A disease-modifying treatment for Huntington’s disease (HD) has at times seemed within reach — but frustratingly keeps falling out of grasp.

“The last two years have been really challenging for the Huntington's disease community,” Louise Vetter, president, and CEO of Huntington’s Disease Society of America, said.

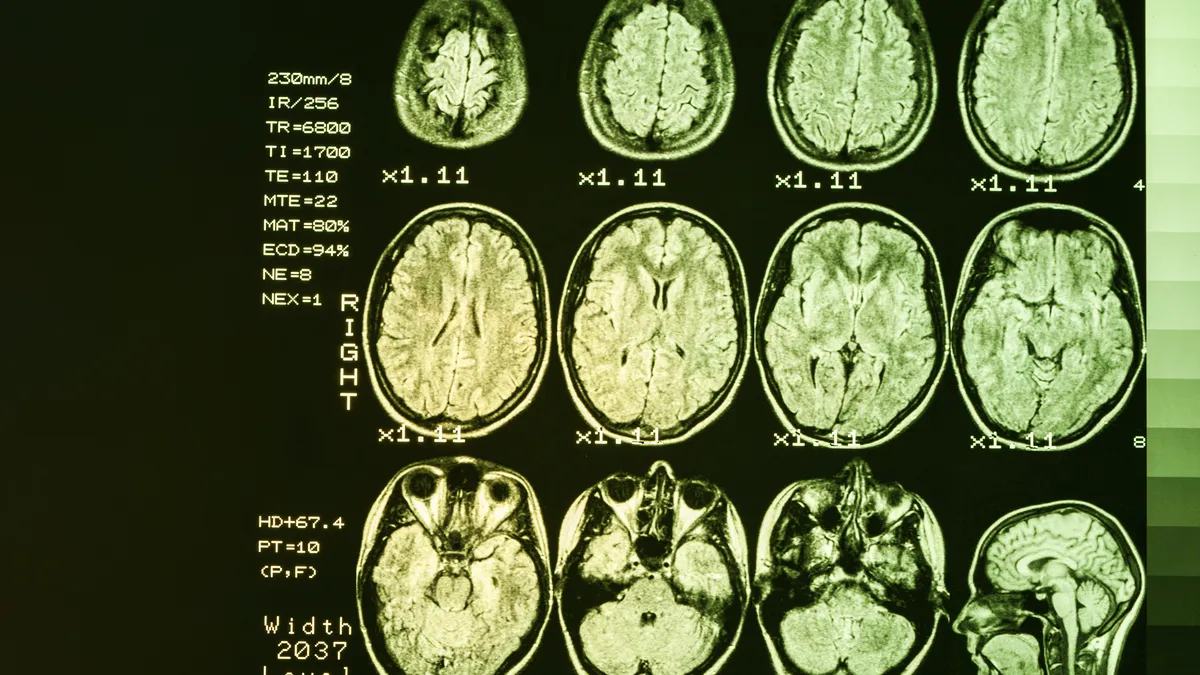

Recent scientific advances seemed poised to deliver a drug that can finally slow or halt the march of this rare and devastating inherited brain disorder, which destroys nerve cells in the brain, causing cognitive, motor and psychiatric changes. But the hopes of many were dashed in 2021 with the back-to-back failures of two companies’ high-profile drug trials.

The first was GENERATION-HD1, a phase 3 trial for the antisense drug tominersen, from Roche and Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Vetter said. The trial ground to a halt last year when the drug not only didn’t improve brain and motor symptoms in patients compared with the placebo but also seemed to lead to worsening symptoms in some patients who took more frequent doses of the drug.

“There was so much enthusiasm. The data looked so good. And then we were reminded that mice aren’t people,” Vetter said.

Within weeks of that failure, Wave Life Sciences announced it was shuttering trials for its drugs, WVE-120101 and WVE-120102, which targeted the mutated form of huntingtin protein after they failed to produce clinical results.

The string of bad HD news continued in 2022.

“This year, we've seen Novartis’s compound Branaplam run into challenges,” Vetter said.

Dosing in a trial for the drug, which could potentially lower levels of the toxic protein that drives the condition, was temporarily suspended in August when researchers noticed some patients had developed early symptoms of peripheral neuropathy, a condition linked to nerve damage.

