Horseshoe crabs have survived over 300 million years, outliving disease outbreaks, mass extinction events and the dinosaurs. But beginning in the 1960s, the crabs faced a daunting new threat.

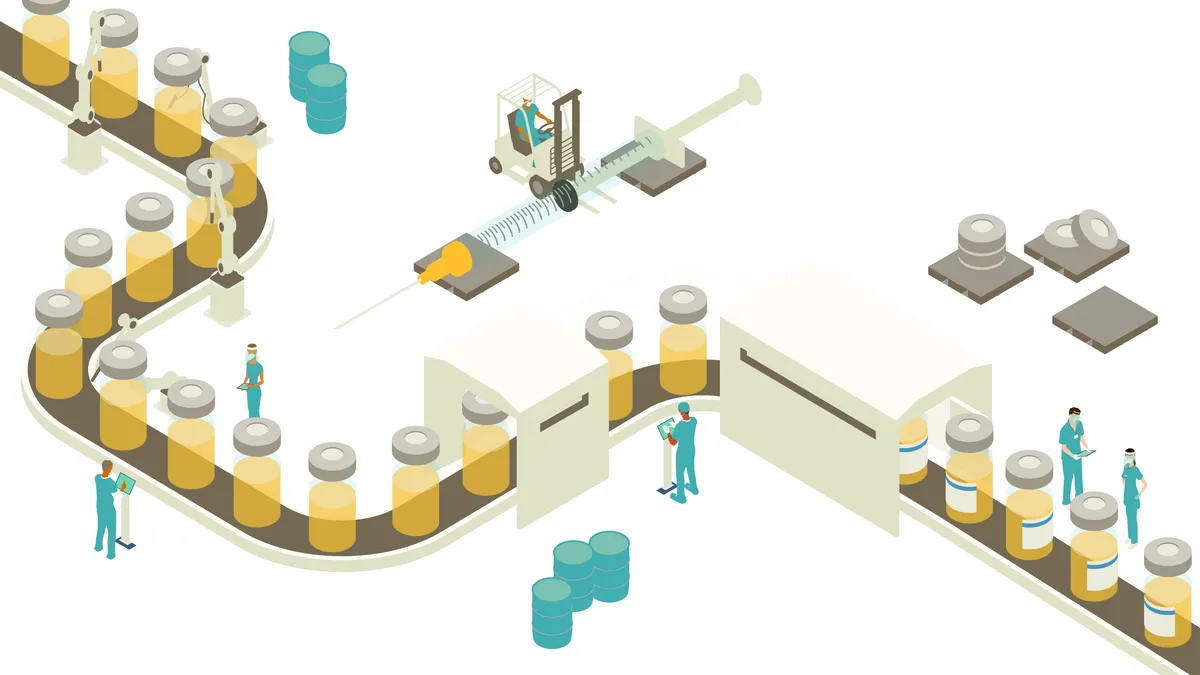

With the discovery that their sky-blue blood forms clots when exposed to toxic bacteria, a primitive immune reaction designed to trap bacterial invaders, the crabs became an integral part of the biopharmaceutical apparatus. Now, the industry uses the blood to make limulus amebocyte lysate tests that screen drugs for dangerous endotoxins, which are impervious to standard heat sterilization methods.

Fishermen capture upwards of 700,000 horseshoe crabs annually to fuel the biopharma machine. Biomedical collectors rig them up, drain 30% of their blood through a hole near their heart and toss them, depleted but alive, back into the waters of the Atlantic, where some 15% of them die from blood loss or stress. It’s big business — their blood is rumored to sell for as much as $15,000 a liter.

But horseshoe crabs, ever the survivors, may soon overcome this threat and become the first creatures spared in a growing push to move away from the use of animals in medical research.

In August, the U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) signaled that it might endorse a synthetic alternative to the horseshoe blood endotoxin test, called recombinant factor C (rFC), which has been around for decades. The organization, which works closely with federal agencies and regulators to set drug standards, issued draft guidelines revised to include rFC in its endotoxin chapter.

The European Pharmacopeia endorsed the synthetic test in 2019, but many companies have hesitated to make the switch until USP signs off, which could happen as early as January 2024.

