Welcome to Biotech Spotlight, a series featuring companies that are creating breakthrough technologies and products. Today, we’re looking at American Gene Technologies and its “software development” approach to developing gene therapies.

In focus with: Jeff Galvin, CEO, American Gene Technologies (AGT)

AGT’s vision: After a brief retirement from the tech sector in the early 2000s, Galvin founded AGT with the goal of harnessing genetic medicine to develop a one-dose functional cure for HIV and other diseases. He also sees the company filling a niche in the gene and cell therapy world as a sort of “software developer” with a platform of reusable components from which its therapies are developed.

“Nobody's really focused on the middleware (in cell and gene therapy development),” he said. “My whole concept was gene and cell therapy is so broad, and it's so much like the software industry, that the most important thing to do is develop these middleware components that you can mix and match to create efficiencies and that you can later leverage when the market is ready, when pharmas are ready (and) when the FDA is ready.”

Its strategy: Over the last 15 years of developing its HIV therapy, the company has patented 25 processes — from how it isolates certain T cells to its lentivirus viral vectors — that Galvin believes could be “valuable building blocks that will eventually be in 1000s of drugs” either developed by AGT or at other companies licensing AGT’s technology. That side of the business is still growing, he said, noting that AGT has mainly “been approached by “really small companies without any money” for such deals.

Many biotech companies are built on similar types of platform technologies, but Galvin argued that AGT’s component-focused approach is different. Other companies typically “do one thing,” he said, whereas AGT’s platform approach includes smaller components that build into an entire proprietary operating system, like Apple’s patented iOS.

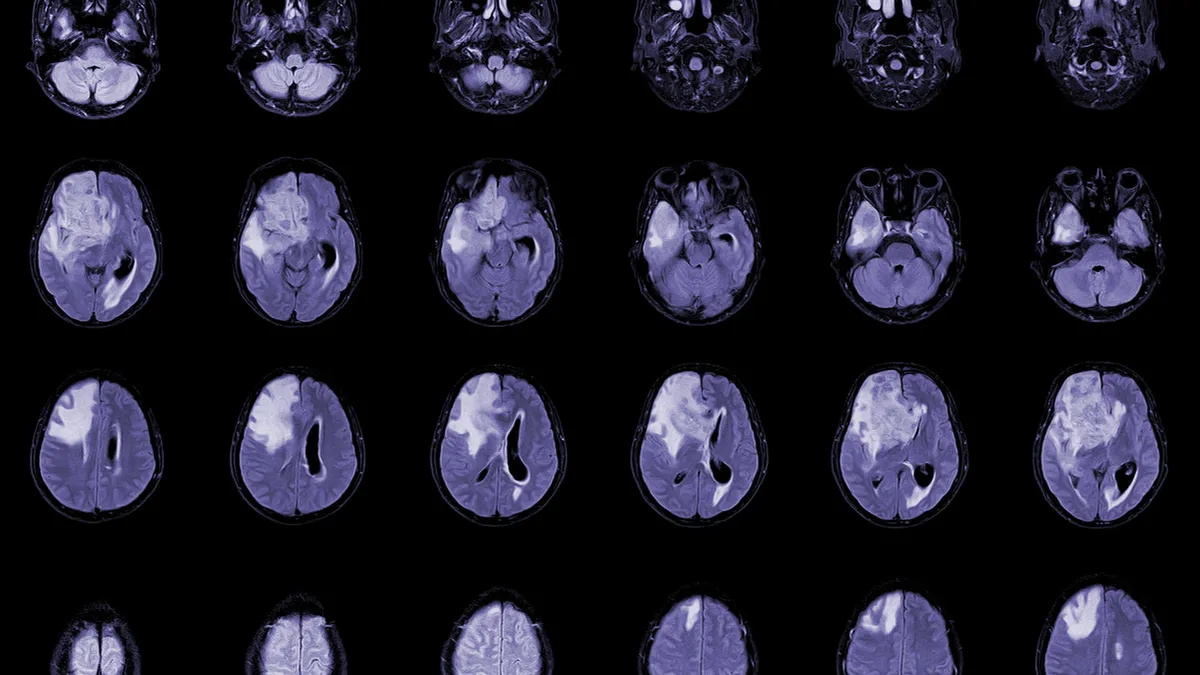

At a glance: In a recent phase 1 trial of seven patients, the company’s HIV candidate AGT103-T, met primary and secondary endpoints. The drug, a single dose autologous cell therapy, uses a lentivirus vector to deliver modified HIV-specific CD T cells, which is a type of white blood cell that is often depleted in HIV patients. If effective, it could reduce the depletion of CD4 T cells and restore the body’s ability to kick-start an antiviral immune response to naturally control HIV.

“We pulled those out and we can modify them with viruses, so they are impermeable. Now (the cells) can survive the HIV attack (and) stick around and do their job. When they do their job, then they can clear HIV just like you clear a cold,” Galvin said of the approach.

