As quickly as they rose to prominence during the pandemic, many biotechs fell just as rapidly back down to earth.

When pharma’s R&D push peaked, hundreds of vaccines and treatments were in development to combat the novel coronavirus. And while the remobilization turned once-obscure biotechs like Moderna into household names, a host of other companies that had suddenly emerged into the spotlight ultimately faded as their candidates faltered.

In a journey that mirrored that of the wider biotech world, the initial “sugar high” of investment dollars led to a crash for most companies as capital drained from the market. In the wake of that reckoning, many biotechs have had to restructure in a tighter financial market and pivot to alternative areas of potential growth.

Here’s where four biotechs have landed since their initial ascent to COVID fame.

CureVac

The backstory: When the pandemic began, Germany-based CureVac had already been plugging away at mRNA technology. In fact, CureVac, which launched in 2000, claims to be “the world’s first” to “harness mRNA for medical purposes.” As such, the company was poised to become a key player in the COVID vaccine race, and by June 2020, it headed into phase 1 trials with its candidate CVnCoV.

Despite early-stage results that appeared encouraging, CureVac reported efficacy around 47% in a phase 2b/3 trial — far below its mRNA rivals — and development was dropped. Many scientists initially expressed dismay at CureVac’s clinical stumble. But the mismatched results compared to other mRNA shots was ultimately blamed on CureVac’s use of unmodified mRNA (as opposed to the modified mRNA in the shots developed by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna), which CureVac’s CEO Alexander Zehnder said would likely work better in therapeutic areas like cancer.

Where they are now: CureVac was down but not out. After its COVID setback, the company re-evaluated its mRNA technology, established a restructuring plan and looked to build on its pandemic-era lessons.

Earlier this year, CureVac restructured a deal with vaccine heavyweight GSK originally struck in 2020 to bolster development of the pharma giant’s infectious disease-focused pipeline. The partnership gave GSK full development and commercialization rights to CureVac’s COVID and seasonal flu candidates in phase 2 and an avian influenza shot in phase 1 for over $1.5 billion in upfront and potential milestone payments.

In its third-quarter earnings report released this week, the company said its “corporate redesign,” which includes a 30% workforce reduction, is set to deliver “significant annual cost savings” next year. Like Moderna, CureVac is also aiming to leverage mRNA in cancer and is in early-stage development of personalized and off-the-shelf cancer vaccines.

