Ally Schott felt lonely when she was diagnosed with endometriosis at the age of 12. With few treatment options and limited information to go on, she and her family had to become self-taught medical researchers.

Even the diagnosis was the result of Schott’s mother connecting the dots between the pain her daughter was experiencing and the symptoms described by women in a patient organization she had found.

“That's ultimately what convinced my parents that this is what I was dealing with — seeing and reading about the experience of others, and recognizing that I was going through something similar,” Schott said.

In some ways, Schott’s case is rare. Her diagnosis came early, unlike some women who don’t learn they have endometriosis for a decade or more due to lack of disease awareness, misdiagnosis or even bias that assumes severe menstrual pain is normal.

“It's very, very easy to dismiss someone's discomfort if you believe something is meant to be uncomfortable,” said Somer Baburek, CEO and co-founder of Hera Biotech, a biotechnology company developing a nonsurgical tool to diagnose endometriosis.

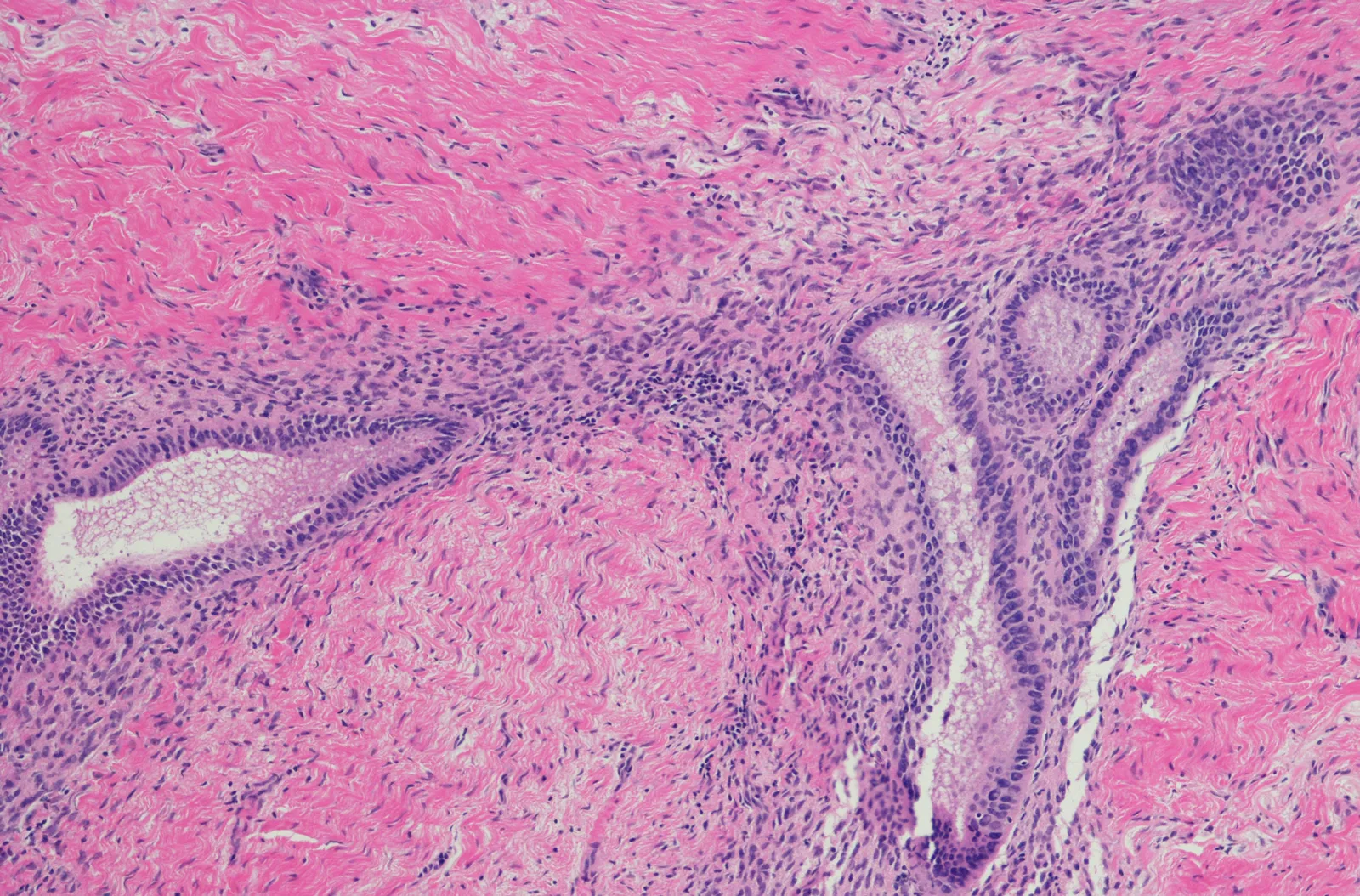

Caused by the growth of uterine tissue outside of the uterus, endometriosis typically affects people who menstruate, but it can occur in post-menopausal women, too. The disease is characterized by chronic pelvic pain, especially during menstruation, but can also cause problems across other parts of the body. It is usually identified through a surgical procedure called a laparoscopy, as ultrasounds can’t always image the abnormal tissue growth.

