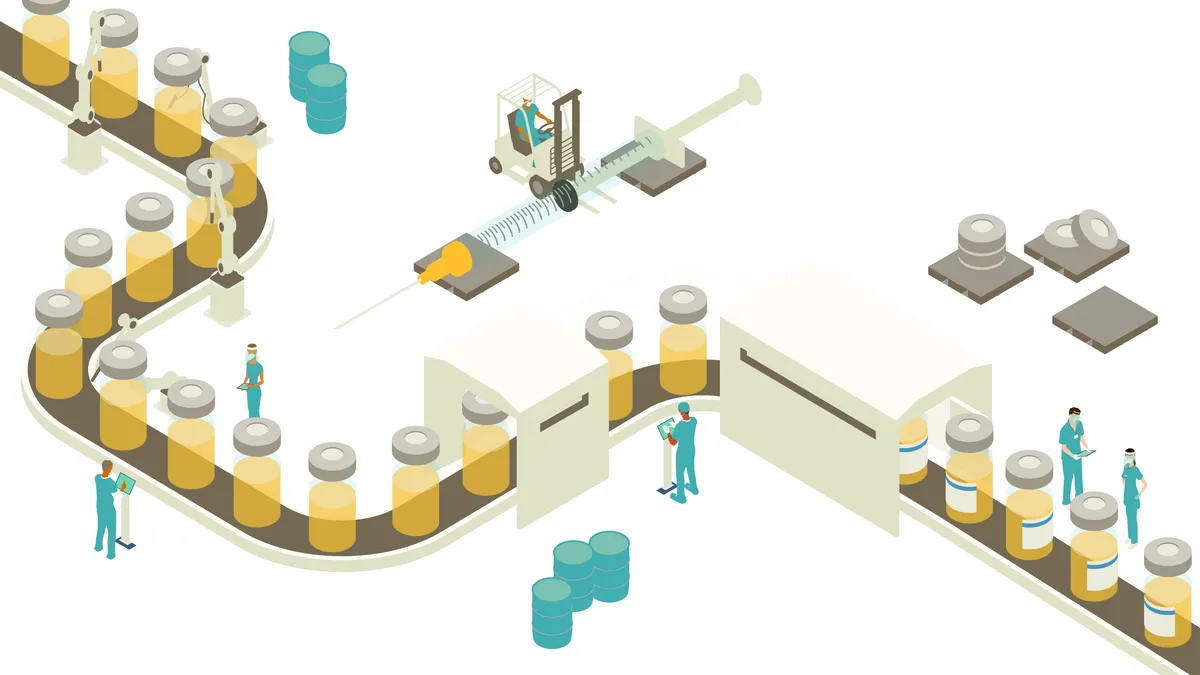

*Solutions that encompass the strategy, processes, people, technologies, and resources responsible for ensuring the flow of materials and services are necessary to deliver an organization’s value to its end-user customers.*

MANAGING INVENTORIES, WORKING CLOSELY WITH CONTRACTED SUPPLIERS TO ENSURE DELIVERIES, AND ENSURING THAT HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS HAVE PREFERRED MATERIALS ARE ALL CRUCIAL,BEHIND THE SCENES ELEMENTS TO A COMPANY’S SUCCESS. And, by managing inventory more effectively, companies can increase the odds of holding on to their most valuable asset — their customers.

That link is now understood by many industry leaders, and the industry’s approach to managing operations is changing. No longer does it apply simply to the manufacturing of products, but also to managing a supply chain — spanning suppliers’ suppliers to customers’ customers. Effectively configuring a company’s supply chain can be a source of sustainable competitive advantage, and can significantly impact the bottom line.

Pharmaceutical organizations that have been successful in managing their supply chains have a few traits in common. They often make structural or organizational changes that add directly to the company’s profitability. They involve the marketing and sales department in logistics early on in a product’s launch. They create partnerships with suppliers and customers. They capture relevant data and track performance of their distribution systems. And they put their best people in the departments that oversee a coordinated distribution network.

