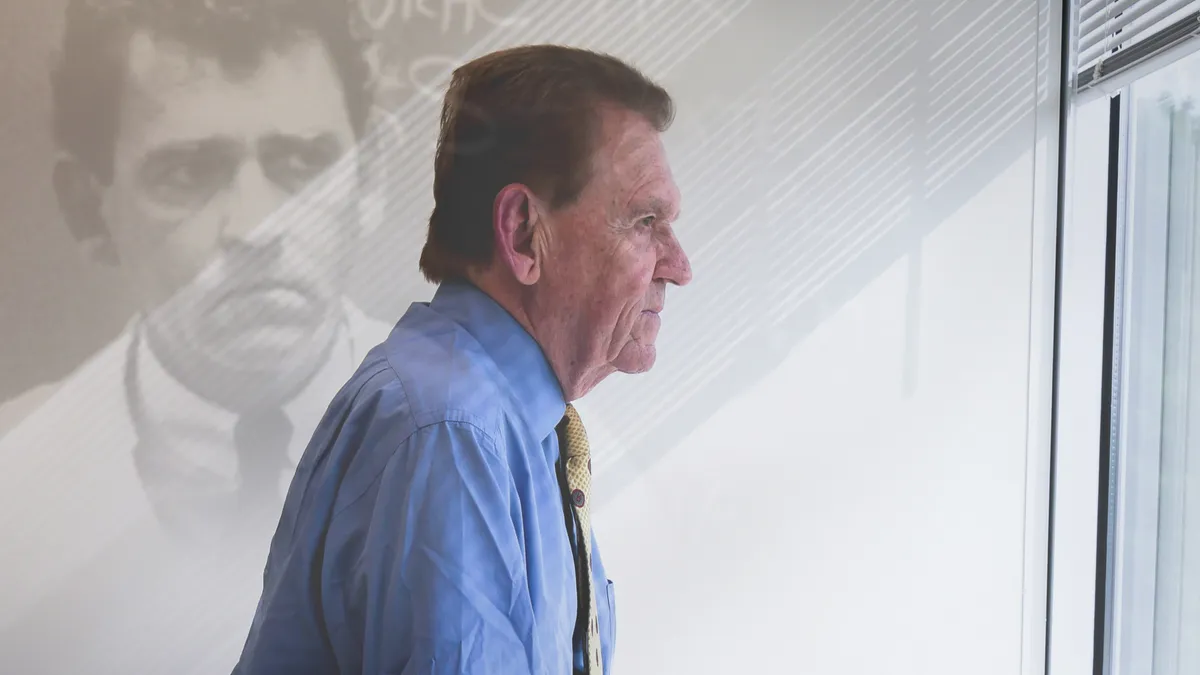

When Dr. Marcus Conant identified the first warning signs of a new disease impacting the gay community in San Francisco in 1981, he was optimistic a solution couldn’t be too far out of reach. More than four decades later, the AIDS epidemic has endured despite a slew of treatment interventions, and Conant’s storied career in medicine still has one major stone left unturned: finding a cure.

Conant, now 87 and serving as chief medical officer at the biotech American Gene Technologies, didn’t enter medicine with an eye toward unraveling one of its greatest infectious disease mysteries. He began as a dermatologist who also dabbled in treating genital herpes — but when he identified Kaposi sarcoma lesions on patients’ skin in the early 80s, he began to see the connection to an emerging health crisis primarily affecting gay men.

“Like many revelations, it didn’t happen suddenly,” Conant said. “It was over time, but then one day, you wake up and realize, wait a minute — this is now my life.”

The road has been challenging scientifically and emotionally for Conant, who’s seen an HIV cure elude developers for almost half a century while many of his patients and friends have succumbed to the disease.

“I have been blessed with good health, both mentally and physically, and I love what I do,” Conant said. “But I had to watch beautiful, brilliant 35-year-old men die, so as long as I'm still healthy and able to do this, that's what I should do, and I'm going to keep doing it.”

Conant’s vision of a world without AIDS is still difficult to fathom considering the many hurdles left, but as the biopharma industry edges closer to long-term solutions for patients with HIV, his longtime work on the front lines has been invaluable to that effort.

“Most people think we've conquered it, that it's not a problem anymore — people can take a pill, but they’ve missed the point that the number of infected people is rising."

