching lipid metabolism, before founding Washington University in St. Louis’ groundbreaking Division of Biology and Biomedical Sciences. The division would become a model program for fusing undergraduate biology with medical curricula and now bears his name.

Ultimately, however, “the opportunity to influence the course of medicine” persuaded Vagelos in the mid-1970s to move from academia to pharma, and he never looked back. He joined Merck as senior vice president for research, rising 10 years later to become CEO and shepherding drugs including Timoptic, Primaxin, Vasotec, Mevacor, Zocor and Proscar to approval.

When, at 65, he was required to resign from his perch at Merck, Vagelos became chair of the then-stalling biotech Regeneron, helping transform it into a platform company with indications expanding beyond its original CNS portfolio.

Now a highly decorated leader recognized as a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Medicine and the American Philosophical Society, and by Prix Galien USA as the first recipient of its Pro Bono Humanum Award, also later renamed in his honor, Vagelos is an inspiring force in the life sciences.

While his scientific acumen and business savvy have marked Vagelos as a great leader, his compassion and people-first approach have made him a revered role model for so many in the industry — from former Merck CEO Ken Frazier to biotech entrepreneur Vijay Samant and Regeneron co-founder Dr. George Yancopoulos.

As he retires, lessons from the most pivotal moments of his career shed light on the principles of leadership.

Always look forward

Innovation is the bread and butter of the life sciences industry — and creating cutting-edge medications requires a forward-looking mindset. Vagelos put it this way: “Holding on to old ways in a new world will put a company out of business.”

Guided by his time in academia, he carried a penchant for research into pharma leadership. And it led him to “institutionalize” what was then a new model for drug discovery, now called “rational drug discovery,” based on identifying the structures of molecules and developing chemicals for distinct targets. The approach marshaled in the first FDA-approved statin to lower cholesterol and reduce risks of heart disease. It also provided the foundation for modern drug discovery.

In an interview with PharmaVoice, Vijay Samant, CEO of Xiconic Pharmaceuticals, credited Vagelos’ work with “single-handedly chang(ing) America’s health profile with regard to cholesterol.”

Keep your conviction

Vagelos is perhaps best known for his decision as CEO of Merck in the late-80s to make the company’s anti-parasite drug Ivermectin freely available in African and Central American countries experiencing widespread outbreaks of river blindness. At the time, 18 million people were going blind from eye infections associated with the tropical disease, and over 100 million people were at risk of contracting it.

But it was no easy feat to get the drug to market. It was discovered shortly after Vagelos joined Merck and, in an initial human study, was found to completely rid patients of the parasite. Despite these results, Vagelos told an interviewer in 2011 that WHO officials believed the results were “impossible” and brushed the researchers off, saying they had “screwed up the experiment.”

Nevertheless, Vagelos believed in the science and continued to push the drug forward.

“We turned on a huge development program because we knew we couldn’t have been wrong,” he said later.

The perseverance paid off and Merck developed a medication that could eliminate the disease with just one tablet a year. The only hitch was it was targeted to help poor populations unable to pay a hefty price tag for the drug. At a crossroads, and pressured by time and media coverage, Vagelos decided in two days and without consulting Merck’s board to provide the drug free of charge “to anyone, anywhere in the world, for as long as it was required.”

Today, that decision to choose people over profits has led to the declassification of river blindness as a public health threat in those regions.

Pay it forward

The importance of education was imparted on Vagelos from a young age and carried throughout his career, as evidenced by the millions of dollars he’s given to universities around the country.

But one moment during a college admissions interview, when a recruiter ended the conversation early after learning that Vagelos’ parents didn’t earn degrees in higher education, particularly stuck with him. He didn’t get into that school but was able to attend UPenn on a scholarship.

And over the last few decades, he’s repaid that scholarship many times over. For instance, in 2017 he and his wife Diana Vagelos donated $250 million to Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, with $150 million of that endowed to fund eliminating student loans for those who qualify for financial aid.

“We want P&S graduates to be able to do what they really love to do in their lives and in the medical profession, whether it’s in biomedical research or clinical care,” Vagelos said at the time of the donation. “We’ve been lucky enough to have the chance to make a difference and we want to be sure future Columbians will have the same opportunity.”

Through these philanthropic pursuits, along with his character and leadership, Vagelos has left a mark on future generations of life sciences leaders.