Although physicians’ understanding of the disease has improved, endometriosis’ root causes remain debated even as it affects some 10% of women and girls globally.

“[Endometriosis research] has been very underfunded and so, despite the prevalence of this disease, it's not very well understood at all,” said Marina R. Walther-Antonio, an assistant professor of surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota and a microbiome researcher.

When Schott received her diagnosis, there was little she could do about it — a reality that frustrated her and her family. “I just felt like I finally had the answer, and that if we had the answer to what was wrong, there would be a solution,” she said. Even since, only two new drugs for endometriosis-related pain have been approved in the U.S.

That pattern is typical of diseases, like endometriosis, that primarily or only affect women. Insufficient funding of women’s health research has stifled development of new products, resulting in prevalent conditions with hardly any available treatments. And while clinical trials are more inclusive than they were in the 1990s and earlier, studies are not always set up to tease out why or how disease symptoms may differ on the basis of biological sex.

Information deficits

Development of a drug is no easy feat for any condition. But the process is more difficult when the disorder isn’t well understood, as with endometriosis.

“We're starting from multiple deficits, and one of them is an information deficit,” said Hera’s Baburek. “And I think that's something that all founders in women's health struggle from.”

For instance, researchers sometimes use biobanks — collections of medical and biological data from tissue, blood and DNA samples — to identify molecular markers of a disease, or develop effective diagnostics. If collected by a government-funded program, the data is often published or made available to scientists, providing a starting point for drug research.

But such resources are more limited in endometriosis, according to Baburek and Joseph Nassif, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine and a clinician. While such work has advanced further in other countries, the U.S. is just getting started.

“So now in the states, we're trying to do a database about all patients who have [endometriosis],” Nassif said. “We have banks for cancer and banks for other diseases. Once you have a lot of patients, we can study it better.”

With less of a foundation, drug developers taking aim at endometriosis, or other women’s health conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome or premenstrual dysphoric disorder, can have a harder time starting out.

“When you're building the ‘data story’ of your company, yours looks weaker than companies who are focused on indications outside of women's health, because they have access to all of those resources,” Baburek said.

Such information deficits have deep roots. Up until 30 years ago, the Food and Drug Administration recommended excluding women of childbearing age from participating in phase 1 and 2 clinical trials, even if they were using contraception. The policies were made in response to birth defects caused by the drug thalidomide, which was prescribed to women to treat nausea in the 1950s and 1960s.

A 1993 law mandated the inclusion of women and minorities in clinical research funded by the National Institutes of Health, but the effects of discouraging women from participating in trials have carried through to today.

For example, a 2022 study found women made up 41% of participants in phase 1 through phase 3 trials for drugs and medical devices run between 2016 and 2019 in the U.S. Women were underrepresented compared to their estimated proportion of the overall patient population for a number of conditions, such as heart disease and psychiatric disorders.

Those research gaps, and the knowledge deficits they can cause, ultimately put the “lives of girls, women and their families” at a “huge disadvantage,” Schott said.

Federal efforts have tried to compensate. Most recently in February, the Biden administration committed to investing $100 million into women’s health research. The FDA also recently updated draft guidance to ensure sponsors run more diverse clinical trials, supporting the Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act of 2022, which requires specific documents and strategic plans.

“It's really important when you're going to try to understand the efficacy, tolerability and safety of a drug that you're testing it in the representative population of people who you anticipate actually using the product,” said Katherine Seay, head of sales and operations at Clinical Trial Media, a patient recruitment and retention company.

Limited options

Compared to other areas of drug R&D, women’s health remains underfunded. An analysis of NIH-backed research found that diseases largely affecting men received more funding. The conditions primarily affecting women that do get investment are typically within oncology, such as breast and ovarian cancer, and reproductive medicine.

Baburek didn’t intend to make reproduction Hera’s focus, for instance. But the company only gained interest from investors when she mentioned the negative impact endometriosis can have on fertility. “While our reproductive organs may be involved in some of these chronic conditions, our ability to reproduce shouldn't be the focus,” Baburek said.

Hera's struggle for attention isn't an anomaly. Despite its prevalence, endometriosis remains low on drugmaker radar screens.

Women with the disease typically take birth control, other hormonal therapies and pain medication to manage symptoms and their menstrual cycles. They may also turn to surgery to either remove the lesions endometriosis causes or, in severe cases, remove their uterus entirely.

When Schott was young, the drug Lupron Depot, a hormonal therapy initially approved for the treatment of prostate cancer, was cleared in the U.S. to manage pain associated with endometriosis. The drug can cause side effects similar to that of menopause and was a “horrific” experience for Schott, who was about 13 years old when it was prescribed to her.