SUPPLY CHAINS — THE WEAK LINK

Unfortunately, managing the supply chain hasn’t gotten the attention it deserves. More often than not, the various departments within a pharmaceutical company work in a silo, with little emphasis or incentives provided to coordinate activities that could lead to supply-chain efficiencies. For example, a purchasing manager who is motivated to get the lowest cost for what he or she purchases may end up stockpiling unnecessarily high inventories. Or a transportation manager may look to receive the lowest cost, but choose an option that could delay delivery to consumers or be detrimental to inventory.

“The supply chain continues to be an area that I would characterize as being mismanaged by most companies,” says Russell Hagey, managing director of healthcare/biotech industry at Bain & Company Inc.

“Industries in general have not focused their attention on supply-chain management as a source of either profit or competitive advantage. Most companies say managing the supply chain is a priority, but we find that only 10% to 15% of companies truly have all the information they need about their company’s supply chain.”

*side profile* – Most companies say managing the supply chain is a priority,but we find that only 10% to 15% of companies truly have all the information they need about their company’s supply chain. RUSSELL HAGEY

The pharmaceutical industry is not alone in its inability to adequately assess these networks. A recent study by Bain & Co. found that only 33% of companies across all industries correctly measure supply-chain performance. More than 85% of senior executives say improving their firms’ supply-chain performance is one of their top priorities, but fewer than 10% are adequately tracking that performance. And fewer still — just 7% — collect the information necessary to meaningfully measure progress.

In Bain’s survey of various industries, most companies, those with average management of their supply chain, spent 9.8% of revenue on these functions, while the top performers spend 4.2% of revenue.

Mr. Hagey says companies that are successful in efficiently managing the supply chain can outperform their competitors.

“The delta between companies that are very good at supply-chain management and those that are average continues to increase,” he says. `”Companies that do supply-chain management very well often have a 2to1 advantage in terms of cost position in the supply chain. And that advantage, we believe, translates into real profitability and real dollars that can be reinvested into development of other areas that would drive value.”

Pharmaceutical companies are trying to get a handle on where the costs — and the savings — really lie with regard to the supply chain. Companies are working to track performance along the entire supply chain continuum.

“Historically, evaluation of the supply chain has been based on hunches or intuition,” Mr. Hagey says. “This is not at all dissimilar to how pharmaceutical companies evaluated time-to-market, R&D, and development times 10 years ago. We’re seeing the best companies now trying to develop data and metrics around their supply chain, just as they did with R&D 10 years ago.”

But recent attempts to implement successful supply-chain initiatives from other industries have not worked well in healthcare. One supply chain initiative was to employ the concept of ECR, efficient consumer response, to pharmaceutical distribution. This effort, which originally began in the grocery industry, emphasizes meeting the needs of the end consumer as a way to identify opportunities for improvement.

Despite the promise of ECR, it has done little to improve the management of inventory, says Sean O’Neill, principal with St. Onge Co. “A key reason for this situation is that large retailers continue to up the ante with respect to imposing severe line fill rate requirements on manufacturers,” he says. “Manufacturers would rather overstock products than experience financial penalties for noncompliance.”

Managing inventory, he says, is critical. The cost implications of holding too much inventory include tying up financial resources and increasing the potential for out-of-date stock.

Recent supply-chain initiatives, Mr. O’Neill says, have focused on how to get more out of existing distribution center and warehouse resources. Software companies have enhanced product offerings to include an “intelligent scheduling capability.” “These new software products are comprised of rules-based optimization engines and algorithms that sequence order release for execution in a manner that balances workflow, meets customer priorities, and maximizes resource utilization,” Mr. O’Neill says.