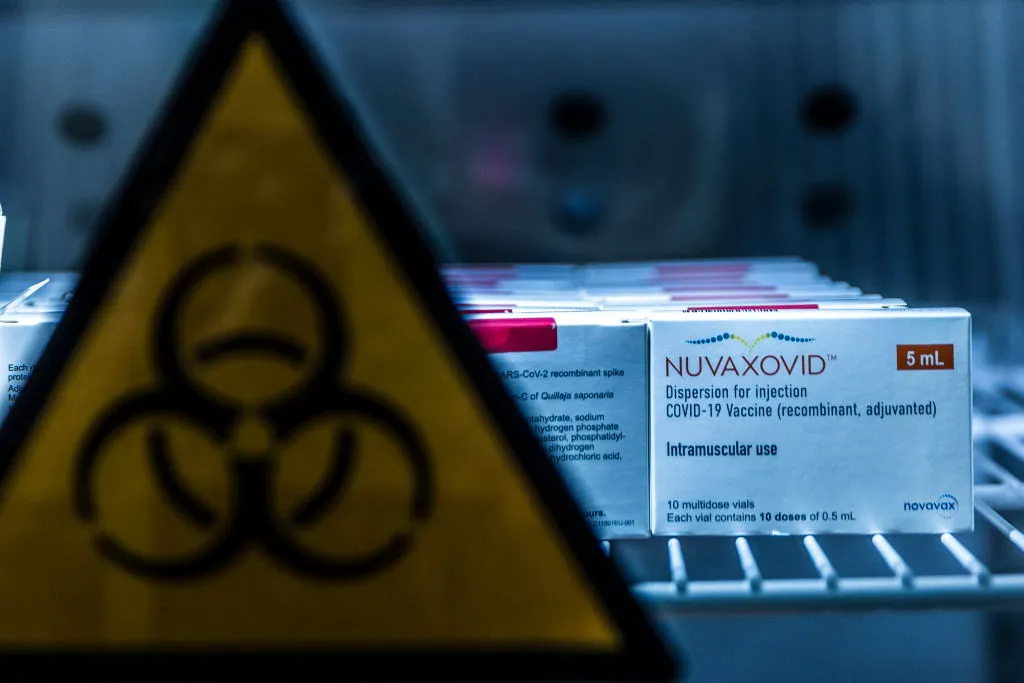

Novavax

The backstory: Like CureVac, Novavax was an early and strong COVID vaccine contender. After a few clinical setbacks, Novavax eventually scored an FDA nod for its shot in 2022. But despite the Novavax jab offering a traditional protein-based option to mRNA-shy patients and studies suggesting it could have fewer side effects and longer durability, the company has struggled with uptake.

Commercialization challenges hit a fever pitch earlier this year when activist investor Shah Capital publicly called out the financially fledgling company for “colossal market failures” and demanded a leadership “shakeup.”

Weeks later, Sanofi extended Novavax a lifeline through a partnership to commercialize its COVID shot and co-develop its combo flu/COVID candidate.

Where they are now: The Sanofi tie-up in May funneled $500 million into Novavax’s R&D coffers and could be worth up to $700 million more if it delivers on development and regulatory milestones. So far, the road to hitting those targets has been rocky.

In October, the FDA slapped a clinical hold on a trial of its flu/COVID shot after a “serious adverse event of motor neuropathy.” The company was OK’d to resume testing earlier this week.

In its latest earnings report, Novavax also lowered its full-year guidance from a high of $800 million in revenue to $700 million at the top of the range. The company, which slashed R&D investments and its staff to cut costs, also said it inked an agreement with a “leading pharmaceutical company” related to its proprietary Matrix-M adjuvant.

Inovio Pharmaceuticals

The backstory: While Inovio Pharmaceuticals was once a promising frontrunner in the COVID vaccine hunt with its DNA-based technology, the company also became quickly mired in controversy.

A decade earlier, Inovio had been developing an H1N1 shot and in later years reported positive clinical results for malaria and Zika vaccines. While this progress maintained financial momentum for its clinical work, Inovio failed to bring a product to market.

By August 2020, the company appeared to be repeating that pattern, and a group of shareholders filed a class action suit against Inovio claiming it released misleading statements about the COVID vaccine to bolster stock prices.

By 2022, the company gave up on its COVID shot, which would have required a specialized device for administration, and pivoted to developing the candidate as a booster instead.

Last year, Inovio settled the class action investor suit for $44 million.

Where they are now: With its COVID booster still in late-stage development and several other DNA-based candidates including HIV and cancer medicines in the clinic, Inovio announced in January that it planned to file an application for its lead candidate, which treats recurrent respiratory papillomatosis, under the FDA’s accelerated approval program. But the company hit a snag when the application was delayed due to manufacturing concerns related to its delivery device.

Inovio is now targeting mid-2025 to submit its application, according to an earnings report released this week. The company also noted that its cash runway currently extends into the third quarter of next year.

Veru

The backstory: Even with several approved vaccines on the market, hospitalization and death rates from COVID remained stubbornly high in 2022 — a challenge Veru looked poised to address with its antiviral and anti-inflammatory treatment sabizabulin. In fact, Veru halted its study of the drug in April 2022 because the results were so positive it was deemed unethical to continue administering a placebo to patients.

With good-looking safety and efficacy data in hand, Veru strode confidently into Emergency Use Authorization talks with the FDA and prepared to commercialize the drug for acute respiratory distress syndrome.

But it wasn’t meant to be. In November 2022, an FDA adcomm voted against approval due to the small sample size of Veru’s sabizabulin trial, and Veru reported in March 2023 that the agency had denied its EUA application.

Where they are now: While the FDA offered Veru guidance on designing a confirmatory phase 3 trial for sabizabulin, it has since stopped development until it receives funding from “government grants, pharmaceutical company partnerships or other similar third-party external sources,” the company said in an email.

Instead, Veru, which has one commercialized product in the sexual health market, has jumped into the red-hot GLP-1 arena. With late-stage development for sabizabulin in breast cancer also paused, Veru is throwing its clinical energy behind a selective androgen receptor modulator called enobosarm.

“Our goal with enobosarm is to preserve muscle mass while patients are on therapy with GLP-1s,” the company said. “We are currently in a phase 2b study with data expected in January 2025.”