The human immune system is a powerful ally, helping to fend off disease. But in those with the autoimmune disease lupus it’s the enemy, attacking the body’s own tissues and causing widespread damage.

The question that has long plagued researchers is: Why?

Now, new clues have emerged in the hunt for what triggers lupus, also called systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which could help drugmakers develop better treatments. According to research published last year, the answer might lie in the remains of viruses that have become part of the human genome, called endogenous retroviruses. Akiko Iwasaki, a professor at Yale School of Medicine and an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute was recently awarded the Lupus Insight Prize for her work on this discovery by The Lupus Research Alliance.

For years, scientists have known that endogenous retroviruses play a role not only in lupus, but in others conditions, from cancer to other autoimmune and neurodegenerative diseases to also, potentially, long COVID.

Endogenous retroviruses are sometimes described as virus footprints or fossils. They’re not skeletal remains, but they are lingering remnants of an infection that once passed through an ancestor and became etched into the human genome. As it turns out, they’re not always silent relics. For her research, Iwasaki mapped these retroviruses to get a better view of how they function and found that more than 100 segments are strongly elevated in specific immune cells of lupus patients, fueling the inflammatory immune response that causes the damage seen in people with the disease.

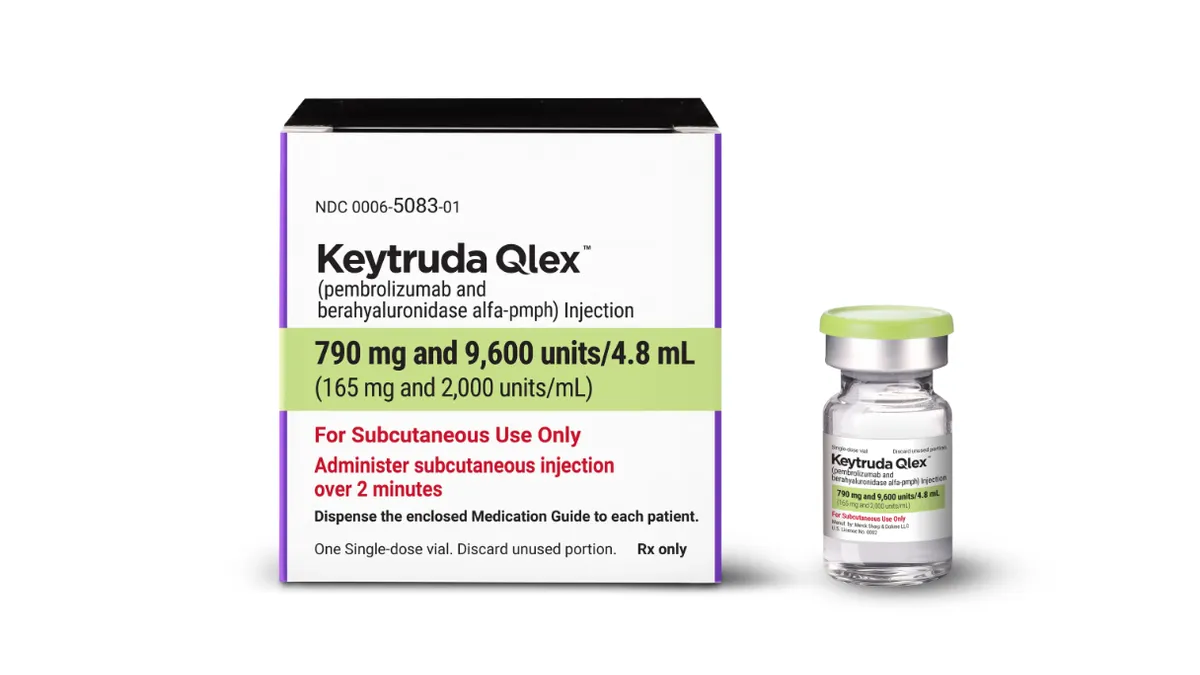

Lupus is a challenging condition because it is often severe and affects multiple parts of the body like the skin, joints and organs. Existing treatments, which merely manage symptoms, are often not enough to provide relief to the 1.5 million Americans and 5 million people around the world with this condition. This is fueling a strong drive for better options, such as biologics and clinical-stage therapies targeting novel therapeutic pathways, and may push the global market for lupus drugs to $3.1 billion by 2027.

As Iwasaki notes, a better understanding of the disease driver could aid these efforts, not only for people with lupus, but for those with other diseases, including long COVID, which may share some features of lupus.

