Welcome to today’s Biotech Spotlight, a series featuring companies creating breakthrough technologies and products. Today, we’re looking at Stoke Therapeutics, a biotech developing an RNA-based drug for the rare epileptic condition Dravet syndrome.

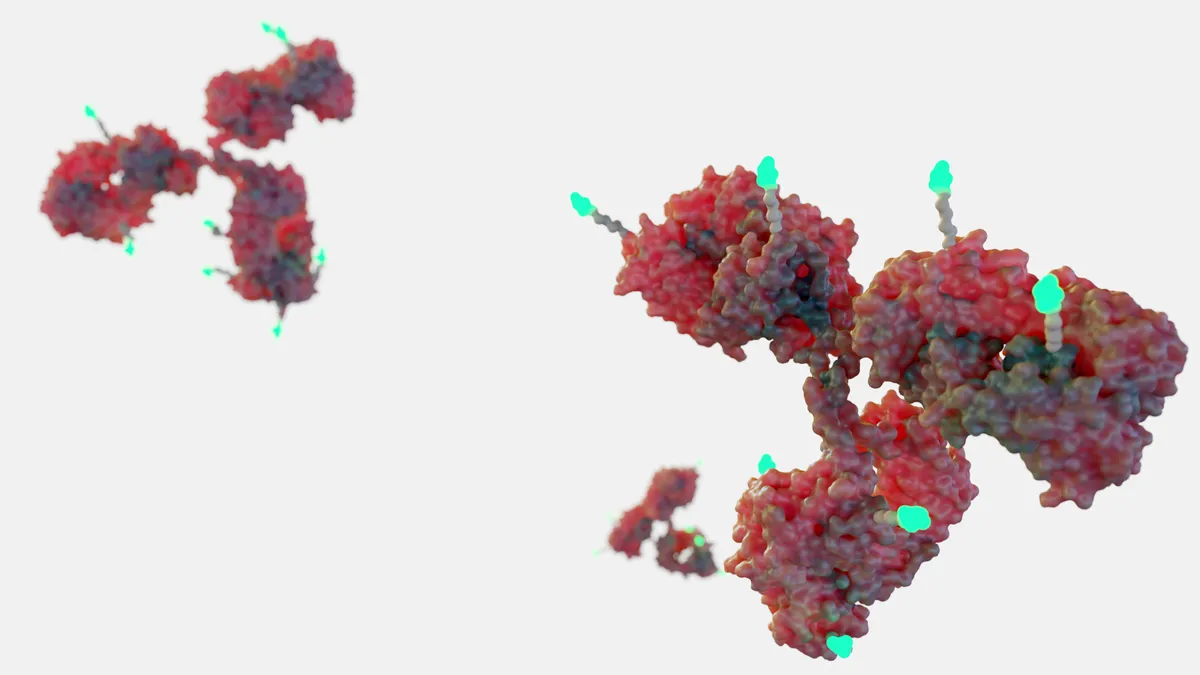

The 2020s are shaping up to be a golden age for RNA. From COVID-19 vaccines to rare disease treatments, RNA has become key to tackling many of biotech’s tough obstacles.

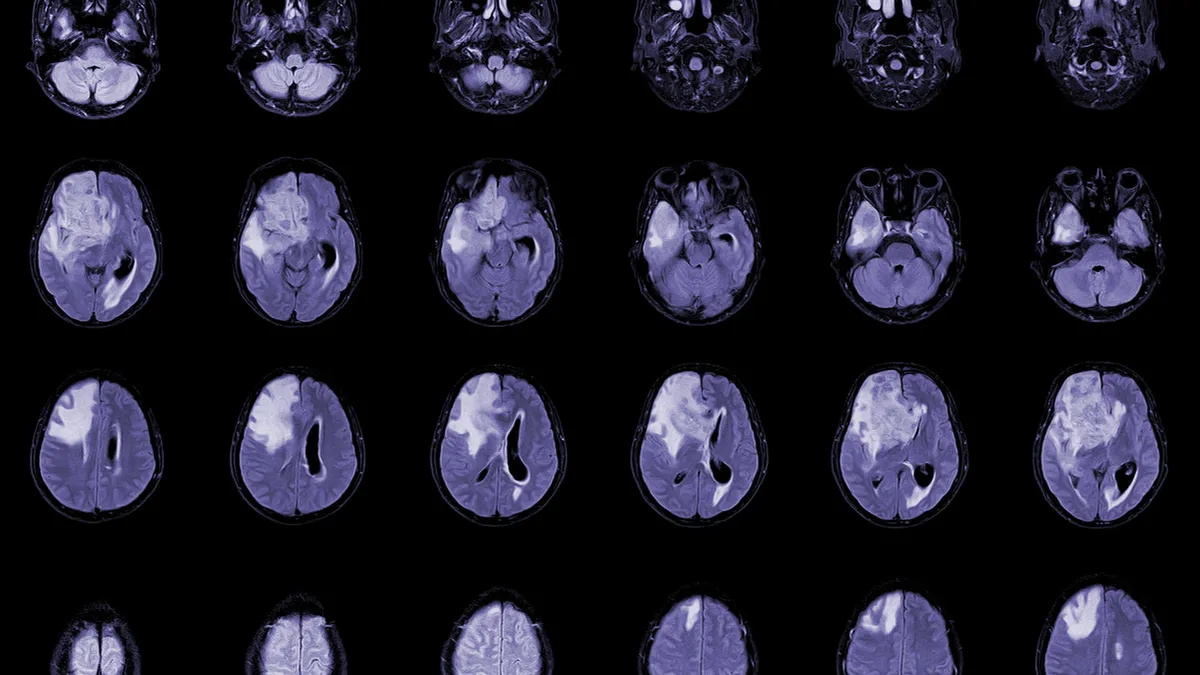

Stoke Therapeutics is bringing that RNA revolution to difficult neurological diseases that primarily affect children, including the severe form of epilepsy called Dravet syndrome, the genetic cause of which has only recently been understood, said Stoke CEO Dr. Ed Kaye.

