Welcome to today’s Biotech Spotlight, a series featuring companies that are creating breakthrough technologies and products. Today, we’re looking at Emalex Biosciences, which is developing a novel treatment for Tourette syndrome.

In focus with: Eric Messner, CEO, Emalex Biosciences

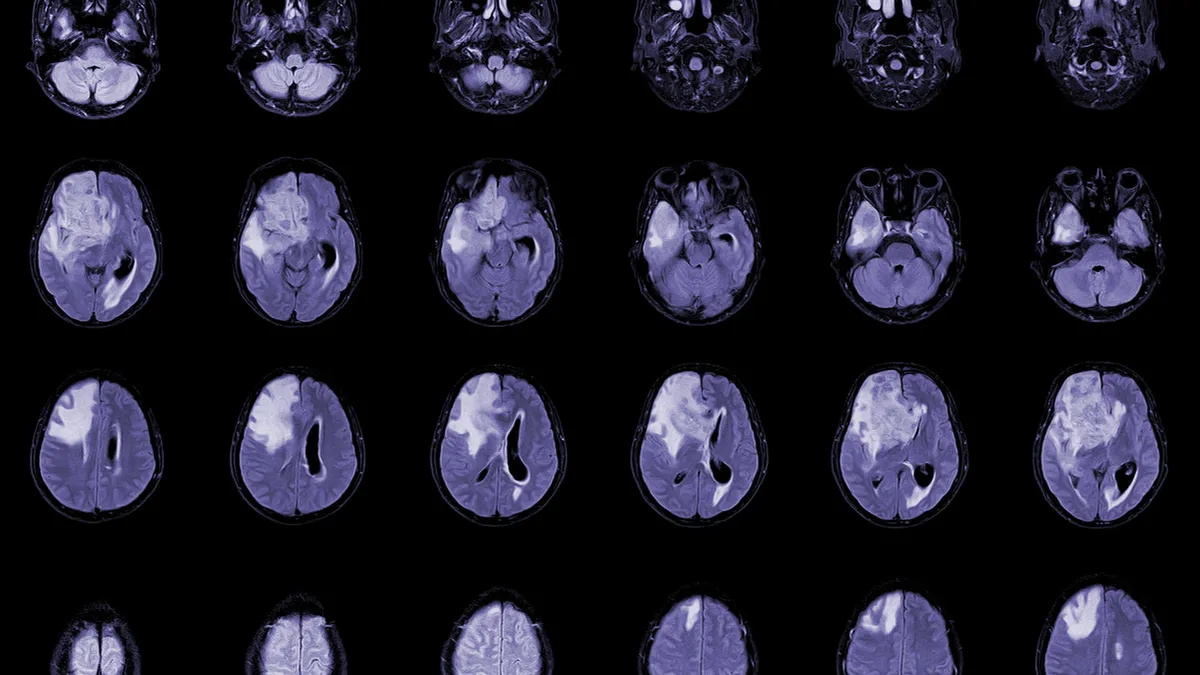

Emalex Biosciences’s vision: To find a better treatment for Tourette syndrome, a neurodevelopmental disorder that most often arises in childhood and causes both motor and vocal tics, sudden involuntary movements or noises.

Why it matters: Tourette syndrome, the most severe type of tic disorder, affects approximately one in 160 children between the ages of five and 17, according to the Tourette Association of America.

“(Tourette syndrome) is a childhood disease primarily, and many children grow out of the disease as they get older. But particularly in moderate to severe patients, which (are) the patients we're targeting, the symptoms typically persist, sometimes even into adulthood,” Messner said.

Today there are only three antipsychotic drugs approved to treat tics, haloperidol (Haldol), pimozide (Orap), and aripiprazole (Abilify), although doctors sometimes prescribe other drugs off-label.

“Unfortunately, there are side effects associated with those (approved) products, in particular, metabolic side effects. They increase blood lipids and blood sugar. There's weight gain with those products. Sometimes they cause unwanted movement disorders,” Messner said.

Even with medication and behavioral treatments, many people don’t find relief.

“So, we know there is a need for new products and new treatments,” Messner said.

A new treatment paradigm: Emalex thinks it’s found a better option — a dopamine antagonist called ecopipam.

The company, one of the first started by the life sciences incubator Paragon Biosciences, gained exclusive rights to the investigational compound after acquiring the neuro-focused Psyadon Pharmaceuticals in 2018. Now, the company is ushering ecopipam, which could become a first-in-class treatment, through a phase 3 trial in hopes it will address the significant unmet need in the Tourette syndrome community, Messner said.

Experts anticipate that the market for Tourette syndrome drugs will grow 10.4% between 2018 and 2028, with demand rising around the world.

“Our intention is to develop this product in the United States and Canada, in Europe, and potentially in Japan,” Messner said.

Investors have been receptive to the idea. In November, the company pulled in $250 million in a series D round of financing. The company is using the funds for what could be a pivotal phase 3 trial.

A crowded field: Emalex is not the only company on the hunt for a treatment. SciSparc, for instance, is currently testing its drug SCI-110, with the synthetic form of THC, dronabinol, in combination with palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), an endocannabinoid. Noema Pharma is also in phase 2a with its candidate gemlapodect (NOE-105), a PDE10A inhibitor and Asarina Pharma, a Swedish biotech, is testing Sepranolone, a drug targeting a neurosteroid in the brain that is thought to fuel tics.

"We know there is a need for new products and new treatments."

Eric Messner

CEO, Emalex Biosciences

What distinguishes ecopipam from existing Tourette treatments is its unique mechanism of action, Messner said. The drug is a dopamine antagonist, but unlike many antipsychotics, which target the D2 receptor, ecopipam aims at the D1 receptor. People who took ecopipam in the phase 2 trial saw their symptoms improve. While it isn’t a cure — the tics don’t go away 100% — “they’re less significant and less severe,” Messner said.

Patients in the trial also didn’t experience the weight gain or metabolic changes other Tourette drugs can bring, Messner said. However, some did report headaches, nausea, insomnia, and less commonly, anxiety. And while a small percentage of patients in the phase 2 trial discontinued the drug due to side effects, more than 90% of eligible patients opted to keep taking it in an open-label extension following the trial.

“We saw that as a very positive sign that patients were pleased with their experience on the product and wanted to continue,” Messner said.

They’re hoping that the phase 3 trial, which is currently enrolling some 200 patients and recently began dosing participants, will produce similar safety and efficacy results.

At the outset of the trial all participants will take ecopipam, but at the 12-week mark half will stay on the drug while the other half will shift to a placebo. Messner said they will then compare the relapse rate for people taking the active drug versus the placebo 12 weeks later.

“It will take approximately two years. We expect the trial to run throughout 2023 and finish at the end of 2024, and we hope to have top line data at the very end of 2024, or sometime in the first half of 2025,” he said.