If an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, then pharmas face an existential quandary: In the business of selling medicines that treat disease, what happens when what's best for patients is avoiding disease altogether?

Although financial incentives for payers, providers and drugmakers tend to skew toward treatment, many of these entities do actually intend to make prevention a priority for the patient and the healthcare system as a whole.

"Patients who are in value-based care models benefit from much stronger preventative care management, as you would imagine," Maria Whitman, global head of the management consulting firm ZS's pharmaceutical and biotech practice, says. "Breast cancer screening rates go up, colorectal screening rates go up, cancer screenings, everything you can imagine — so that's a win-win, but it's very hard to execute."

Value-based care is a model that ties payment not only to the treatment a patient receives but also to the quality of care, the experience of the patient and the overall outcomes of the patient's health. To make that model work, pharmas need to provide "more than medicine," Whitman says.

"We started out in a world where pharma was focused on the benefits of a product — we've moved now to a focus on driving a better experience for the customer in utilizing the product," Whitman says. "The next thing — whether they like it or not, and I do think many of them are proactively going there — is going to an outcomes-focused world."

Some of the ways drugmakers can head in that direction are through real-world evidence programs, awareness campaigns, cross-industry partnerships, prediction analytics and increased screening.

"At the end of the day, prevention is a win for patients, their families and society."

Maria Whitman

ZS head of pharmaceutical and biotech practice

In disease prevention, the patient is key, Whitman says. Helping patients become aware of prevention opportunities can be a challenge, and screening for disease is where that starts.

"A big part of the system is the patients and patient awareness, which for screenings is very low in general," Whitman says. "In my family, when my stepdaughter turned 12, I happen to know there is a cervical cancer vaccine, but most patients don't even realize that, and if your doctor is not telling you because they're dealing with acute issues in the moment, then you never get there."

Countries like Australia have taken it to heart — a mission to be the first nation to achieve cervical cancer elimination through HPV vaccination and screening interventions have brought incidence rates down 41% in women 20 to 24 years old.

Although traditionally pharma hasn’t necessarily been in the business of prevention, Whitman says there are plenty of opportunities for that model to change.

Prevention first, treatment second

To move toward a preventative model, Whitman says that pharma companies need to recognize that medicine can only go so far in determining the overall health of a population. Whitman says about 80% of health is environmental and behavioral, and efforts to change those factors would go a long way.

"The needle is moving on how we're defining success in disease," Whitman says, using diabetes as an example. For 30 years, the goal was to reduce A1C, which is a measurement of blood sugar, she says — now, that urgency has shifted to reversing pre-diabetes before the disease fully forms.

"When the goal shifts in terms of clinical meaningfulness, and that's where governments are heading, and that's where health is heading, then pharma has to go along with it," Whitman says.

The traditional treatment model has been reactionary — and profitable — as drugmakers sell a volume of their product based on the number of patients with that condition. And it can be difficult to tear away from a dynamic that has been so successful.

"This is where we're going to see a bifurcation in the future — pharmas are saying, ‘I can stay a medicines provider because we're still going to have a lot of people who need to reduce A1C, and I can keep trying for discovery and I can be profitable, and I can live there,’" Whitman says.

But there is another option on the table, and that is where medicine is heading.

"The other option is pharmas can be more than medicine," Whitman says. "So the question is, am I going to stay a medicines provider? Or am I going to expand my breadth to think about playing in that earlier space and still make money from it without being completely altruistic."