Dr. Marcus Conant

Chief medical officer, American Gene Technologies

Now and then

More than 700,000 Americans have died with HIV since 1981, and more than 1.1 million people were recorded as living with HIV in the U.S. last year, according to the HHS. Globally, the numbers are even more staggering — the WHO estimates that more than 600,000 people die each year from the virus and about 1.3 million people were newly infected in 2022.

Despite the loss of life and magnitude of infections, leading drugmakers have developed cocktails that make living with HIV possible. The FDA last week approved a new use of Gilead Sciences’ Biktarvy for patients with treatment resistance. Gilead has a host of other treatments and pre-exposure prophylaxis for patients at risk of infection, a regimen known as PrEP.

Similarly, GSK’s ViiV Healthcare also teamed up with J&J to develop Cabenuva, an injection that keeps patients at undetectable viral levels when taken just once every other month. Long-acting options like these are the closest to a cure that are currently available.

But it hadn’t always been this way, and Conant was there to witness every new treatment that came to market. Journalist Randy Shilts chronicled Conant’s role, along with that of many others, in the critically lauded 1987 book “And The Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic.” From identifying the disease in San Francisco to his fight for recognition by lawmakers and the wider medical community, the early days were fraught and confused, not to mention a dire political minefield.

Conant remembers what Shilts told him when the writer tested positive for HIV in the mid-80s.

“I can remember him saying, ‘If you guys don’t hurry up, I’m not going to make it,’” Conant recounted. “And what we didn’t realize was that what he was saying was really prophetic — when we finally did get highly active antiretroviral therapy, it changed everything.”

Shilts died from complications of HIV in 1994.

The turn of the tide began when the antiretroviral drug AZT — developed by GSK before the company was called that — received FDA approval in 1987 as the first to treat HIV. But it wasn’t until 1995 that protease inhibitors came to the market, and the result was “so overwhelming, we talked about it as the Lazarus syndrome because people were rising from the dead.”

These treatments were too late for Shilts and so many others, but have since established that an HIV diagnosis is no longer a death sentence.

Where is the cure?

By 1987, there had already been attempts at an HIV vaccine, Conant said. But instead of giving researchers hope, these efforts only confirmed this was a more complicated virus than previously thought.

“At first, we thought this was an infectious disease like all of the others and that we were going to have an answer soon,” Conant said. “But those early attempts at a vaccine reinforced the idea that we’re not going to conquer this thing easily — 42 years later, we still haven’t conquered it.”

Public awareness of HIV and AIDS waxes and wanes, and the advent of treatment regimens, while overwhelmingly positive for patients, also contributes to a mindset that holds research back from a more effective solution, Conant said.

“Most people think we've conquered it, that it's not a problem anymore — people can take a pill, but they’ve missed the point that the number of infected people is rising,” Conant said, pointing out that many treatments only work for a part of the population and that the virus tends to gain resistance over time, causing people to unknowingly infect others.

“One of the problems is there are about 40,000 people in the U.S. who have burned through all of the available drugs. And so what's the next step? What's the next drug? What's the next thing we're going to do?” he said.

American Gene Technologies, where Conant is chief medical officer, is among the companies seeking what could become a cure for HIV and AIDS, focusing on the gene therapy AGT103-T. The treatment has passed an early-stage clinical trial with successful safety and tolerability and is entering the second part of the study with a sneak peek at efficacy showing blood markers in the five enrolled patients.

Gene therapies come at a high price, however. Approved treatments in other areas often cost north of $1 million, and because of the nature of HIV, a price like that would prohibit reaching patients in any substantial way — at least at first, Conant said.

“With gene therapy, in my view, cost is one of the major things we face, because it is so blindingly expensive at this stage in development. We know the cost will come down, but on the cutting edge of this technology early on, the costs are just prohibitive, and you've got to find people who are willing to take a risk and invest,” Conant said.

Beyond AGT, academic and industry pipelines contain several more options for a potential cure. Companies like ViiV have programs in place to use antibodies and genetic induction for complete viral suppression. And last year, Gilead’s chief commercial officer told PharmaVoice the company is studying the HIV treatment Sunlenca as a prophylaxis taken every six months and that if successful, the drug could “end HIV.”

“I have been blessed with good health ... and I love what I do. But I had to watch beautiful, brilliant 35-year-old men die, so as long as I'm still healthy and able to do this ... I'm going to keep doing it."