The company is in the midst of an analytic treatment interruption study which takes patients off their regular antiretroviral therapies to better gauge the efficacy of the cell therapy in suppressing HIV. It’s also in talks with the FDA over protocols for a phase 2 trial, which Galvin said will enroll 24 patients.

AGT is also conducting preclinical work on a drug to treat the rare, inherited monogenic disease phenylketonuria, as well as an immuno-oncology program, dubbed ImmunoTox, to deliver therapy to solid tumors using lentiviral vectors. Down the line, Galvin sees potential for treating a range of monogenic diseases.

Why it matters: Existing antiretroviral therapies for HIV allow patients to live fairly normal lives and, when taken every day, can act as a functional cure by bringing the viral load so low that it cannot be transmitted or progress into AIDS. But an actual one-and-done functional cure has remained elusive for drug developers since HIV was first discovered more than 40 years ago.

One of the latest attempts at a cure was with an anti-inflammatory antibody in 2018 that proved successful in monkeys but failed to show any efficacy in humans. Since then, many HIV trials have focused on developing a prophylactic vaccine for the virus. AGT is one of just a few companies, including Gilead, working on a functional cure for the virus. Currently, Gilead has several ongoing proof-of-concept studies testing new therapy combinations to tackle the virus in novel ways.

If validated, AGT’s therapy could provide a more convenient option for HIV patients to manage their disease, and could decrease the stigma of regular dosing, Galvin argued.

“We're making a cell therapy that would take somebody who has HIV, and it would suppress it for life in a way where they wouldn't need any medication,” he said. “They (would) go from daily medication or whatever type of regimen they're on for viral suppression to essentially living a normal life.”

However, there’s a long list of promising HIV cure strategies that, in the end, yielded no results. And although AGT’s therapy is one of the most advanced candidates at the moment, it still faces a long road ahead before it can be clinically validated.

AGT’s progress

When Galvin, who spent his early career as a Silicon Valley software engineer turned marketing executive at the likes of Apple and Hewlett-Packard, founded AGT, he saw parallels between gene therapy development and the tech industry.

“We're making a cell therapy that would take somebody who has HIV, and it would suppress it for life in a way where they wouldn't need any medication."

Jeff Galvin

CEO, AGT

“Coming from the software industry, I had an immediate epiphany,” he said. “I was like wait a minute, viral vectors are diskettes for the organic computer, the human cell. Now that we can modify your operating system, your DNA, what can’t we do?”

He created AGT to develop cures and the elements of cures that other scientists could build from, in the vein of major companies like Apple and Microsoft.

“I thought, somebody is going to be the Microsoft of this business one day,” he said, noting that many people build software using Microsoft’s operating system. “I took my whole retirement, dumped it into starting this company. It was a really perilous journey for 10 years.”

Now, based on phase 1 data from the company’s first trial of its autologous gene therapy for HIV, Galvin said he believes that the “journey was not in vain.”

In the case of the phase 1 study in which patients have stopped taking antiretroviral treatment, Galvin admits that aspirations were somewhat subdued because when a gene therapy is administered in combination with antiretrovirals for a prolonged period of time, the body sheds the unnecessary immune cells created by the therapy. So far, however, three of the seven patients tested in the study showed “significant suppression of their virus without antiretrovirals,” and one patient’s virus remained undetectable six months after.

“This was a really good finding, considering that the number of cells in (the patients’) bodies by the time we took them off antiretrovirals was only 2% to 5% of their original (count),” Galvin said.

The next step will be much more telling, though. In a phase 2 study, AGT hopes to be able to conduct the analytic treatment interruption earlier after administering the treatment — at 14 days, 30 days and 60 days — to see if the efficacy improves.

“We also want to gather more data from these 24 patients to see if we can find a correlation between aspects of their disease and the outcomes, because if we find that a subgroup gets cured, that's a drug,” Galvin said. “That would be a sustainable business model if that group is 3% of the population or better.”

Several challenges also remain. For instance, taking patients off antiretrovirals poses the risk that they may develop a new strain of HIV and that old drugs will no longer work to treat them. It will require close monitoring, ensuring that the disease doesn’t “run amok,” and putting patients back on antiretrovirals if their viral loads increase too much, Galvin said.

Another issue is funding and pricing dynamics. Though investment in cell and gene technologies has picked up in recent years as more therapies are approved by the FDA, it remains a fairly nascent space.

“I think that the major challenge in what we're doing is that gene and cell therapy is really new and historically, let's say over the last 10 years, there hasn't been a lot of interest in it,” Galvin said of AGT, which raised $69 million in its first six rounds of financing, according to Andrew Miller, AGT’s vice president of finance.

“The key is that we were able to go wherever the science took us because we are not a VC-backed company,” he said. “A technology company just goes as fast as they can, (while) a visionary company is in it because they believe it is going to lead to something great. That is what AGT is attempting to do. This place reminds me more of Apple than any other company I’ve seen.”