Successfully managing the entire discovery and research process is important as well, says Jamie Duke, VP of products, operations, and strategy at SciQuest Inc. “Process inefficiencies in the initial planning, sourcing, and discovery phases significantly impact delivery, slowing time to market, and ultimately resulting in lost revenue opportunities.”

*side profile* The leaders have leveraged the advantage gained from best-of-breed supply-chain technology to drive greater value from their ERP systems and widen the gap from their competition. GLYNN PERRY

THE WHOLESALER CONNECTION

Unique to the pharmaceutical industry is the sales role that wholesalers take on, says Adam J. Fein, Ph.D., president of Pembroke Consulting. “One of the strangest things that I’ve ever seen in this industry is that the marketing and the sales departments typically have relation ships with wholesalers. These departments fulfill the demand.”

Dr. Fein says there is often a communication breakdown in this system, not as might be expected between the marketing department and wholesalers, but between operations and manufacturing.

“The operations people in wholesaler companies rarely communicate with the operations executives in the manufacturing world,” he says. “Many manufacturers view distributors as merely their outsourced fulfillment and marketing arm. I think one of the greatest opportunities going forward is for the operations and the logistics executives of the pharmaceutical manufacturers to get more involved with the senior executives of the pharmaceutical wholesalers.”

He emphasizes that despite this lapse in communication, the wholesaler model is an efficient distribution system.

“This is one of the most efficient channels of distribution that I’ve seen,” Dr. Fein says. “Pharmaceutical wholesalers have operating expenses that are a fraction of what distributors in other industries have. That means they are a low-cost fulfillment channel for manufacturers. As a result, the majority of the margin owned by wholesalers for performing distribution functions comes from manufacturers in the form of discounts, rebates, and forward buying opportunities.”

Pharmaceutical distribution is a growing business. Sales have more than tripled since 1991, rising from $33.3 billion to $126.3 billion in 2001, according to the Healthcare Distribution Management Association, a trade group representing wholesalers/distributors and manufacturers of pharmaceutical and health-related products and information (see related box on page 32). The group says using a wholesaler or distributor has many benefits, including lowering distribution and shipping costs, maximizing product accessibility, and establishing systems for new product introductions, electronic order capabilities, and product recall assistance.

What Dr. Fein says is inefficient is the chargeback system, which creates a great deal of complexity in the supply chain.

“Essentially, chargebacks occur when the manufacturer and the customer are negotiating the price that is discounted off of the list price,” Dr. Fein says. “Then the wholesaler is, in essence, charging back that difference to the manufacturer. The maintenance of the system creates a whole range of inefficiencies.”

Technology has automated this somewhat, but there is still some friction in the channel.

“I don’t know if there is a simple way to solve this because it would require everyone to change behavior at once,” he says.

****Can Electronic Records Help?

One of the biggest bottlenecks in managing the supply chain in the pharmaceutical industry is the immense administrative burden of a paper-based documentation and work process. Because of the need to meet stringent quality regulations, pharmaceutical companies have a tremendous amount of paperwork that must follow a product batch.

“While other industries can focus on just-in-time component delivery and en-route assembly to eliminate bottlenecks, the pharmaceutical industry has to provide an immense focus on accurate internal and external documentation,” says Marcus Yoder, director, life-sciences industry, at Agile Software Corp., which provides a Web-based solution to help manage the product record. Complicating the issue is that pharmaceutical companies often use multiple information technology systems to manage their supply chain, says Doug Souza,VP of process manufacturing and configuator development at Oracle Corp.

“Currently, the biggest struggle is that companies have to get their own systems in order to properly communicate with suppliers and customers,” Mr. Souza says. “When a software system is implemented in a pharmaceutical or biotechnology company, it has to be validated so that it meets all the requirements of the Food and Drug Administration for running a GMP system. Companies spend a lot of money making sure their systems are up and running and properly validated.”

One answer, Mr. Souza says, is the use of electronic records systems, which can help save money, reduce the amount of paper that flows through an organization, and ease FDA audits.

