It’s not a done deal. But so far, all indications point to the probability of Veru, a small biotech, winning the latest Emergency Use Authorization from the FDA for a COVID-19 treatment. And if all goes well, the approval would be the first of its kind for a company of its size — potentially catapulting Veru from relative obscurity into a blockbuster drugmaker.

Here’s how it happened.

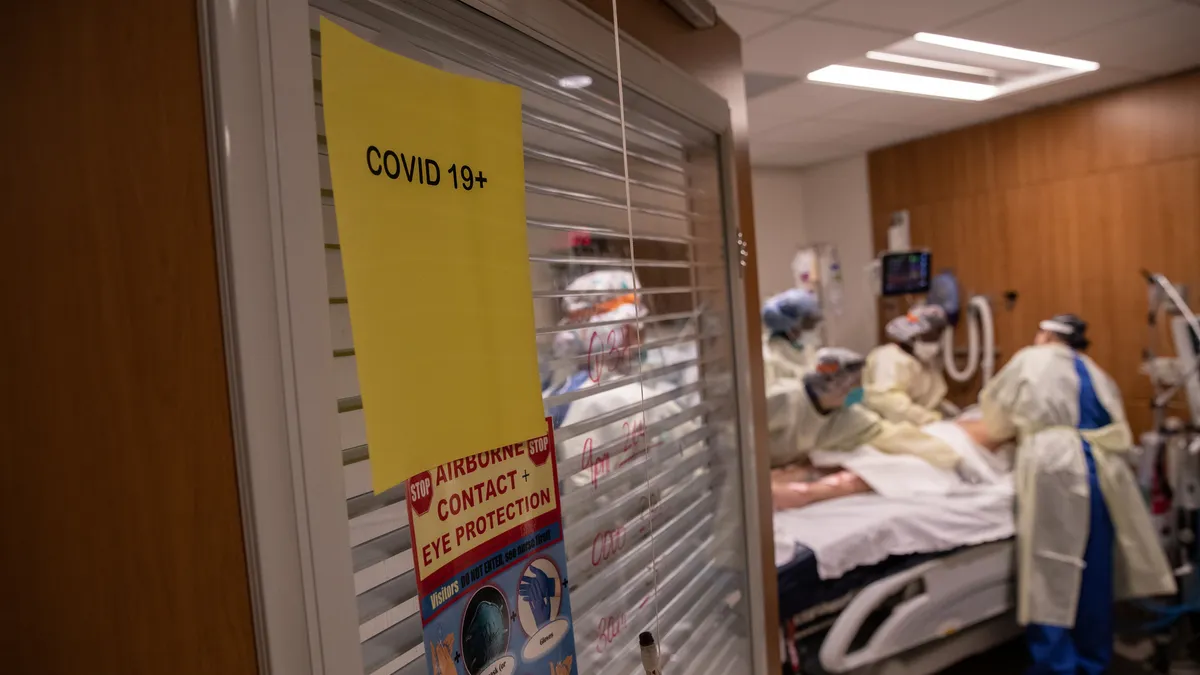

The company announced in April that it was halting a late-stage trial for sabizabulin, an antiviral and anti-inflammatory treatment in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, because the drug was so successful in reducing deaths, it would not have been ethical to continue giving other patients a placebo.

On May 10, Veru was then granted a pre-EUA meeting with the FDA to discuss filing for the approval. According to Veru’s CEO, Mitchell Steiner, the tone of the meeting was unlike others he’s had with the agency.

“They’ve seen the data. The safety is there, the efficacy is there,” he explains. “So this was more like they were saying ‘Tell us about your drug supply because we have to get this going.’ It was very process-oriented.”

The reason for the rush is that although vaccines have made an enormous impact on the fight against COVID-19, and other therapies have been shown to reduce symptoms or speed recovery, the death rate for hospitalized patients has remained stubbornly high. But in the trial of severely ill patients with COVID-19 at high risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sabizabulin reduced the chance of death to about 20%, compared to 45% on a placebo.

And of course, the pandemic hasn’t been “behaving,” Steiner notes. Despite the many mitigation efforts, COVID-19 has continued to mutate and spread — presenting an ongoing challenge made all the more apparent recently when the U.S. passed the grim milestone of 1 million COVID-related deaths.

“If our drug would have been available at the start of the pandemic, 500,000 patients would be home right now,” Steiner says.

