When an FDA advisory committee voted unanimously to recommend Eli Lilly’s Alzheimer’s drug donanemab for regulatory approval this week, the decision solidified another significant milestone in a field that had been deeply stagnant for years.

From 1998 to 2017, a meager 2.7% success rate fueled widespread disappointment in Alzheimer’s drug development with 146 treatment failures and four new therapies that only treated symptoms of the disease, according to a 2018 report from PhRMA. Since that time, just two drugs have been approved in the U.S. to treat the suspected underlying causes of the disease — Aduhelm and Leqembi, both from partners Biogen and Eisai — and Leqembi is currently alone in the market.

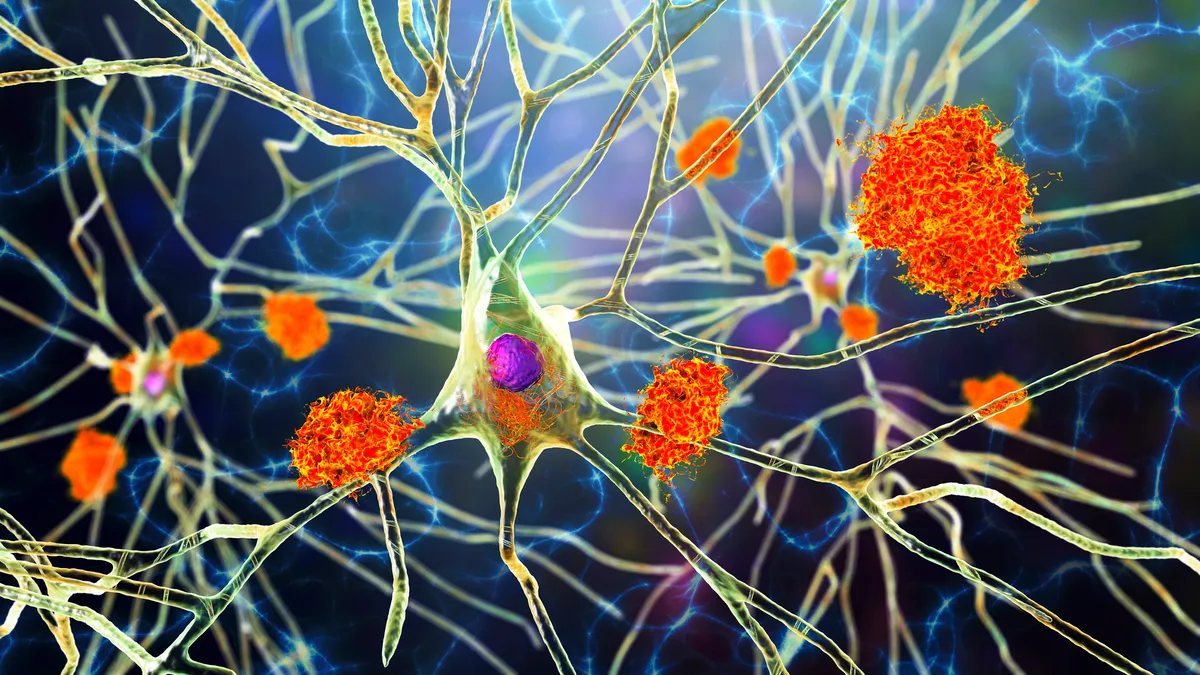

Both anti-amyloid drugs are just the tip of the spear for Alzheimer’s treatments, though, according to Dr. Howard Fillit, co-founder and chief science officer of the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation. Many of the voting members of donanemab’s advisory committee agreed that while donanemab is effective and worth the risk of side effects that include brain swelling called ARIA, more clinical trials will give a clearer picture of the exact outcomes for anti-amyloid drugs.

“If approved, donanemab will expand the first class of disease-modifying drugs, serving as the building blocks for future generations of drugs,” Fillit said “Anti-amyloids are not a silver bullet, but they offer opportunities for patients to modify the course of the disease while the field works towards developing more novel therapies that target the underlying biology.”

Leqembi and donanemab are limited by their applicability in certain patients — both have been aimed at patients in the early stages of Alzheimer’s who have also undergone a PET scan to determine levels of amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the brain.

Furthermore, the amyloid theory itself has come under fire. Although the two drugs have demonstrated an ability to clear plaque, researchers have noted their effect on cognitive function is less apparent. Leqembi and donanemab improved cognitive and clinical progression in trials, but that linear progression has been questioned.

So, as anti-amyloid successes ring out in Alzheimer’s circles, many in the field are also looking to newer options and alternative targets for the next big win. Here are some of the leaders in the clinical anti-amyloid and anti-tau pipeline that could play a role in future treatments.

Anti-amyloid holds the lead

While some researchers believe amyloid may not be the most effective target to treat the underlying cause of Alzheimer’s, many drugmakers are pursuing it because of its long research history and measurable parameters of success in the clinic. With almost three approvals in the bag, the regulatory process has become less of an unknown factor, as well.

Despite a failure in the marketplace, Aduhelm still remains the subject of two late-stage clinical trials from Biogen to further link the clearance of amyloid to reduced cognitive decline. The phase 3 trials are designed around efficacy versus a placebo and long-term effects over the course of a year. Despite these trials, Aduhelm is also facing Lilly’s donanemab in a head-to-head trial to determine which is better at clearing amyloid plaques.

Eisai and Biogen are aiming for further penetration of their drug Leqembi, as well, driving large clinical studies to determine cognition benefit, long-term results and different mutations of the disease.

There are also some newer molecules that haven’t gone through the regulatory process but have made it to phase 3. Lilly has two of them — remternetug and solanezumab — both monoclonal antibodies designed to clear amyloid plaques. For solanezumab in particular, Lilly was testing prevention, but found that the drug did not clear plaques or slow cognitive decline.

Some companies are going the small molecule route for amyloid clearance, such as Alzheon and Cassava Sciences, both of which have a late-stage candidate in the works.

Tau’s rise

Big Pharma is especially interested in advancing therapies that clear tau tangles in the brain, another hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease that is thought to be one of its causes. Roche, Biogen, Eisai, J&J and Eli Lilly are among the pharma giants with anti-tau candidates in clinical trials.

Tau, which normally stabilizes brain cell structures, has been found to grow out of control in Alzheimer’s patients, and the ensuing tangles can become toxic to brain cells. Similar to amyloid clearance, these drug candidates aim to break down tau proteins.

Roche, which has been beset by several late-stage disappointments in Alzheimer’s, is carrying its anti-tau candidate through phase 2 in collaboration with UCB. Biogen, Eisai, J&J and Lilly have also made it to mid-stage trials that are ongoing.

But the anti-tau theory is facing similar challenges as the anti-amyloid camp. While some big drugmakers are still attempting to make anti-tau work, a series of failures has given researchers pause: “It is time to reconsider subjecting patients to the removal of physiological levels of soluble [amyloid beta] and tau and to concentrate our efforts on understanding why, in AD and tauopathies, [amyloid beta] and tau begin to aggregate in the brain to form deposits,” according to a 2023 paper.