In 1997, the FDA released the final rule, 21 CFR part 11, for accepting electronic records and electronic signatures on various documents.While the use of electronic records is not mandatory, those companies that rely on electronic information instead of paper records must meet the criteria outlined in this rule.

Oracle has developed software that allows life-sciences companies to do their processing using electronic records and electronic signatures.

“Instead of having a paper document that follows the batch, a company can now have it signed electronically and be able to maintain that paper work electronically for faster inquires,” Mr. Souza says. “If a company undergoes an audit by the FDA or has a recall, it can go directly to the electronic record and within minutes find the lot numbers and raw materials contained in that product.”

Can electronic files save money and eliminate the paper trail?

“At Oracle,we have a paperless environment,” Mr. Souza says. “I manage a staff of 150 developers and I don’t see paper purchasing requisitions, POs, or expense reports. All of this is done electronically.”

To make this effective companies need to implement workflow procedures.

“We’ve been able to cut down our accounts payable costs significantly because we don’t have to have administrative people retyping in paper documents,” Mr.Souza says.”All the data are backed up in the database. There is no need for paper records.”

******

While the use of wholesalers can be an efficient system, it also can present challenges for tracking value in the supply chain.

“Wholesalers traditionally make their money by speculating on price,” says Jim Prendergast, partner, pharmaceuticals and life sciences practice at IBM Business Consulting Services. “They will spend a lot of time and effort deciding when a pharmaceutical company is going to increase its prices and they buy a lot of product before that. That creates a lot of demand variability that’s not real in the supply chain.”

Mr.Prendergast says pharma companies often experience high sales, say, for the first three quarters of the year and then see zero orders in the last quarter because there was a price increase at the end of the third quarter.

According to a study by Best Practices LLC, companies with effective supply-chain management systems select suppliers that meet various criteria that go beyond traditional cost per unit considerations, thus effectively reducing inventory errors and lowering costs in their supply chain. According to Best Practices’ research, by working together across the supply chain, these companies are able to pool talents and resources, yielding substantial gains in cost, quality, flexibility, system responsiveness, and overall performance.

Many of these companies view their relationships and methods of interacting with their suppliers as one of the few advantages they have over their competitors.

Increasingly, pharmaceutical companies are viewing their supply chains as a high and growing strategic priority, says Colin MacGillivray, director of Inforte’s life-sciences practice. Inforte is a customer relationship and demand management consultancy.

“Pharmaceutical companies are faced with greater price pressures and increased R&D costs, which are squeezing margins,” Mr. MacGillivray says. “Supply-chain performance is becoming more crucial to sustain earnings.”

Mr. MacGillivray says this is a change from years past, when favorable pricing and demand ensured high-quality earnings for shareholders irrespective of supply-chain performance.

“The traditional industry emphasis on `never stocking out a product’ means many clients have built excessive capacity and high levels of inventory,” he says. “These are lucrative targets for cost reduction in today’s business environment.”

LINKING MARKETING AND SALES

Companies that are particularly good at measuring the value of their supply chains have worked to bring the marketing and sales department into discussions about distribution and logistics early in the process. This allows manufacturers to build relationships with customers and accurately forecast demand.

“To me this makes all the sense in the world,” says Peter Wester mann, senior VP of business development for UPS Supply Chain Solutions. “The entire product team is interested in not only who the company is selling it to, but the whole process of how the product physically gets to the market. As time goes on, we will see marketing departments at more companies become involved in buying decisions.”

“Today, marketing and sales are much more intertwined with logistics than they were 10 years ago because the logistic demands and customer demands have become much greater,” says Dr. Tan Miller, director of logistics for U.S. distribution and team leader for consumer distribution operations at Pfizer Inc.

“If a company wants to run a sensible logistics operation, it really has to closely align sales and marketing so that it can better understand the demands today and what the demands will be two and three years from now,” Dr. Miller says.