Veru plans to submit its materials for the EUA by the end of this quarter and expects to hear back from the FDA within two months of submission.

Now, Veru is hustling to quickly scale up for widespread distribution.

The pressure’s on

This wouldn’t be the first commercialized product in Veru’s portfolio. Although Veru has clinical-stage oncology drugs in development — including sabizabulin, which is being studied in patients with certain forms of prostate and breast cancer — the company also has commercialized products in its sexual health division. But this will be an acceleration on a whole new level for the small pharma.

“Most companies get 18 months to launch a new product,” Steiner notes. “We’re only going to get a few months.”

Veru’s API manufacturer is based in Italy but has a plant in Ohio, which Steiner says will create needed redundancy in its supply. It’s also working with a contract company, CoreRX, for drug formulation. At the moment, Steiner says the contractors will be able to handle its current supply plans — Veru has enough doses for 57,000 patients ready, will make enough for another 100,000 patients in August, and then ramp up to producing a 250,000-patient supply in September.

"People can’t believe that this small company is pulling this off. So the next big step is showing people that we’re real. We’ve landed."

Mitchell Steiner

CEO, Veru

“We’ll stay at 250,000 a month from there on out. So every four months, we can treat 1 million patients,” he says, noting that they may have to add another manufacturing facility into the mix to maintain that goal.

If Veru scores the FDA approval, the company will concentrate on the U.S. market first. Steiner points out that distributing in hospitals will take some of the complexity out of the drug’s rollout.

“The hospital distribution is much tighter and easier than pharmacies,” he says.

If other countries follow the FDA’s lead, Veru also has plans to go global. As Steiner notes, the small molecule drug could be a particularly useful defense against the illness in remote parts of the world.

“[Sabizabulin] is a pill. It doesn’t require cold storage,” he says. “So you can put it in backpacks for distribution.”

This week, the company also announced that it has hired Joel Batten, the former head of the Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Franchise at Sobi North America, as Veru’s executive vice president and head of its U.S. Infectious Disease Franchise.

In a statement, the company said that Batten will help “build on the momentum of our positive phase 3 sabizabulin for COVID-19 trial, our planned EUA submission, and the transition to delivering sabizabulin, if EUA is granted, to hospitalized COVID-19 patients at high risk for ARDS.”

A potential blockbuster

Just how big could sales be for Veru’s sabizabulin? Based on the current hospitalization rate and the price charged by Gilead for remdesivir, an intravenous antiviral that’s been shown to accelerate recovery from COVID-19 in moderate to severe cases, some analysts predict that Veru could see $250 million in annual sales. But if the company prices sabizabulin higher, the drug could surpass blockbuster levels.

At the moment, Veru says it is still determining what the price will be for a course of sabizabulin. For now, Mitchell also draws a parallel between sabizabulin and remdesivir when forecasting sales.

“If you look at remdesivir as a benchmarck … last year they had $5.6 billion in revenue,” Steiner says. “But I think we’re better because [our drug] actually has a reduction in the death rate.”

Although Veru arrived on the public’s radar after the trial results were announced in April, the journey started two years ago when the company began discussions with the U.S. Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) about sabizabulin’s promise as a COVID treatment. Of course, at the time, hundreds of potential candidates were being rushed into studies.

“It started out like the beginning of a 5K race, when you can’t even run because there’s all these people. And then, you look around at the end, and there’s no one else there,” Steiner says. “We’re like that turtle in the race. We stayed, and we worked, and we kept at it.”

As the company preps for its EUA filing and then awaits the final verdict, Steiner is already mulling the broader potential of sabizabulin, and the company is in the late stages of planning studies for the drug against influenza, RSV and more.

“We accept 60,000 deaths from influenza a year, but we don’t have to anymore,” he says.

Now that the experience has kicked into whirlwind-mode and Wall Street has taken notice of Veru’s potential EUA, Steiner says the company is also working to prove it can pull this off.

“It’s been a blur. We’ve been going through this for five weeks and I’ve been on the phone every 20 minutes,” he explains. “Our stock is going all over the place because people can’t believe that this small company is pulling this off. So the next big step is showing people that we’re real. We’ve landed.”

Editor's note: Learn more about Veru’s strategy to develop potential blockbuster oncology drugs while avoiding biotech’s “valley of death” in our profile of the company published in February.