Within the pharmaceutical industry, a multibillion-dollar race is underway to top Novo Nordisk’s and Eli Lilly’s in-demand obesity drugs.

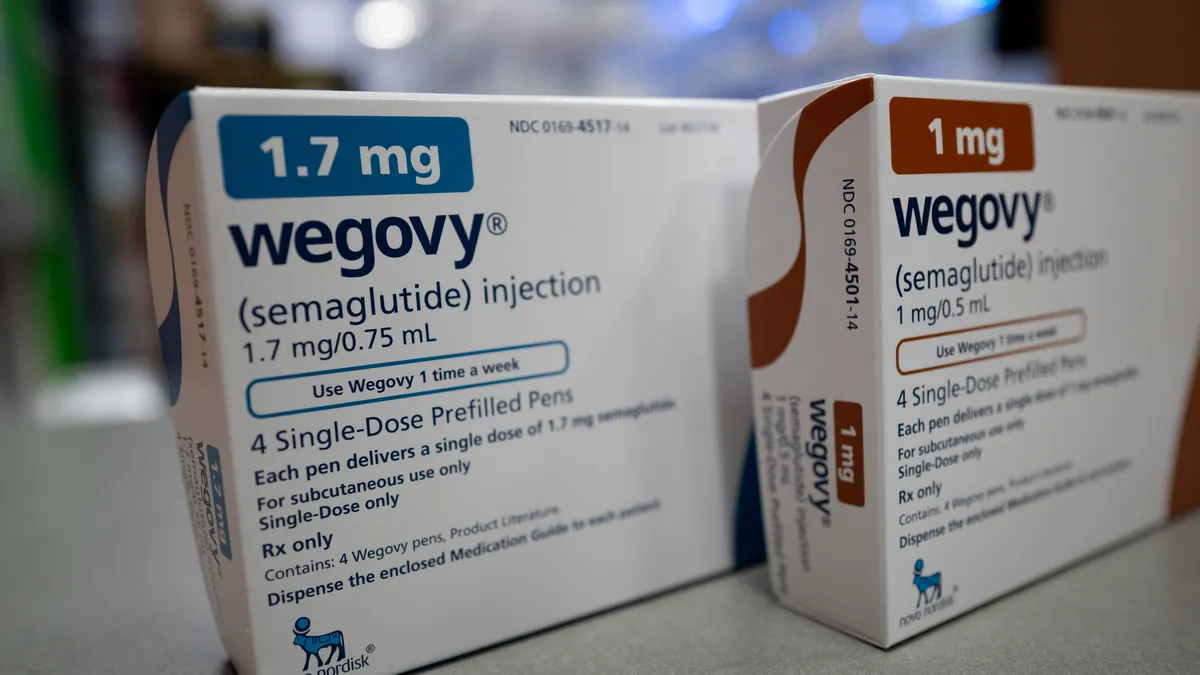

Dozens of companies, large and small, have set out to test experimental medicines they claim could be more potent, convenient or have fewer side effects than Novo’s Wegovy and Lilly’s Zepbound. But those two companies are already hard at work with successors of their own.

The next six months figure to be an important preview. Data are expected for a number of drugs that are already, or are shaping up to be, contenders in this high-stakes competition. The readouts will be closely watched, as they will set expectations for how the obesity drug market — currently a duopoly between Lilly and Novo — will look in the future. Here’s what to expect:

Zepbound versus Wegovy

Head-to-head trials always carry high risk. Any company that sponsors one is doing so with the knowledge testing could reveal its drug is equivalent to a competitor or, worse, less effective.

With Zepbound, Eli Lilly appears to believe it’s a risk worth taking. In a trial called SURMOUNT-5, Lilly enrolled 700 people in an attempt to prove Zepbound is better than Wegovy at reducing the body mass of people with obesity or who are overweight, and have another weight-related complication like heart disease or high blood pressure.

It expects to have results by the end of the year, and the findings could impact physician and patient perception of which drug offers greater weight loss benefits..

So far, Zepbound has seemed superior, as testing showed treatment helped people with obesity lose up to 21% of their body weight. The comparative figure for Wegovy was 16% in the phase 3 trials Novo used to gain Food and Drug Administration approval. Based on this, Leerink Partners analyst David Risinger expects Zepbound to show a statistically significant advantage in the head-to-head trial.

A resoundingly positive outcome could help push Lilly past $1 trillion in market valuation, a milestone that would be a first among pharmaceutical firms. Lilly is currently worth nearly $900 billion.

But Lilly has yet to prove Zepbound can prevent cardiovascular complications in people with obesity or who are overweight and already have heart disease, as Novo has with Wegovy. That study result helped Novo gain limited Medicare coverage for people with existing heart disease. Lilly has an outcomes trial called SURPASS-CVOT underway, but doesn’t expect to have data until next year.

Novo’s ‘dual agonist’

Wegovy works by stimulating a metabolic hormone called GLP-1, while Zepbound targets GLP-1 and a second one called GIP. The biology behind the dueling approaches is still being sorted, but Zepbound’s “dual agonism” has set a model for others to follow, including Novo.