Dr. Marcus Conant

Chief medical officer, American Gene Technologies

But some hopes have also been dashed. One promising HIV vaccine effort from J&J came up short despite reaching a late-stage trial. Last year, the pharma giant shuttered the phase 3 study due to a lack of efficacy, showing that even some of the most well-funded programs are susceptible to failure.

Still, in 2024, Conant isn’t so sure a cure will be available by 2030, a goal set out by many organizations including the WHO and the HHS. During his decades in the space, Conant has seen many deadlines come and go.

“In 1985, no less than the head researcher at the NIH got up on stage and said we will have a cure for this disease in two years,” Conant said. “They always give an aspirational date, usually about 10 years ahead of the point, and unfortunately, I don't see any data that says we'll have it by [2030] even though a lot of other very dedicated people are working on it.”

A substantial part of the problem is that the challenges aren’t just medical, Conant said. Social and political factors weigh heavily on reaching patients to educate, test and treat.

“We have never treated our way out of an epidemic — to stop an epidemic, not only do you have to treat the people who have it, but you've got to protect the people who don't have it,” Conant said. “For example, with an epidemic of measles, you can treat everybody who has measles, but you don't stop the measles epidemic unless you vaccinate people and protect them against that virus.”

Despite a smorgasbord of treatments from top drugmakers and more widespread education, HIV remains an epidemic after more than four decades.

“Yes, we've educated people to go out, get tested, get treated, and the public now thinks that the problem is solved, and we don't have to worry about it anymore,” he said.

‘Disease of perverts’

Conant knew early on that the road to ending AIDS wouldn’t be as simple as only finding a medical solution. As a gay man who moved to San Francisco in the 1960s to pursue a professional career without recrimination, he saw two Americas, and the new virus in the 1980s made that even more clear.

“Sexually transmitted diseases in The Haight [neighborhood] following the ‘Summer of Love’ were a normal progression for a physician working in that area and in that community,” Conant said. “But when you looked at the rest of the country, this wasn’t a disease of young people — this was a disease of ‘perverts,’ and we had to treat them as such.”

At that time, anger drove Conant to doggedly pursue an understanding of the virus.

“What kept me going? The anger that the rest of my country couldn't understand that these were their sons who were dying,” Conant said. “And they were treating them as if they were criminals.”

The U.S. wasn’t the only country where homophobia influenced decision-making in the HIV space. Shilts’ book recounts a time when Conant and other researchers traveled to discuss the problem in Japan, where officials were under the impression that AIDS would never be a problem because there were no gay people in their country. Similarly, when Conant testified to Congress in the mid-80s, he remembers then-U.S. Assistant Secretary of Health Dr. Edward Brandt saying to him: “I’ve never met a homosexual before.”

As politics around LGBTQ issues have evolved, Conant said the prejudices still exist, even if officials are more circumspect about them.

“Those prejudices … don’t go away,” Conant said. “We would not have an epidemic that has killed 40 million people and has another 40 million people infected, because the approach would have been different not only in this country but worldwide.”

From here to there

Biopharma companies have learned over time that individual drugs are less effective against HIV than combinations of therapies. And developing these cocktails required collaboration among companies with their own intellectual property to have a lasting effect for patients.

“One drug company would have a drug that worked, and they realized that unless we work with this other drug company that has proprietary interest for another drug, we don't have a sellable product,” Conant said. “So the thing that drove cooperation was, unfortunately, an economic interest — they had to collaborate, or they would not be able to sell what they did.”

Essentially, the nature of HIV has forced companies with competing interests to work together for a solution and even a cure down the road, Conant said.

Government intervention is also important to promote interaction and cooperation among drug developers, he said.

“There are times when we need to work together, where capitalism perhaps is not going to give us the answer, and that's a situation where government should step in and say, ‘We will reimburse you so you're not going to lose money for developing these drugs,’” Conant said. “Collaboration could have happened much faster if … the government said this is such a threat to a segment of the population that we're going to …reward [companies] for working together.”

Although Conant suspects a true cure — and access to that cure — will take longer than a few more years, he also sees hope on the horizon after so many years of ups and downs.

“How do we stop the AIDS epidemic? Well, we’ve got all the tools right now, but to really stop it, we have to find and treat everyone who’s positive and protect everyone who’s negative,” Conant said. “That’s very complex to do, and unless you do all three, you’re going to fail — but I intend to keep going.”