This process can provide the company’s marketing department with data about what product is selling, at what price point, and how quickly it is moving off the customer shelves, Mr. Hagey says.

“What we find is that the best pharmaceutical companies get both organizational alignment, incentive alignment, and information alignment end-to-end, from purchasing to the customer shelves, whether that is the physician’s office or the local pharmacy,” Mr. Hagey says. “Those are the companies that can then take a lot of cost out of their supply chain because they have information throughout that chain. They also have an organization that is speaking the same language.”

This, however, has been easier to implement on the consumer side of the business, where pharmaceutical customers are large retailers, grocery channels, and mass merchandisers.

As Dr. Miller points out, there is much that companies have to do to make this concept a reality on the pharmaceutical side of the business.

“One of the differences on the pharmaceutical side is that there is a lot more distribution that takes place through wholesalers,” Dr. Miller says. “When a company is dealing with a wholesaler, the wholesaler may handle some of the logistic activities that the manufacturer would have to handle if it were going directly to the customer.”

STRENGTHENING THE CHAIN THROUGH TECHNOLOGY

Best Practices has found that companies with the most effective supply chains use technology to improve their supplier partnerships.

Dr. Fein says the pharmaceutical wholesale supply chain is one of the most IT intensive supply chains that he’s worked with.

“The wholesalers in this industry have applied technology far beyond the level of almost any other distribution channel,” Dr. Fein says. “As a result, the percentage of manufacturer distributed products has dropped from about 50% to less than 10% today. Technology has allowed pharmaceutical manufacturers to focus on what they do best — drug discovery and commercialization.”

According to AMR Research Inc., companies are increasing their spending on information technologies for supply-chain management. The firm’s SCM Application Spending Report, 2002-2004 reports that the driving theme in 2003 for users regarding supply-chain application investments is improved fulfillment capabilities that utilize technology with the flexibility to support multiple workflows and rules.

The report found that major business initiatives driven by customer focused strategies are creating supply-chain opportunities, and that the penetration of users using at least one module of supply-chain management increased to 46% in 2002. Order management and inventory management continue to be the most frequently used supply-chain management modules, implemented by more than 85% of companies interviewed with supply-chain management software.

The pharmaceutical industry, according to AMR Research, currently spends 5% of total company revenue on information technologies, which is above average for all vertical markets measured by the study.

AMR states the pharmaceutical industry plans to increase IT spending in 2003 by 5%. Much of this increase has been in response to FDA regulations, specifically the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). The 62% of pharmaceutical companies planning to increase their 2003 IT budget by 3% are looking to maintain growth while bringing new products to market; IT investment therefore will be associated with clinical trials and customer management to increase the speed of new products to cash cycles.

******Distributions Amid Mergers: Pfizer’s Experience

What could be more challenging than trying to integrate two large-scale distribution and supply-chain networks? Pfizer Inc. already has been through one such effort, when it acquired WarnerLambert in June 2000, and is about to embark on another after its acquisition of Pharmacia Corp. is completed.

“The overall process is challenging to merge,”says Dr.Tan Miller, director of logistics for U.S. distribution and team leader for consumer distribution operations of Pfizer Inc. “When two companies become one, as soon as possible it wants to be able to present one unified face to the customers.”

Dr.Miller says Pfizer’s philosophy is to do its own distribution — and to have an entire product line being sourced to the customer from a single distribution center as quickly as possible after a merger.

“We want to house the entire pharmaceutical product line in single facilities, and that doesn’t mean just one distribution center for the whole country,” he says. “This involves an awful lot of movement of goods and modification to existing infrastructure. And that is just the physical distribution and warehouse management side. There is a whole customer relations/customer service/customer order service management side as well.”

Integrating differing technologies can present other obstacles, Dr. Miller says. Even though Warner-Lambert’s technologies were similar, he says there was enough of a difference in system levels and approaches that a major element of integration was making sure that all systems and the technology interfaces that were required would work.