Stoke is getting ready to bring its drug zorevunersen into a phase 3 trial after positive results earlier this year from a mid-stage study helped the company overcome previous safety issues. And Stoke’s drug candidates, which instruct a patient’s cells to create more of a certain protein rather than shutting down a gene, offer the opportunity to address diseases other biotechs in the field haven’t come as far in treating.

“What we’ve learned is that RNA medicines are very effective in up-regulating splicing, and what we try to do is fine-tune the amount of protein we need in those cells,” Kaye said. “We’re up-regulating some of the RNA splicing within the cells to increase the protein.”

With a few earlier-stage candidates in the pipeline, including a treatment for a rare genetic vision loss disease and others for neurological conditions, Stoke is working through the development cycle while also preparing for life beyond the finish line. The biotech in 2022 teamed up with Acadia Pharmaceuticals in a deal potentially worth more than $900 million to jointly develop the earlier-stage candidates.

"We’re not making widgets. We’re not making Coca-Cola. We’re making drugs that help people and can be life-saving in many cases."

Dr. Ed Kaye

CEO, Stoke Therapeutics

Kaye, who has held positions at Genzyme and Sarepta Therapeutics — where he led development of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy drug Exondys 51 — is embracing the innovation of RNA while returning to his roots as a pediatric neurologist.

Here, we spoke to Kaye about developing Stoke’s unique RNA approach, addressing the unmet needs in childhood epilepsy and overcoming challenges such as safety, manufacturing and patient access in the burgeoning field of RNA science.

This interview has been edited for brevity and style.

PHARMAVOICE: How does your RNA platform stand apart from others working with RNA?

ED KAYE: Most companies, if you think about Alnylam and some of the classic RNA ones, are primarily focused on down-regulating the gain and function of a protein. That’s just the opposite of what we’re trying to do, which is to increase a protein. And in many cases, we’re focused on going after dominant, genetic diseases where you’re missing 50% of the protein. So what we’re doing is using the cells, the endogenous equipment and machinery to up-regulate the protein back up to 100%. From an innovative standpoint, we’re doing something very different from what other companies are trying to do.

What are the unmet needs you’re addressing with zorevunersen in Dravet syndrome?

One of the things that has engendered a lot of interest in what we’re doing is that not only are we treating the seizures, but we’re seeing dramatic improvement in cognition and behavior. About 25 years ago, about half of all epilepsy was considered idiopathic, which means we didn’t really understand the biology. We didn’t understand why people had these seizures. Now we know that those seizures are caused by genetic defects, and every year we find more causes. So our idea was, rather than treating some of the symptoms like we’ve been doing for literally the last 170 years, now we have all these genes we know are the cause of epilepsy in many of these children and adults. If you asked me 10 years ago whether we would see improvements in these patients, I would have said no, it’s a done deal, a developmental abnormality. What has surprised even us is that we’re seeing improvements in cognition and behavior in patients who are 18 years of age or older.

You had to overcome safety issues in previous studies and a partial clinical hold in 2020. Can you talk about how you restore trust and continue after that?

With all therapies, there is a risk-benefit, whether it’s aspirin or anything else — if there’s a benefit, there’s always a potential risk. Very early in the development of this therapy, there were toxicities seen in juvenile monkeys with a temporary paralysis of the legs. What we found was that it probably happens with all antisense oligonucleotides being put into the spinal cord, with Spinraza as an example. What the FDA made us do was a slow escalation of dosing over time, and it took time to be able to safely increase the amount of drug to a point where it was working. Part of the challenge of drug development is that you never know what’s going to happen in humans until you do it. The FDA has taken us off the partial clinical hold, and we’ve now treated 81 patients with a very good safety profile.

With so many genetic medicines, we’re seeing the science advancing very far, but then the problems seem to happen around issues like manufacturing and patient access. What conversations do you have at this point around those aspects of the process?

What we’re doing now is to make sure we’re already at a commercial-grade manufacturing process, and it’s pretty straightforward. It’s not as difficult as, say, gene therapy. We have the manufacturing process down, and we have adequate supply for the entire phase 3 study. We’re in the process now of making sure we’ll have drug supply for commercialization through vendors both for drug product and drug substance. We’re a little ahead of the curve in that regard — I learned from my time at Genzyme what happens when you don’t have adequate supply. It’s a terrible thing for patients.

Then we’re also focused on making sure patients can get access to our drug, and in rare diseases, the most important thing is getting reimbursement. Most of the physicians who will be using it understand the drug quite well. The problem is, do the payers understand how well this drug works and why it’s important? That process has already started as well. We’ve already hired our head of commercial, Jason Hoitt, who I worked with very closely at Sarepta, and we’re putting in place all of those mechanisms. This is years before we’re going to launch, because we’re trying to avoid some of those pitfalls that many companies get into.

With your experience in the industry over time, how do you keep your eye on the next wave of innovation?

What’s exciting about biotech is you’re dealing with really smart people with really interesting science, and at the end of the day you’re trying to apply that science to make patients’ lives better. We’re not making widgets. We’re not making Coca-Cola. We’re making drugs that help people and can be life-saving in many cases. The problem is that most of the things that start in biotech fail. It’s very risky. It’s not for the faint of heart, but when you get something that changes a patient’s life, it’s an accomplishment that stays with people forever. Sometimes it’s scary to be the first, but it’s also exciting to think about developing a therapy for the first time that’s never been done before.