At the start of 2024, optimism had returned to biotech. Investor cash flowed back toward drug companies and initial public offerings, a useful barometer of the sector’s health, picked up in a sign of the market’s strengthening.

But IPOs have since slowed. At least as of now, they are on track to roughly match the number of offerings priced in each of the last two years — more of a plateau from the downturn of the past two years than a resurgence. Taking their place have been private biotech acquisitions, a phenomenon industry watchers say is driven by the abundance of mature, but not yet public, drug startups.

"Because companies have not gone public, which they might have ordinarily done, there's actually more of a later-stage pipeline that is still private,” said Naveed Siddiqi, a senior partner at Novo Holdings, the parent company of Novo Nordisk that manages a venture investment portfolio.

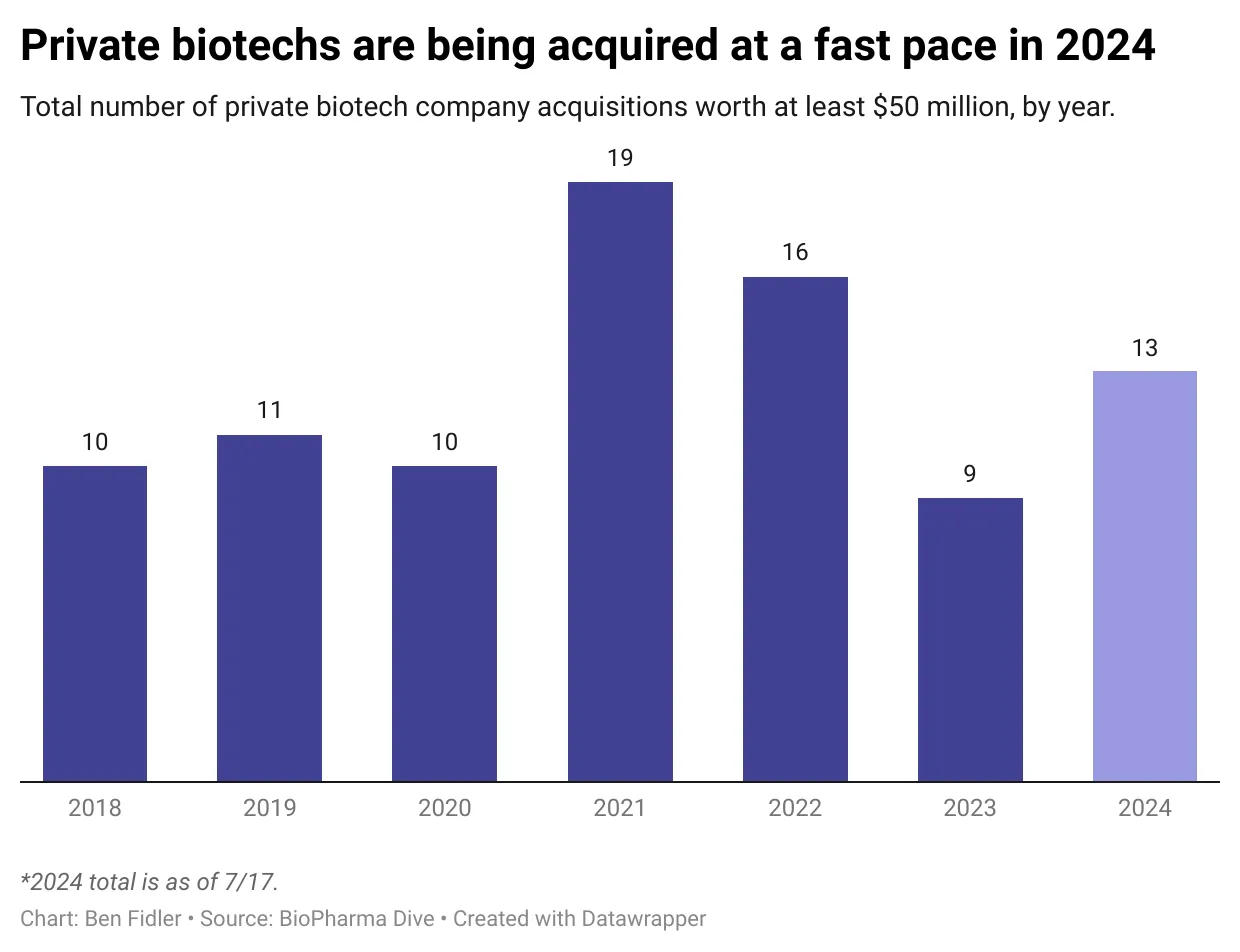

As of mid-July, 13 of the 26 acquisitions worth at least $50 million in upfront value this year were of private biotechs, surpassing the pace set in each of the previous six years, according to BioPharma Dive data. In a research note last month, analysts at the investment bank Jefferies noted how the share of buyouts involving startups is by far the highest of any year since 2015.