“One challenge is that nomenclature could be different, ship dates or inventory available dates are some things that can be different from system to system and company to company,”he says.

Warner-Lambert also used different vendors for transportation.”This involves getting a handle on the total set of vendors that are being used, deciding what vendors and transport modes make the most sense going forward, and putting together a strategy that aligns around the selected key vendors that work for the merged company.”

While addressing short-term issues of integrating what can be two very different distribution networks, it’s important, he says,not to lose sight of the longterm goals of the organization.

According to Dr. Miller, companies have to evaluate whether steps put in place at the start are logical, or are they decisions that serve the short term and possibly constrain a company’s ability to operate in the long run.

“Very often, a company cannot immediately make the changes that are necessary for where the organization is going to be five years down the road,”Dr. Miller says.

******

AMRResearch asked study participants to provide details on their IT budget allocations. Companies were provided with eight categories into which to assign their IT dollars: hardware, networking, applications, soft ware infrastructure technology, outsourced services, security, business con tinuity, and head count/training. The current allocation of the IT budget flows from the necessary building blocks to the overlying tools that hold it all together. For healthcare, according to the survey, one-quarter of the IT budget is allocated to hardware and 21% to applications.

Technology projects often involve the deployment of enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, which have led to improved product forecasts modeled from historical data in time, product, and position. According to AMR Research, the pharmaceutical industry in 2002 spent 27% of its enterprise application budget on ERP systems.

ERP systems have the potential to integrate and streamline manufacturing plants, distribution centers, procurement, and other back office operations, which is likely to gain importance if electronic commerce, genomics-driven mass customization, continual price pressure, and industry consolidation prevail, according to Urch Publishing, a consulting and business information company. Companies with enterprise integration can make major reductions in inventory costs, significantly improve customer services, and boost quality.

According to an April 2001 report by Urch Publishing, despite considerable investment in ERP soft ware, many pharmaceutical companies have not achieved the synchronized and efficient supply chains they were hoping for. The report concludes that companies are using ERP systems to support traditional supply chain, manufacturing, and procurement functions rather than to facilitate new ways of doing business that will be necessary in the global marketplace of the future.

Developing reliable and accurate forecasting models and metrics will be critical for pharmaceutical companies going forward.

“Our clients are selling larger numbers of products with shorter commercial lives in a larger number of product configurations through a greater number of channels,” Mr. MacGillivray says. “The ability to integrate this complex information into unified demand forecasts is essential to better use capacity and drive cost savings. This forecast information is the bedrock from which companies can plan achievable production and distribution plans to get the right amount of product to the right place at the right time.

“Improving the forecasting function is more than a technical problem,” Mr. MacGillivray continues. “Our work with clients also addresses the training, metrics, and organizational changes needed to ensure these technologies deliver on the benefits promised.”

According to Mr. MacGillivray, flexibility is growing in importance as manufacturing and fulfillment operations involve a larger and ever changing mix of partners across supply chains that are increasingly global.

“It is increasingly important to be able to change production volumes quickly and cost effectively in response to changes in demand around key events,” he says. “These events may include product launches, the introduction of alternative products by competitors and/or the introduction of a new regulatory requirement. This supply chain flexibility is increasingly critical to competitive success.”

“Most companies only have focused on the basics and, as a result, have formed manual supply-chain planning processes,” says Glynn Perry, VP of life sciences at Manugistics Group Inc., a provider of supply-chain software solutions. “Since the processes they’ve developed are typically very labor and time-intensive, these companies are constrained by the time associated with planning, which ultimately hinders their ability to be nimble and anticipate change.”

He says companies are missing opportunities to create improvements in inventory, operations, and customer-service.

