Michael Giles founded Sonara Health “out of frustration.”

Giles was doing a residency rotation at a methadone clinic, where “all of the new patients [he] had were coming to the clinic six days a week for 90 days, waiting in line to take a single dose of medication,” he said.

If they missed their appointments — and therefore, their methadone dose — it was because of another commitment, like taking care of young children or going to work, he said.

Yet, as Giles stood witness to the growing national problem of opioid addiction every day, on the news he saw Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson going to space and talk of reusable rockets.

“I was like, why are we solving this problem when we have this terrible opioid [epidemic] with record high overdose and death rates?” Giles, who is now Sonara’s CEO, said. “So really the company was formed out of frustration with the goal to help solve this problem.”

The result was Sonara Health, a Mark Cuban-backed company founded in 2020 that uses an inexpensive, specially engineered drug label along with a web app to allow patients to administer their methadone themselves at home with digital supervision instead of at daily, in-person clinic visit.

While the repercussions of the opioid epidemic continue to play out in court — last month, a federal judge ordered CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart to pay $650.5 million to two Ohio counties for their part in perpetuating it — the addition of fentanyl is making it especially hard to combat.

Overdoses from street versions of synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl, are rising and now responsible for the vast majority of both opioid-related and all drug overdose deaths. Last month, DEA administrator Anne Milgram called fentanyl “the single deadliest drug threat our nation has ever encountered.”

Meanwhile, methadone remains one of the most effective treatments for opioid addiction, especially for fentanyl, Giles said. It’s also highly addictive and prone to misuse and diversion, making clinicians extremely wary about giving patients doses of it to take themselves at home, even though the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration relaxed its guidance on at-home dosing during the COVID-19 public health emergency.

As a result, most patients must visit a clinic every day to get their medication. But the barriers for a daily clinic visit are often tremendous, from lacking dependable transportation, to having children or work commitments, to not having enough family support.

“The whole purpose of Sonara is to … mitigate the effects of some of these socioeconomic determinants of health. So much of a patient’s recovery success is predicted by things they have no control over,” Giles, whose experience includes stints as a psychiatry resident and researcher at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, said. “Going to the clinic all the time disrupts life. We’re trying to make it so that it’s a level playing field.”

Sonara aims to rapidly build patient-provider trust around medication handling, which will help patients get take-home methadone more quickly, so they stay in treatment and reach their recovery goals.