M&A is a crucial piece of the biotech ecosystem. Acquisitions help pharmaceutical companies build their pipeline, while giving biotechs and their backers a financial return on their investment. Typically, most deals involve publicly traded companies, which have advanced far enough along to prove their science has real merit. Some of 2023's top deals included Bristol Myers Squibb's buyout of schizophrenia drugmaker Karuna Therapeutics and Merck & Co.’s purchase of immune drug developer Prometheus Biosciences, both of which had traded on the public markets for several years.

Recently though, pharma companies have increasingly turned their attention to private biotechs.

According to a report published last week by HSBC Innovation Banking, the shift began in the second half of last year, when most of 2023's private M&A deals took place. The change in pattern suggested a "valuation capitulation" by private biotech companies and their investors that set the stage for an upswing in startup M&A, the report said.

Not only has the pace of these deals climbed, but their size has as well. Seven deals exceeded $1 billion in total value, and the median size of upfront cash involved was more than three times the average of each of the previous six years, according to the report.

Jon Norris, a managing director with HSBC Innovation Banking, said these premiums leave companies with a "very strong bird in hand" at a time when the IPO market is "iffy." A majority of the 2024 IPO class trades at share prices well below their debut value, and good news often isn't met with a bump in value, he said.

Is it better to "go public, get more clinical data — which could be good or bad — and wait for the value inflection point?" Norris said. "It could be huge, but if you look at it, the median returns for IPOs this year are negative."

Pharma companies have strong incentives to find new drugs this decade, as many of the industry's top-selling medicines are set to lose patent protection. That looming “patent cliff” has led to speculation about a significant increase in dealmaking.

Public companies are usually the first to be scooped up. But the sector's IPO slowdown over the last few years has created a glut of biotechs that haven’t yet made it to Wall Street. Those companies are “still private and awaiting the right window to go public," wrote Jefferies analysts last month, and "explains why many M&A deals have taken place in the private sector."

The type of startup now getting acquired bears that theory out. Most had a drug candidate in human trials when they were bought, and seven were in or nearing phase 2 testing. Eight were involved in immunology, a field of research that’s drawn increased interest from investors of late.

Hi-Bio, which sold to Biogen for $1.15 billion in May, is one example. The company was formed around a pair of immune disease drugs licensed from biotech MorphoSys. It brought both into clinical testing, and earlier this year claimed success in two phase 2 studies, all while remaining privately held.

As those programs advanced, Hi-Bio began evaluating its options, according to CEO Travis Murdoch. But an IPO wasn’t the company’s “primary consideration.” Additionally, bankrolling multiple phase 3 trials, and building commercial infrastructure, would have required a very large capital raise. The company had to balance what was best for its shareholders, employees and the future of its drug research.

“That’s a complex decision,” Murdoch said. But obtaining phase 2 data is “a very natural inflection point,” after which “acquisitions often happen.”

Other biotech companies may be making similar decisions to give their experimental medicines a better chance at being successfully commercialized, he said. Celsius Therapeutics reportedly had first intended to build itself independently. But as it ran into trouble raising funding, the company last year pared back research and cut most of its staff. It sold to AbbVie in June, after completing a phase 1 trial.

Investors backing private biotechs may be more open to deals, too. Limited partners that support venture funds are “looking for liquidity,” said Novo Holdings’ Siddiqi. With IPO prospects uncertain, M&A deals give investment firms another way to generate returns.

Still, he said, “there is a willingness to listen, but not a willingness to transact at any value.”

In parallel, pharma has greater comfort with dipping into the private markets for deals. Michael Cohen, co-leader of law firm Brown Rudnick’s venture capital group, said large drugmakers are getting to know emerging biotechs earlier and earlier now, so they’re “well positioned to engage in M&A activity when the time is right.”

Better bargains may also be had on the private side, where a more advanced drug prospect could be less expensive than if it were owned by a publicly traded company.

“If your asset happens to be sitting in a public company that is worth $10 billion in M&A, then pharma would have to jump through more hoops to justify the acquisition price,” said Carolyn Ng, a partner and managing director at TPG Life Sciences Innovations.

AstraZeneca, for example, acquired privately held Amolyt Pharma in March for $800 million upfront. That price makes Amolyt’s buyout one of the larger startup deals this year. Yet it is far less than recent multibillion-dollar acquisitions of Morphic Holding and Alpine Immune Sciences, despite the fact that, like those companies, Amolyt has a drug in advanced testing.

“In other circumstances, Amolyt would’ve been a public company,” said Siddiqi of Novo Holdings, which invested in the company. "Because markets have been shut, there's more substrate around at later-stage, still private [companies]," he added.

They’re now able to “still have their cake and eat it slightly later."