“The leaders have leveraged the advantage gained from best-of-breed supply-chain technology to drive greater value from their ERP systems and widen the gap from their competition,” Mr. Perry says. “Using this technology, they have been able to tackle such complex challenges as expiration dating, lot tracking, and other regulatory issues. And today, the leaders are extending their advantage by collaborating with their external business partners and unifying the supply chain under one umbrella planning system, functionality typically not provided by even the most advanced ERP systems.”

Dr. Miller points out, however, that the problem isn’t a lack of data. “In general, there is more and more data available about what’s going on with in and across the supply chain, such as point-of-sale data and inventory data. A challenge everybody faces is how to effectively utilize and integrate this data into information that will really help a firm make more sensible decisions. As a firm, we need to figure out what makes sense and what to focus on to help drive sensible manufacturing. It’s not an easy thing to do.”

According to Mr. Duke, comprehensive materials management in most pharmaceutical and biotech companies is either nonexistent or so fragmented that it’s difficult to get a comprehensive understanding of the inventory available within an organization.

“It’s not uncommon for data about proprietary substances to exist in a spreadsheet in one lab professional’s desktop computer, but be unavailable to his or her colleagues,” he says. “Because they can’t accurately track their materials, firms end up wasting valuable time and money synthesizing entities that are in stock in the lab next door.”

“Technology clearly matters,” Mr. Hagey says. “Our experience, however, is that companies tend to think technology is a panacea that will solve all their ills. They implement technology solutions before they get a range of other things right. The companies that do supply-chain management best view technology as an enabler. They get the segmentation right. They get the metrics right. They get the strategy right. Then they put the technology in place to correctly manage all these functions."

The best companies manage their supply chain, their customers, and their products differently depending on the end-user, Mr. Hagey says.“That differential management function segments the customer base and manages each uniquely," he says. “By doing that segmentation, a company can react much more specifically to a set of needs, and can get a better value proposition. And this tends to give the company a better cost position and better pricing."

Many companies, he says, manage their different supply chains the same way. They ask all vendors to deliver on the same terms. They ask for all products to be stocked the same way at all locations. They have a consistent process.

“But that doesn’t account for each different channel — whether it isa physician office or a hospital or a pharmacy— those customers have different needs," Mr.Hagey says. “Some drugs sell faster than others. Some have a higher value than others."

Mr. MacGillivray says successful companies plan the technology aspects of their relationships before entering into any alliances.

“Technology is not the complete story, and it is important to have a coordinated approach to outsourcing that includes people, business processes, and metrics alongside technology in a fully integrated way," Mr. MacGillivray says. “We have observed some cases where outsourcing relationships have been considerably more painful than needed because technology has not been adequately planned in advance."

Mr. Westermann says improvements in technology are allowing the buyer and the seller to be more closely connected.

“An evolution to a more direct buy-sell relationship will continue to emerge," Mr. Westermann says. “I’m not saying there is going to be revolution. The distributor model that exists in the pharmaceutical and medical/ surgical industries today isn’t going to vanish. As products become more specialized, there will need to be numerous strategies within the portfolio. And sellers are going to want to be able to learn more about their customers by examining their buying and selling supply-chain patterns."

******SUPPLY-CHAIN QUICK STATS

INDUSTRY GROWTH

Sales in the pharmaceutical and healthcare products distribution business has more than tripled since 1991 — rising from $33.3 billion to $126.3 billion in 2001. In addition to traditional healthcare product distribution, wholesalers are acquiring and creating companies and/or subsidiaries that provide other related services to their suppliers and customers — serving the entire healthcare supply system. These services range from pharmacy automation to private label packaging and information systems. (The sales from these new businesses are not reflected above.)

AVERAGE SALES PER DISTRIBUTION CENTER

The composite average of HDMA member distribution center sales was $689 million in 2001, with $5,481 of sales per square foot of warehouse space.

