For people whose trust in the pharmaceutical industry has been splintered by the opioid epidemic, hearing that a company is developing a novel narcotic with the promise of high pain control and a lower risk of dependence might raise alarm bells.

That’s why Tris Pharma, a privately held, commercial-stage biopharma company, believes rebuilding trust is a critical part of the strategy for bringing its novel pain treatment, cebranopadol, to market.

“That is going to be our biggest challenge,” said Ketan Mehta, Tris Pharma’s founder and CEO. “I think trust, especially in the pain management, has been broken, and that is understandable.”

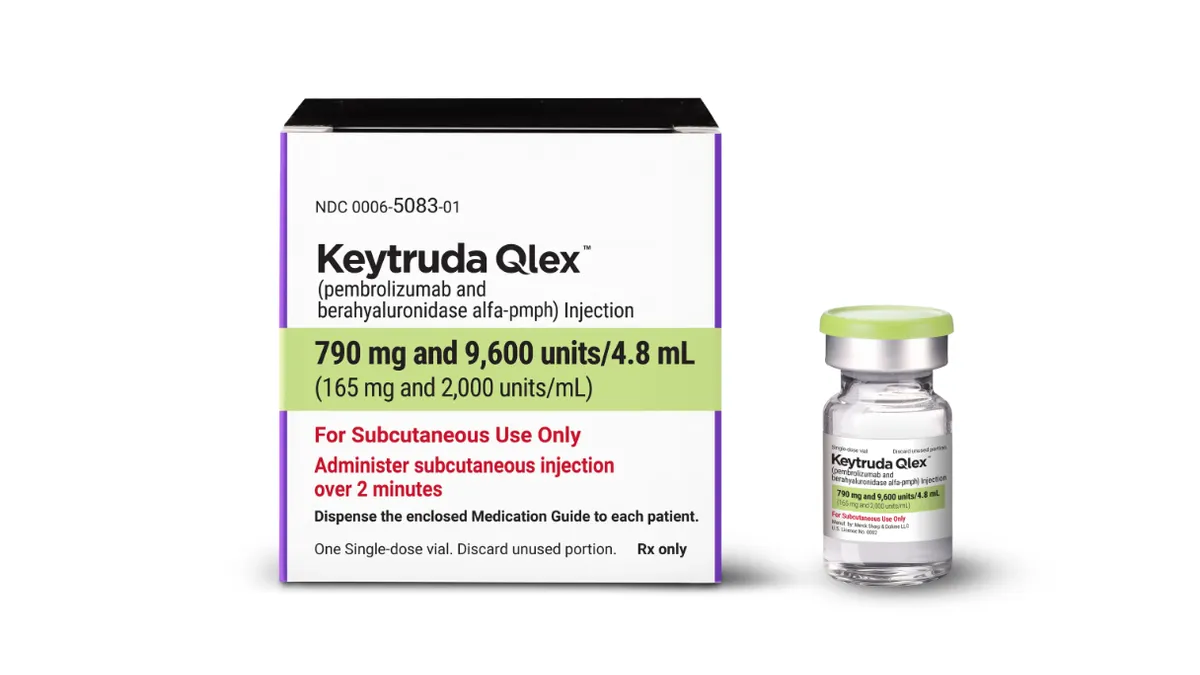

In December, Tris released positive topline clinical data from its oral human abuse potential study, which suggested that cebranopadol has a lower potential for abuse compared to both tramadol and oxycodone. The FDA has granted cebranopadol fast-track status.

Although cebranopadol acts on the mu opioid receptor, Tris Pharma doesn’t refer to the drug as a traditional opioid. Not only does the word come with baggage, but Mehta said cebranopadol is “a new kind of pain reliever” that is more than just an opioid.

Instead, cebranopadol is a dual nociceptin/orphanin FQ peptide (NOP) receptor and μ-opioid peptide (MOP) receptor agonist. Because it targets both the NOP and MOP receptors, the drug is in clinical trials to evaluate its ability to produce similar pain-relieving effects as traditional opioids but with significantly reduced side effects such as euphoria, respiratory depression and physical dependence.