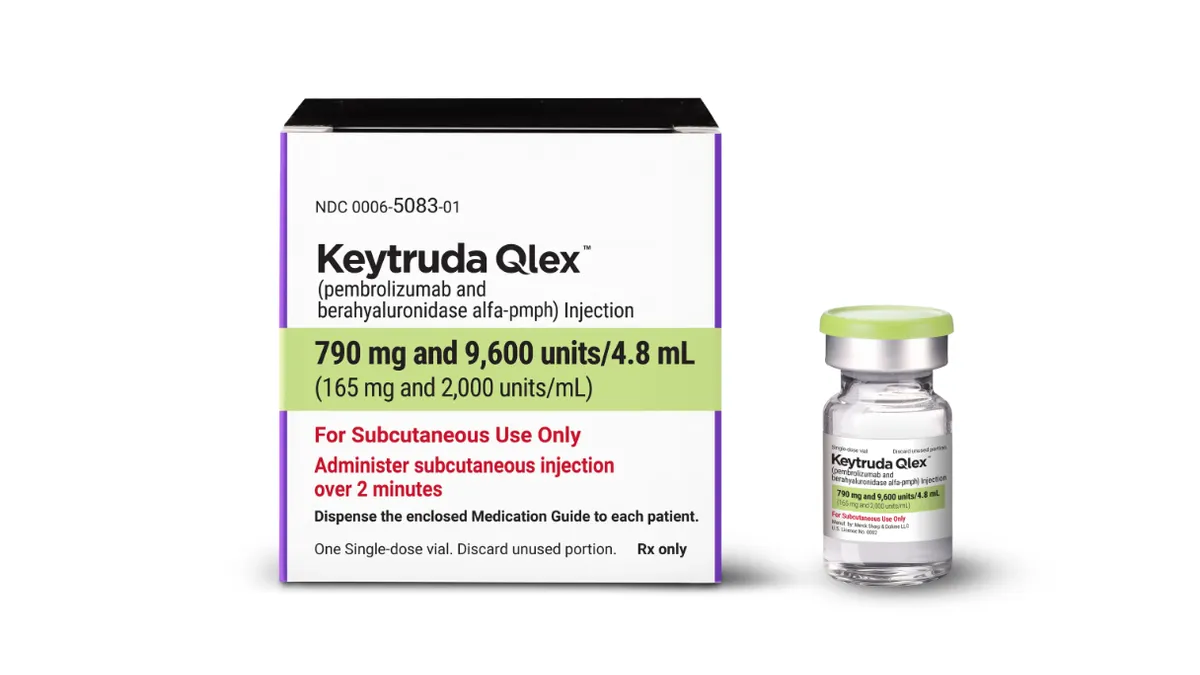

Payment models for cutting-edge technology like gene and cell therapies have brought about a tide change in how the industry even thinks about its role. Million-dollar cures like Novartis's Zolgensma, a gene therapy approved to treat the rare childhood disease spinal muscular atrophy, made outcome-based contracts a priority for payers — the treatment would be covered based on how a patient responds, not on whether or not they received the therapy.

"There are a lot of outcomes contracts out there, and there are a couple of things that have to change in order for them to truly become meaningful," Whitman says.

With gene and cell therapies, the industry needs a better sense of what durability expectations should be. A first generation of outcomes-based contracts came with standards by which to judge whether a treatment has worked or not, and Whitman says these can be made more meaningful with better exploration during the clinical trial phase.

"What is the expectation of response rate that makes for an outcome that makes a high-cost one-time therapy?" Whitman asks. "So the challenge hasn't been a lack of willingness to come to the table but rather an operational ability to execute it."

More than words

When drugmakers say they are putting patients first, it can seem like lip service made for flattering press releases and reputational security — but many of the biggest companies in the world are indeed putting their money where their mouth is.

Real-world evidence, collected from patients using electronic medical records and insurance claims, can help companies learn more about prevention. Pharma giant Eli Lilly has put it to use in a study called Triumph evaluating the preventative effect of their migraine treatment Emgality. Similarly, Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer have demonstrated the real-world use of their drug Eliquis in preventing heart attack and stroke.

"What I'm seeing now is a greater investment in the capability of real-world evidence on the part of the individual pharma companies," Whitman says. "And there's definitely been a shift to a more thorough integrated evidence plan across the board so that we can better predict what we would base that on, and then we'll have more data to show the value and to feed back into the next generation of development."

And as in many aspects of the healthcare industry, partnerships have furthered the cause of prevention by connecting big pharma companies with smaller players focused on patient wellness.

J&J's innovation center JLABS has taken the idea a step further in creating the World Without Disease Quickfire challenge, offering funding to small companies working to develop solutions to global health and wellness. Whitman called the program a "mini Warp Speed," referring to the public-private drive to create COVID-19 vaccines and treatments.

In diabetes care, Novo Nordisk sponsors the public-private partnership Cities Changing Diabetes, which launched in Houston in 2014 and is now operating in cities worldwide to fight obesity and identify areas and populations at greatest risk with a focus on diabetes prevention.

"At the end of the day, prevention is a win for patients, their families and society," Whitman says. "The players in the ecosystem recognize that, and there is increasing commitment and opportunity — fueled by innovation and even the pandemic — to get there."