Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) are an increasingly powerful tool against cancer. And now, with Pfizer's recent acquisition of ADC maker Seagen, the space is attracting even more attention as the next big niche in the industry.

More than 20 years ago, Pfizer brought the first ever ADC to the market for patients with leukemia — since then, only 13 ADCs have gained U.S. approval. But as the technology advances, new candidates are poised to make a bigger difference for patients with cancer and drive further biopharma M&A.

Mersana Therapeutics is one of the smaller players bringing ADCs to the forefront with their closest treatment in phase 3 clinical trials for ovarian cancer. The company plans to unveil the results of the study in mid-2023 and is aiming to file for approval around the end of the year. And ADCs have improved over time, said Mersana CEO Anna Protopapas.

"In the beginning of the ADC period, people believed that one size fits all — but in the body of evidence we've generated, we very much believe that one size doesn't fit all," Protopapas said. "You need new platforms that address the limitations to customize the ADC for a given target."

For Mersana, the Seagen deal is confirmation that ADCs hold high value.

"Ultimately, we're all in this business to make a difference for patients, and that has been the success of Seagen that the rest of us are following," Protopapas said. "And we believe the next wave of technologies and products can make a difference for patients."

Collaborations galore

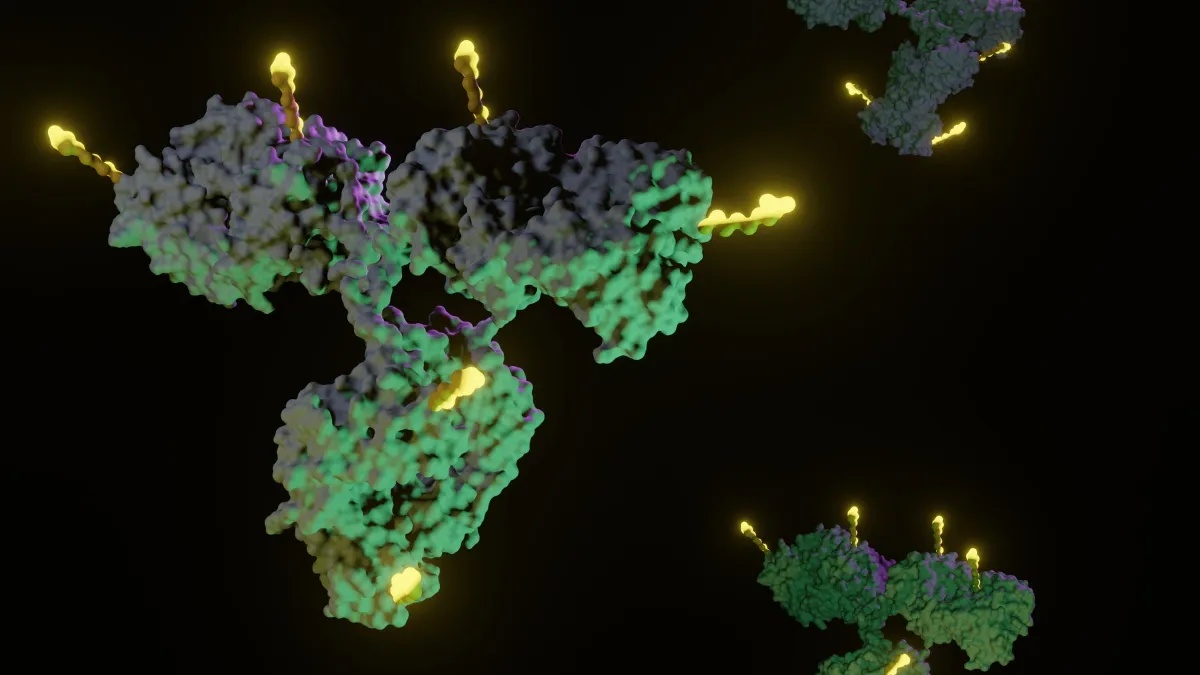

ADCs combine a cancer drug with a targeted antibody — and like that potent pairing, companies with a strong platform are collaborating with pharmas that have complementary expertise and products. Seagen, for instance, has teamed up with pharma giants like Merck & Co., Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb and Abbvie, among others.

Similarly, Mersana has ties with Janssen, Merck KGaA and GSK to bring their ADCs to market.

"We built these platforms that can be applied to many different targets — more targets than we ourselves could develop into products as a small company," Protopapas said. "So what our partnerships allow us to do is leverage the expertise and resources of partners to bring more of our ADCs into the clinic and hopefully, eventually, on to patients."

Mersana entered into the Janssen partnership just over a year ago — the company sends Mersana their targeting antibodies to create different ADCs, and Janssen can then investigate each one to find the right combination. That partnership is still in the discovery phase.

Mersana is also tinkering with the ADC process by making new kinds of conjugates. Typically, ADCs carry a cytotoxic payload to kill cancer cells. But one of Mersana's candidates — XMT-2056, in development with GSK — instead carries an immunostimulatory molecule that would kickstart the immune system to fight cancer.

Tragically, a patient in the phase 1 trial died and the FDA has placed a hold on further trials until an investigation takes place. Protopapas said the company is working with the regulator to find a way forward.

"It's a very exciting area and obviously the preclinical data was promising, but we're charting new ground here," Protopapas said. "We want to make sure we move forward in a safe and scientifically rigorous way."

Despite the delayed trial, Protopapas said that expanding the ADC arena to broader applications could open up the field for better therapies.

"There are a lot more resources going into the field from the bigger companies, and we know that the more resources targeted to new platforms, the more significant they can become," Protopapas said.

The value prospect

New modalities like ADCs form the backbone of biopharma M&A and are likely to continue sparking new deals, said EY global deals leader for life sciences Subin Baral. Even though 20 years is a long time to wait for a modality like ADCs to mature, that confidence has led to deals like the $43 billion Pfizer-Seagen marriage.

"The confidence level of these modalities generally takes a long time to materialize — I believe that ADCs are now at that point where they are taking center stage," Baral said.

Bigger biopharma players and those with cash are paying attention, particularly as older brands face the loss of patent protection.

"We're seeing a lot of the venture capital funding going into the ADCs, and from our perspective, while we have been saying this for quite a number of years, the new modalities are a way of getting access to new revenue streams for big biopharma companies facing the patent cliff and with revenues potentially at risk."

Investments in ADCs, as well as gene therapies, antibodies and peptides made up about 52% of private equity and venture capital in biopharma in the first quarter of 2023, EY said in a report. The Seagen acquisition was a confirmation of the importance of the space.

Baral likens the ADC revolution now to what cell therapies like CAR-T were a few years ago. Gilead, for instance, made a major move in 2017 to buy Kite Pharma for just under $12 billion, and J&J inked a major collaboration with Legend, another CAR-T player.

"There aren't that many quality assets that are available in the market, and biopharma companies don't have enough R&D in their internal pipeline to be able to replace some of the revenue at risk," Baral said. "So the question now is, what else do I start looking at?"