Moves to reduce animal testing

USP’s draft guidelines are not the only recent step toward reducing industrywide animal testing. Late last year, President Joe Biden signed the FDA Modernization Act 2.0, which no longer requires companies to test drugs on animals before approval. The government mandated animal-based drug safety tests in the 1930s after a batch of contaminated cough syrup killed more than 100 people. But today, several alternatives are poised to replace animal testing.

These tests are slowly gaining credibility and market share and include computer modeling, advanced cell culture assays, organ-on-a-chip technology and AI-driven tests, such as patient-on-a-chip technologies that predict how systems, not just organs, might respond to drugs. The global market for non-animal alternative tests may reach $1.8 billion by 2025, up from $1.11 billion in 2020.

But animal testing will likely continue until industry players and regulators are convinced these tests are equal to or better than animal models, said Jim Corbett, CEO of Emulate, a Boston-based biotech that sells organ-on-a-chip technology. Emulate’s thumb-sized, animal-free testing devices act as mini-models that simulate body functions like breathing or circulation, or disease states, mimicking how a tumor cell might behave in the body.

“We were one of the early innovators in the space,” Corbett said. Today, they market three organ models of a liver, a kidney, and lower intestines, and are investigating a brain chip and a lung chip, each device modified for its intended function to help predict drug toxicity or efficacy.

The company saw an uptick in business when the FDA Modernization Act passed, with interest coming not just from the usual early adopter types, but also increasingly from more mainstream labs.

“The FDA Modernization Act, passed at the end of last year, has galvanized a lot more interest in the area,” Corbett said. “We now see customers that might have been standing on the sidelines before starting to take a lot more interest in implementing the technology.”

The company’s total revenue jumped 40% in the first eight months of this year compared to the first eight months of 2022. It also saw a 90% increase in the sale of instruments needed to run experiments and a 30% increase in first-time customers, he said.

A better option?

It might not be too difficult to convince companies that animal-free alternatives have advantages. Animal research has undisputedly produced broad benefits, but many people find it ethically unsettling. It’s also not that accurate — nine out of every 10 drugs tested in animals ultimately fail human trials.

Corbett thinks animal-free testing technologies have the potential to do better, and Emulate already has some evidence. A study in Nature Briefing found that Emulate’s liver chips beat animal testing results when screening 27 known compounds. Twenty-two of the drugs had already been proven toxic to the liver, and all had slipped through animal testing, which deemed them safe. But the chip technology detected 87% of those toxic compounds, without producing false positives.

"There needs to be more government support in the regulatory agencies to understand these models and to see how we can create the framework for transition."

Jim Corbett

CEO, Emulate

“That's the type of further development that has to occur in the industry to get regulators comfortable and get the scientific community more comfortable,” Corbett said.

For now, animal testing is still the gold standard.

“Animal testing followed by human clinical trials currently remains the best way to examine complex physiological, neuroanatomical, reproductive, developmental and cognitive effects of drugs to determine if they are safe and effective for market approval,” reads a statement from the National Association for Biomedical Research in response to the FDA Modernization Act, 2.0.

A period of coexistence

Corbett said animal testing will likely coexist with animal-free models before a full shift occurs. A reduction in animal testing will likely occur before it’s phased out entirely. For example, a research study might opt to use one animal test and one animal-free test per compound, instead of testing a drug in two different types of animals. Or, as one of Emulate’s clients is doing, using the chips to narrow the field of compounds to the safest ones for use in non-human primates, reducing the number of animal tests overall.

But before a meaningful transition can occur, the technology needs to mature and be further validated, Corbett said. It could also use some regulatory help.

“I'm pretty excited [about] what's happened on a macro level, but there needs to be more government support in the regulatory agencies to understand these models and to see how we can create the framework for transition,” Corbett said.

Some states have taken steps to bring about that change. Maryland passed a law in March of this year to start a fund for alternatives, he said. Funding will come from a tax on research institutes that test on animals. A handful of other states are considering similar measures.

“If we get more things like that happening on the federal and state levels, we’ll be able to accelerate this transition, because there’s a real desire,” he said.

Ultimately, researchers want reliable, predictable results. While they rely on animals today, they’ll gladly make a change if non-animal alternatives prove their worth, Corbett said.

“Everyone wants a better model. Everyone wants to make drug development more productive, and if you can do it by reducing animals, I don't think there's going to be a lot of resistance,” Corbett said. “We just have to get enough government funding behind it to make that regulatory transition.”