Rebuilding trust

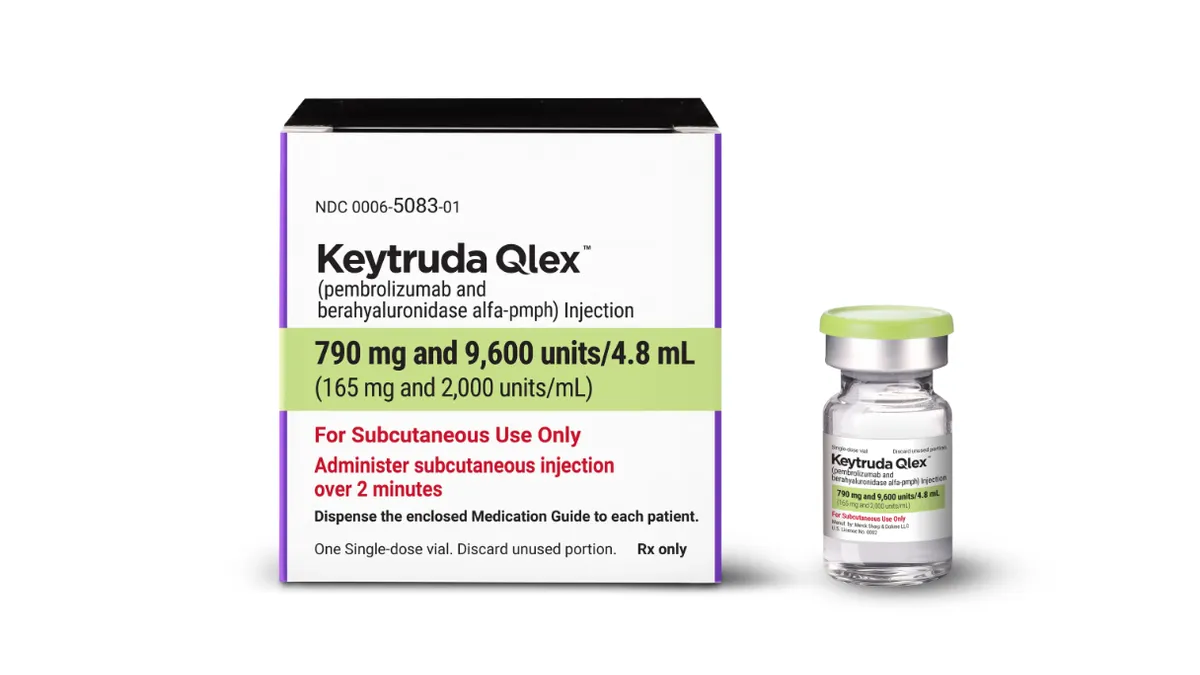

Sonara’s solution uses a two-pronged approach. First, it modifies the standard, take-home methadone bottle by adding a label engineered with a QR code that’s void and then destroyed when the vial is opened.

But what Giles called “the really cool part” is the web browser-based software for patients and clinicians.

“For the patients, it was designed to work on the worst phones available,” Giles said, referring to the low-cost, so-called “Obamaphones” that patients received via Medicaid as part of the Affordable Care Act. Surveys found that even in clinics that weren’t tech-forward, “90% of patients had a suitable data plan or Wi-Fi or a smart device that would work well with Sonara.”

Patients log in to sonara.app using their phone; do a quick camera and microphone test; press a button to start their recording; and scan the QR code while doing so. The app verifies that the code has never been used before, while the clinician watching the video later can see the vial being opened for the first time. Scanning the code voids it, then opening the bottle physically destroys it. The patient takes the medication on camera and ends the recording. The app allows the patient to leave feedback at the end, and a final screen reminds patients to return to the web app again the next day between the clinic’s preferred dosing hours to record their next dose.

Finally, the data is uploaded to the app’s clinician side where it can be reviewed asynchronously when it’s convenient.

“Giving the patient the opportunity to rebuild trust is really addressing one of the core pathologies of substance use disorder.”

Michael Giles

Founder, Sonara Health

A key element of Sonara’s solution involves building trust between the patient and provider, which is why it’s different from other device-based solutions that might work by restricting access to the drug. Not only are they more expensive, but they assume that the patient cannot be trusted, Giles said.

“Maybe there’s a place for those, but that approach is kind of antithetical to what we’re trying to do with Sonara,” Giles explained. He pointed to the fact that an erosion of interpersonal relationships is one of the diagnostic criteria for substance use disorder, making rebuilding those relationships important for recovery.

“That’s a therapeutic component, actually, to our solution,” he said. “Giving the patient the opportunity to rebuild trust is really addressing one of the core pathologies of substance use disorder.”

A broader application

The company is still in its very early stages. It launched its first clinic in February in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district and has since expanded to a handful of other clinics across the U.S. So far, Giles said there have been no adverse events associated with any of the 15,000 doses that have been administered using the Sonara tools, and the company is in the midst of publishing and conducting studies to further validate its success.

For instance, research with Oregon Health and Science University showed that Sonara helps build patient-provider trust; allows providers to give patients take-home methadone earlier; and makes patients feel like it’s easier to stay in treatment. The company also recently received word that its provisional patent for the solution was approved, Giles said.

Although the solution was developed for methadone, it could have applications for any high-cost or high-risk drug, from expensive breast cancer treatments to tuberculosis medications that have public health consequences if they’re not taken properly, Giles said. He also noted the company is in talks with the South Korean biopharma company CrystalGenomics about using Sonara in an upcoming clinical trial for a non-opioid pain medication.

For now, Giles said he is happy that patients express how the tool is changing their lives.

“As a provider it feels really cool to have done something that’s really helping people,” he said.