So far, the drug industry has focused its COVID-19 related R&D on vaccines and acute care therapeutics. But given the constellation of symptoms that can plague sufferers of long COVID, the R&D potential in the space remains huge. And more companies — mostly smaller biotechs — are beginning to evaluate a path forward for testing their drugs on long COVID patients.

Here, Iwasaki discusses her work and what it might mean for people with lupus and other diseases driven by a similar mechanism.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

PharmaVoice: Can you tell me a little more about your findings related to endogenous retroviruses and their role in lupus?

Akiko Iwasaki: We've been studying these endogenous retroviruses, which are remnants of retroviruses that have integrated into our genome over millions of years. They occupy a very large percentage of our genome, about 8%, compared to the protein coding sequences that are about 1.8%. The vast majority of biologists focus on this 1.8% of coding genes, but the majority of the genome is not the coding gene, 8% of the genome is occupied by these retro elements, endogenous retroviruses. We wanted to know what they might do to the host physiology.

Many of these genes have been mutated and truncated to the point where they're not coding for proteins anymore. They're just sort of remnants, like fossil records. But there are some, newer integrants that still have the coding capacity. So, we focused on a dozen or so gene locus that still had the capacity to code a protein for the envelope gene of the retrovirus. And these retrovirus envelope genes are expressed in various cell types in the body. So, we wanted to know whether we make antibodies to them, because they looked just like a viral envelope. For the [immune system’s] B-cells, it's very difficult to know whether they came from inside of us or outside. So, what we found was that indeed, many of us make antibodies to these endogenous retroviral envelope proteins. But what's different about the lupus patients is that these antibodies are quite toxic, meaning that when they bind to these envelopes, they are able to engage other white blood cells to become quite activated and stimulated and induce inflammatory responses.

How does this process begin? Is that something that starts, say at birth, or is it triggered by something external?

We are studying the antibody production process itself. We haven't looked at children to see if they develop it early in life, but we believe that [antibodies] accumulate as we age. But in healthy people, they don't appear to be doing anything harmful. Only in the lupus patients these antibodies are modified in such a way that they stimulate the inflammatory responses.

So, there's something unique about people that develop lupus even though other people might have the same type of processes going on in their bodies?

Exactly.

What pieces of the puzzle are still missing to fully understand this process?

We really need to understand better how these antibodies are different in the lupus patients compared to the healthy people, because they're certainly able to engage these white blood cells, known as neutrophils, to become quite stimulated. Neutrophils have been shown in previous studies to be quite active in lupus. What molecular changes are occurring on the antibodies? That's No. 1. And then once we find out those changes, can we then target antibodies that are modified in such a way to prevent this kind of neutrophil engagement? So that could take the form of potential inhibitors or antibodies that target such antibodies, or even targeting neutrophils. So, there are a few different things we can do to intervene with this process once we know what the changes are.

Your research also focuses on long COVID. Can you tell me a little bit about your work in that area?

Since 2020, my lab has really shifted to try to understand both acute and long-term disease from COVID. The recent work is demonstrating something very interesting, which is that when a person has lupus-related antibodies at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis, they're more likely to develop long COVID-19. We've always suspected involvement of autoimmunity in long COVID-19 and pathogenesis and that that may be an interesting link that lupus-like conditions may predispose someone to develop long COVID-19. And if so, is there an involvement of these anti-retroviral antibodies in that pathway. So that's what we're currently working on with the support of the Insight Prize.

So these are not people that already have lupus — these are people that have some of the characteristics that you've found in the people that may go on to develop lupus?

Correct. They don't have full blown lupus. They’ve never been identified as having lupus. They just have low-levels of these lupus-associated autoantibodies. The clinician wouldn't call them lupus because it's below the threshold of what a disease is usually defined with. They have these lupus tendencies, autoantibodies to begin with, and then when they got COVID-19 that predisposed them to develop full-blown like autoimmunity or maybe autoantibodies that can cause these long-term symptoms that long haulers are now suffering from. We don't know exactly what pathways are triggered in these people, but the fact that there is this link between the lupus-related autoantibodies and the development of long COVID-19 and the fact that [like lupus] long COVID-19 also occurs more in women than in men. We're just trying to make any possible links between these observations.

What motivates you to continue this research? Is there something that drives you to understand it better?

It's the suffering, and what patients are dealing with on a daily basis. The long COVID-19 as well as lupus symptoms are so taxing to the health and emotional, and financial status of these people that some people have taken their own lives. They just can't tolerate the symptoms and debilitating conditions that they're dealing with. So that's really what drives me is to alleviate any part of this suffering if I can.