The Danish company is now in late-stage testing with a dual-acting experimental drug it calls cagrisema. The drug combines semaglutide, the active ingredient in Wegovy, with another compound that mimics a metabolic hormone called amylin.

Cagrisema’s phase 3 trial, called REDEFINE1, is due to wrap up and generate data in the fourth quarter. The results could help Novo fight off Lilly’s commercial challenge should SURMOUNT-5 favor Zepbound over Wegovy.

REDEFINE1 tests cagrisema against a placebo and Wegovy, measuring weight loss over 68 weeks in about 3,400 people. Cagrisema’s performance against Wegovy should give analysts a sense of how well it might also measure up against Zepbound, once the SURMOUNT-5 data are available.

Novo is also testing cagrisema directly against Zepbound, but that trial isn’t due to generate data for another year.

Amgen’s contender

Amgen isn’t known for cardiometabolic drugs, but it has one, called maridebart cafraglutide or maritide, that’s among the most closely-watched obesity medicines not owned by either Lilly or Novo.

Maritide targets the same two gut hormones, GLP-1 and GIP, that Zepbound does. But, somewhat controversially, it is designed to inhibit rather than stimulate GIP. It is also a monthly shot, compared with the weekly injections used for Wegovy and Zepbound.

Phase 2 results for maritide are due by the end of the year. Enthusiasm for the experimental drug’s potential has driven Amgen’s shares higher this year — sometimes dramatically so. Phase 1 data Amgen disclosed in February suggested it might drive the most weight loss among tested drugs over 12 weeks, according to Stifel analysts.

The phase 2 trial enrolled nearly 600 people with obesity, some of whom also have diabetes, and randomized them to receive one of several doses of maritide or a placebo. Researchers will measure weight loss over 52 weeks.

An obesity pill

Novo has advanced an oral version of Wegovy and Lilly has pushed its pill oforglipron into phase 3 trials. But there are many rivals staking their competitive future on the idea that people with obesity will prefer a pill over a shot. Roche is one such company, having acquired Carmot Therapeutics for $2.7 billion in late 2023 to gain access to three obesity drugs.

A phase 1 dosing trial of the GLP-1 pill CT-996 is due to wrap up by November, which will give Roche and its investors an idea of the drug’s biological activity, safety and weight loss. Roche already reported data from earlier stages of the trial, which tested single and increasing doses in trial volunteers who are overweight or have obesity. The third part will test the pill in 60 people who have diabetes in addition to obesity or being overweight.

Roche has already said CT-996 “will advance into phase 2 clinical development” based on the phase 1 data. It’s already touting the drug’s best-in-class potential, although phase 2 data will be a better test of that claim. Others are already in phase 2, including Pfizer with its drug danuglipron and Structure Therapeutics with GSBR-1290. They could soon be joined by Terns Pharmaceuticals’ TERN-601 and Viking Therapeutics’ oral version of VK2735.

Preserving muscle mass

The rapid weight loss stimulated by GLP-1 agonists melts away muscle as well as fat. That worries some experts, who note how people who discontinue treatment tend to regain weight in the form of fat. Muscle cells also have a higher resting metabolic rate, which results in higher caloric burn.

In response, some drugmakers are exploring ways to preserve lean muscle mass. An early test could come in the form of results for Veru’s enobosarm, a type of drug that stimulates muscle-building hormones. Previously sold under the name Ostarine, it has been tested clinically in people with cancer whose muscles have shrunk, as well as those with muscular dystrophy.

In obesity, a phase 2 test of enobosarm together with Wegovy is underway in people 60 and over who are overweight or have obesity and have lost muscle mass. The trial will measure how much trial volunteers’ muscle mass changes over 16 weeks, and will compare results in people who receive the two drugs to those who were given only Wegovy. Another endpoint will assess physical function by evaluating how participants climb stairs.

Veru expects results by the end of the year. The data could help analysts parse how important lean mass might be in future obesity treatment.

A new drug target

Outside of targeting GLP-1, GIP, amylin and other gut hormones, there are a range of other treatment approaches under evaluation. One involves blocking a cannabinoid receptor called CB1 that is known for regulating an appetite-modulating hormone called leptin. CB1 is known to have effects on other biological functions such as inflammation, too.

So far, there’s been at least one disappointing data point on CB1 inhibition. A mid-stage trial for a Novo drug called monlunabant didn’t meet expectations for weight loss, leading Novo to state that “further work is needed to determine the optimal dosing.”

The next shot for CB1 may be Skye Bioscience’s nimacimab, which is due to have interim phase 2 results by mid-2025. The trial, called CBEYOND, tests nimacimab against placebo, as well as a combination of Wegovy and nimacimab against Wegovy alone. The study will measure weight loss over 26 weeks. Enrolling 120 volunteers, the study should be large enough to detect at least an 8% difference between the experimental drug and placebo, according to the trial’s plan.

Skye shares fell by more than 40% the same day Novo reported its data for monlunabant.