In fact, “NOP agonists (including cebranopadol) can be used to treat substance use disorders,” according to research published in the journal Molecules.

“You are getting the best of both,” Mehta said. “I think that’s game-changing data that we will be presenting with (the) FDA.”

Why now?

It might seem like a tenuous time to launch a new pain medication that targets opioid receptors. Although 2020 saw the overall national opioid dispensing rate fall to its lowest in 15 years, according to the CDC, opioid overdose rates have not slowed.

In fact, NIH data shows that overdose deaths involving opioids shot up from 21,089 in 2010 to 47,600 in 2017, and then spiked to 80,411 in 2021.

In recent years, opioid overdose deaths have largely shifted from prescription narcotics to drugs sold on the street that include fentanyl, but pharma’s role in the epidemic continues to hang over the industry and is still playing out in courts around the country. Most recently, a federal appeals court in New York allowed a bankruptcy settlement for Purdue Pharma — the company that sold Oxycontin — that will shield its owners, the Sackler family, from future lawsuits. Although Purdue has agreed to pay billions of dollars to victims, survivors and states for its role in the opioid epidemic, millions of Americans are still gripped by opioid addiction.

“It just makes you humbled by people who’ve been taken advantage of by the industry and how we have lost trust,” Mehta said. “It makes us all look bad, unfortunately.”

So, why is Tris attempting to enter the market now?

“The trend of prescribing opioids is going down and down, but the need to treat pain remains strong,” Mehta said.

In particular, Mehta pointed to an aging population — in just seven years, all Baby Boomers will be 65 or older — and said that there are about 50 million patients in the U.S. with chronic pain.

“The old pain relievers like NSAIDs … and others, they are just not enough,” he said.

"The trend of prescribing opioids is going down and down, but the need to treat pain remains strong."

Ketan Mehta

CEO, founder, Tris Pharma

Despite that need, “nobody’s really investing in pain right now,” Mehta said. “If you look at the Big Pharma pipeline, nobody’s investing. And that’s where I think … there’s an opportunity for a small or mid-sized company like ours to really fill that gap.”

Marrying experience with risk taking

Mehta came to the U.S. from India to earn his master’s degree in pharmaceutical sciences over three decades ago and never left. Instead, he found a home, a place where he naturally fits.

“I just loved the country. The openness, how you’re allowed to ask questions,” he said. “Nobody discourages you to ask questions.”

He said he’s always been a curious “troublemaker” who needed to know the “why” behind everything, which has suited his career in pharma. While he worked in various research and marketing roles at different companies throughout his career and founded Tris in 2000, Mehta’s first job after school was in Eastman Kodak’s pharmaceutical division.

Since then, the company has gone through a number of evolutions and no longer exists in the form that it did when Mehta worked there. Despite having invented the first digital camera, it struggled to keep up with the switch from film to digital photography and got left behind. Now, Mehta keeps a bronze camera on a shelf in his office as a reminder and a lesson.

“It tells me you have to innovate,” he said. “Otherwise the world is really, really harsh, and you could become very quickly obsolete.”

Innovating in pharma is about taking smart risks and focusing on patients, and Tris is already doing both, Mehta said. For instance, its LiquiXR drug delivery technology led to the development of multiple first-in-category products in ADHD.

Now, although Tris has other products in its pipeline, including candidates for ADHD in adults and children, narcolepsy and spasticity, Mehta said he is “pretty much betting the company” on cebranopadol as it ramps up for a phase 3 trial later this year.

The company has a lot of work ahead to rebuild and earn trust with regulators and prescribers, but Mehta said he plans to let the data do the talking with “a degree of transparency that (people) are not used to.”

Tris is even conducting an additional respiratory depression study beyond what’s needed for approval in an attempt to create “hard-core data” that show the drug’s real promise.

“We will have to report the data first and make the claims later,” Mehta said. “You just have to be very open and transparent and let the experts make their own decisions, rather than telling them what to think about it.”