SKUS PER DISTRIBUTION CENTER

The median distribution center stocks nearly 22,000 items: about 51% are pharmaceuticals, 21% are nonprescription drugs, and the balance are health and beauty-care products, general merchandise, durable medical equipment, and home healthcare items. Stock turnover was 8 times for 2001.

PRODUCTIVITY MEASURES

In 2000, handling cost per invoice line was $2.70. In 2001, average order line extension was $110.61 (value of a line of merchandise).

OPERATING CHARACTERISTICS AS A PERCENTAGE OF TOTAL INDUSTRY SALES

Return on Net Worth: 6.71%

Gross Margin: 4.32%

Operating Expenses: 2.57%

Operating Profit Margin: 1.65%

Net Profit After Taxes: 0.72%

Source: The Healthcare Distribution Management Association (HDMA), Washington, D.C., is the trade association representing wholesalers/distributors and manufacturers of pharmaceutical and health-related products and information. HDMA’s active membership consists of about 72 companies operating 242 distribution centers throughout the Americas

*******

BIOLOGICALS — A KINK IN THE CHAIN

Specialized products include biologics, and new ways to get the product to the patient will have to be considered as more and more of these types of products reach the market. According to the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the research of biotech products has expanded greatly in recent years. Currently, there are 371 biotechnology medicines in various stages of development. By the end of the decade, biotech products could command about half of the $300 billion pharmaceutical industry, according to researchers at Kalorama Information.

Biologic products often are administered through injection or IV and have special handling requirements. These requirements undoubtedly will mandate that pharmaceutical companies adopt different distribution models to get these products to the patient in the appropriate fashion.

“The corner pharmacy usually doesn’t stock these items and with the extensive patient education component, a highly trained professional needs to guide the end user," says Jordan Karp, president of RxCrossroads, a reimbursement and distribution supply company. “Simply shipping a biotech product from a production facility to a distributor and finally to the pharmacy is not an option."

“The manner in which biological and biotechnology produced are introduced and ultimately distributed to physicians and patients, particularly with respect to new products, is increasingly viewed as a critical and strategic matter," says Ethan Leder, CEO of USBC. “Many manufacturers are teaming with distributors and specialty services companies earlier in a product’s launch cycle to most effectively impact the marketplace."

*****Experts on this Topic

AMR RESEARCH INC. Boston.; AMR Research is a strategic advisory firm that provides critical analysis and actionable advice to business and technology executives to help them manage resources, assess and mitigate risk, and increase business value. For more information, visit amrresearch.com.

JAMIE DUKE.VP of products, operations and strategy, SciQuest Inc., Research Triangle Park, N.C.; SciQuest provides technology, services, and domain expertise to optimize procurement and materials management for the life-sciences, industrial research, and higher-education markets For more information, visit sciquest.com.

ADAM J. FEIN, PH.D.President, Pembroke Consulting, Philadelphia; Pembroke Consulting is a management consulting firm assisting senior executives from market-leading wholesale distribution, manufacturing, and B2B technology companies. For more information, visit pembrokeconsulting.com.

RUSSELL HAGEY.Managing director, healthcare/biotech industry, Bain & Co. Inc., Los Angeles; Bain & Co. is one of the world’s leading global business consulting firms, founded in 1973 on the principle that consultants must measure their success in terms of their clients’ financial results. For more information, visit bain.com.

JORDAN KARP.President, RxCrossroads, Louisville, Ky.; RxCrossroads provides patient-focused integrated reimbursement and pharmacy services designed to meet the specialty marketing and distribution needs of the pharmaceutical, biotechnology and medical-device industries. For more information, visit rxcrossroads.com.

JIM PRENDERGAST. Partner, pharmaceuticals and life-sciences practice, IBM Business Consulting Services, Philadelphia; IBM Business Consulting Services manages initiatives — from strategic thinking to implementation. For more information, visit www-1.ibm.com/services/fullbusiness.html.

DOUG SOUZA. VP, process manufacturing and configuator development, Oracle Corp., Redwood Shores, