When Novo Nordisk’s holding company announced plans to acquire contract manufacturer Catalent for $16.5 billion in February, the deal faced swift public backlash and an inquiry from the Federal Trade Commission. As the year winds down, the deal’s potential impact is still up in the air, and Big Pharma rivals have joined the chorus of opposition.

The deal would help the Danish drugmaker secure manufacturing capabilities for its popular weight loss and diabetes drugs Ozempic and Wegovy. Novo has struggled to keep up with demand for the products, landing Wegovy on the FDA’s shortage list.

The pharma already works with Catalent, and in connection with the acquisition plans to acquire three fill-finish Catalent sites for $11 billion from parent company Novo Holdings to manufacture GLP-1 drugs.

Novo’s plans encountered antitrust concerns from lawmakers, consumer groups and other Big Pharma companies alike as the weight loss drug market grows toward an estimated $100 billion or $200 billion by 2030. As one of the largest contract manufacturing organizations in the industry, Catalent also works with Eli Lilly, the other leading pharma company in the current GLP-1 landscape.

Just this month, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) asked FTC Chair Lina Khan to “closely scrutinize” the proposed deal, noting that Novo has a 55% market share for GLP-1 drugs. A pack of consumer groups and unions also joined together to ask the FTC this month to halt the acquisition on the grounds it would be “harmful” to competition in the weight loss industry and impact gene therapies.

Now, with other drugmakers looking to enter the obesity market, Novo’s acquisition efforts are also coming under fire from a potential competitor.

Roche’s market interest

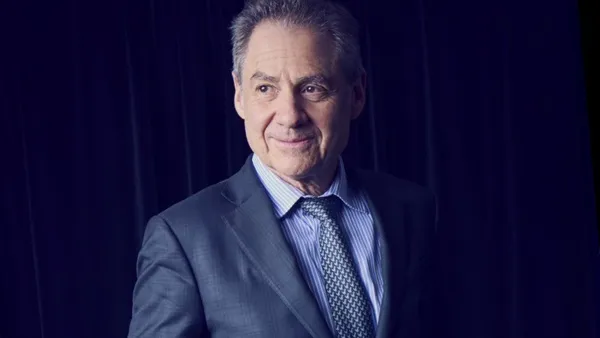

Roche is the latest to pile on to the deal’s opposition, calling on authorities to block the acquisition. The Swiss drugmaker is currently advancing a pipeline of three obesity and diabetes drugs it picked up in a $2.7 billion takeover of Carmot Therapeutics.

"Limiting the competition in this space is not a good idea," Roche's CEO Thomas Schinecker told media outlets last week. "From an industry perspective, it would be a wrong decision by authorities."

According to Schinecker, Roche has the manufacturing capacity it needs for its obesity and type 2 diabetes GLP-1 medications under development. However, he voiced concern for smaller pharmas that may lose access to contract manufacturing organizations through market consolidation.

The insider information Novo would gain with regard to the burgeoning field could cause some conflicts along the way, said Janel Firestein, partner and life sciences industry lead at Clarkston Consulting, in an email.

“Reduced production access aside, there would still be concerns the acquisition would provide Novo Nordisk with substantial insights to production processes, operational strategies and manufacturing bottlenecks, which in turn would give them a considerable competitive advantage,” Firestein said.

Roche’s weight loss and diabetes meds could rival Novo’s down the line, although they are still in early stages of development. The pharma giant expects phase 1 data from one diabetes and obesity treatment, the GLP-1/GIP CT-388, in late 2024 with plans to present the data in 2025.

Roche is also focusing on phase 2 data for another GLP-1/GIP candidate, CT-868, for type 1 diabetes patients, and additional phase 1 data for CT-996, a type 2 diabetes treatment, in 2025, Schinecker said during the earnings call.

Lilly’s part

Eli Lilly, Novo’s current rival in the GLP-1 market, has its own concerns about the merger. Lilly uses Catalent to manufacture GLP-1 drugs, Zepbound and Mounjaro, CEO David Ricks said during the company’s second quarter earnings call in August.

“We do rely on one of the Catalent sites for GLP-1 and other diabetes production,” Ricks said. “It's more the oddity of your main competitor being also your contract manufacturer and how to resolve that situation.”

However, Lilly has been building up its manufacturing capacity, pouring $9 billion into an Indiana facility in May to boost production of the active ingredients in its GLP-1 injections and other medicines. The company has committed $18 billion toward its manufacturing prowess since 2020.

But Novo Holdings maintains Catalent isn’t a major contractor for Lilly.

“Catalent has no role in the commercial manufacturing of Eli Lilly’s Zepbound and Mounjaro products,” the company stated on its website about the deal.

Eli Lilly declined to comment to a request for clarification over Catalent's role in manufacturing its GLP-1 medications.

Where the deal stands

Currently, Novo Holdings’ proposed deal is under review by the FTC, which asked for additional information related to the acquisition in May. The merger was originally expected to close toward the end of 2024, according to Catalent.

The FTC has increased scrutiny of large deals in pharma and other industries as of late, and Novo and Catalent may need to make concessions before carrying through with the merger.

“The highly competitive nature of this industry, the sharp rise in GLP-1 drugs, and competitive dynamics therein and already-constrained supply chains has forced even more pressure on this deal,” Firestein said.

As opposition to the deal has crescendoed, Catalent has attempted to quell market concerns. CEO and president Alessandro Maselli released a statement last week in an attempt to dispel “inaccuracies” surrounding the deal. Namely, Maselli stated the CDMO would continue to partner with pharma companies to bring products through development and clinical trials, as well as continue its fill services. Catalent shareholders have already approved the deal, which would take the company private as proposed.