Within the past decade, two other products have been approved by the FDA for pain management with endometriosis: AbbVie’s Orilissa in 2018, and Pfizer and partner Myovant Sciences’ Myfembree in 2022.

The drugs come with hefty price tags: Orilissa and Myfembree each cost over $1,000 per month at their respective list prices. They also don’t address the disease’s roots, and use is limited to a maximum of two years due to their potential to decrease bone density.

“Those options are not widely discussed or celebrated because they're not actually treating the disease,” Baburek said. “[They are] just quieting some of the symptoms that make your life unbearable, but then you get a whole host of other symptoms that also might make your life unbearable.”

Schott was prescribed Myfembree as an adult, but never took it because of its limitations and potential effects on bone density. She says she likely wouldn't take Orilissa for the same reasons.

“For the moment being, we have some ways to manage [endometriosis], whether medical or surgical, definitely with some percentage of success and failure either way,” said Nassif. “But definitely, we need a lot of research for the future.”

A bare pipeline

Neither Orilissa nor Myfembree are big sellers and don’t seem to rate high on their makers’ priority lists.

Three years after Orilissa’s approval, AbbVie tried to sell the women’s health unit the drug was housed in, but the deal never materialized. Sales of the drug are no longer reported individually and are instead lumped in with “other key products” in AbbVie’s earnings report. The last time AbbVie reported Orilissa’s net revenue was for its 2021 fiscal year, when it recorded $139 million in U.S.sales.

AbbVie did not provide additional details about the drug’s development or sales when contacted by BioPharma Dive.

In 2022, Japan-based Sumitomo Pharma agreed to acquire Myfembree developer Myovant Sciences for $2.9 billion. The drug is now sold by Sumitomo in Europe, while Pfizer jointly markets it in the U.S. and Canada.

Pfizer doesn’t report net sales, but lists Myfembree revenue as contributing to “alliance revenue” in financial filings.

The two drugs don’t face much competition. Women’s health company ObsEva had licensed a compound known as linzagolix from the Japan-based biotechnology company Kissei Pharmaceutical. However, the company terminated the deal and withdrew an approval application after the FDA informed it of deficiencies in its submission.

ObsEva shut down operations earlier this year, one of several companies in women’s health that had to refocus its research efforts recently.

Pharma company Bayer has long sold a hormonal drug called Visanne for endometriosis-related pain, but the company has not submitted it for U.S. approval in that indication.

“We focus our research efforts on innovative options in areas of high unmet medical need,” a Bayer spokesperson said in comments to BioPharma Dive. “We regularly review our research and development portfolio to prioritize the advancement of the most promising projects.”

Working with researchers in the U.S. and U.K., Bayer also helped identify an inflammation gene that may be linked to endometriosis. While the discovery seemed to point to a possible non-hormonal drug target, further research “did not end up moving forward into development,” according to a Bayer spokesperson.

Last year, Bayer shifted its focus away from women’s health altogether. While new R&D could still yield women’s health products, a Bayer executive told Reuters that the company’s work in the field overall had “fallen short of expectations.”

Elsewhere, Organon agreed in 2021 to acquire Forendo Pharma in a deal worth $75 million upfront, handing it a drug candidate targeting endometriotic lesions without affecting hormones. Other startups have emerged, including Gynica, FimmCyte and SLBST Pharma.

Looking forward

While endometriosis research continues, Barburek argues that finding a non-hormonal target for treating the condition has to be a priority.

“We've got to mechanistically understand [endometriosis] so we know which levers to pull and which knobs to push,” she said. “So more research needs to go into the mechanistic side of it.”

There is some momentum. Alongside the $100 million the Biden administration pledged to women’s health research, the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, or ARPA-H, also launched a “sprint for women’s health” to fund health solutions for conditions that primarily or disproportionately affect women.

It’s not clear whether such efforts will remain a priority under President-elect Donald Trump’s administration, however. Trump nominated Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to helm the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees health agencies including the FDA. While Kennedy has made clear his views on vaccines and the pharmaceutical industry, his views on women’s health research are less clear and his stance on abortion has been inconsistent.

In a rally prior to the election, Trump said Kennedy is “so into women’s health,” and would let him “go wild” on healthcare.

Some experts worry state abortion bans might hinder recruitment into trials involving in vitro fertilization, or other conditions that might require documenting a woman’s medical history.

“I think, once you take that freedom of choice away from women and leave it in the hands of politicians, state or federal, it's not a great thing,” Schott said. “It's a devastating impact that's going to be further reaching than I think we even have the context to understand right now, and I do think that involves endometriosis.”

Amid such concerns, there is hope of progress in treating endometriosis. Yet, Baburek said, sustained interest and investment will require a “concentrated effort to highlight, educate and draw attention to the issues or consequences of being a woman.”