And a few weeks ago, Triplet Therapeutics, a Huntington’s focused biotech that was also developing antisense drugs, closed its doors after investors in the space pulled funding.

“Even UniQure whose therapy would be revolutionary, and has a lot of hope behind it, got some (negative) feedback related to dosing,” Vetter said.

“There are a lot of shots on goal. We need some of these shots to start slipping through.”

Louise Vetter

President, CEO, Huntington's Disease Society of America

In August, UniQure halted high-dose treatment of its investigational gene therapy treatment, AMT-130, which aims to stop the body’s production of the mutant huntingtin protein, after three of the 14 patients in its phase 1/2 trial experienced adverse effects. Last week, however, the company got the green light to resume enrollment for trials in Europe for patients in a higher-dose group.

Despite the bumpy road for these potential treatments, the HD community, no stranger to adversity, has continued to push forward.

“Everywhere we look, it feels like things are complicated, maybe taking longer than anyone would like. But I think the community is incredibly resilient and recognizes that science is a long, hard road,” Vetter said.

In drug R&D, much is often learned from the bad outcomes as the good. And with a string of HD hopefuls in the pipes, Vetter said there is still room for optimism.

“There are a lot of shots on goal. We need some of these shots to start slipping through,” she said.

Pushing forward

A number of other promising HD treatments are still working their way through development.

“Prilenia Therapeutics has a potentially disease-modifying therapy, pridopidine, that has lots of data over the years and they're hoping to read out in 2023,” Vetter said.

Prilenia’s candidate is currently in a global phase 3 trial for HD, and some patients in earlier trials showed mild improvements in function. The drug helps to clear toxic proteins, and reduces inflammation, protecting brain neurons from damage. The journal, Nature Medicine, named it to a list of 11 clinical trials that will shape medicine in 2022.

And although some of the high-profile antisense therapeutics have taken some hits, they’re still not totally out of the running. Roche and Ionis recently announced that enrollment will begin for a new study of tominersen in 2023. The trial will enroll 360 younger patients with earlier-stage disease in 15 countries. This group was chosen based on a signal seen in the earlier failed trial, which showed this group may have benefited from the treatment.

In addition, Wave has begun testing a third Antisense oligonucleotide (ASOs) therapy, WVE-003. The drug also aims to lower the mutant form of huntingtin protein to slow or halt disease progression. Its 1b/2a trial has seen some early positive signals. The drug appears to be safe and also showed efficacy in lowering these toxic protein levels in patients.

Tackling HD symptoms

However, while a disease-modifying treatment is a holy grail in HD, the importance of finding drugs that can help to manage symptoms should not be discounted, Vetter said.

“The complexity of Huntington's disease requires that we have a really well-stocked toolbox. We have to be able to have different therapies to approach the (various) symptoms of the disease, be it movement, cognition or behavioral. And right now, we're seeing those, in addition to disease-modifying therapies, being developed,” she said.

One anticipated option in this category is a drug from Sage Therapeutics, Sage-718, which is aimed at addressing cognitive symptoms. The FDA has already granted the drug fast track status.

“Sage Therapeutics approach to managing and potentially supporting cognitive health would be a huge breakthrough for HD families because there's currently nothing like that, which focuses on executive functioning and those really insidious symptoms that affect how you think,” Vetter said. “That’s an area of particularly acute need.”

Potential for change

Vetter said she hopes 2023 will bring better news than the last two years to the HD community. More work remains to be done not only in drug development but identifying biomarkers, which will allow researchers to clearly assess treatment outcomes. New biomarkers may also help to identify HD earlier when it is more treatable.

“It is my hope that over the next five to 10 years that we do see drugs being developed not just for those who are mid-to-late stage, but those who are truly in the earlier, even the pre-symptomatic phase,” Vetter said. “That would be huge and I do believe that the field of science is moving that way.”

Overall, while HD progress has been beset by setbacks, Vetter is also hopeful that a turning point is just down the road.

“We're definitely picking up speed,” she said. “It's not a matter of if, it's just a matter of when, and that is my fervent hope that when is very soon.”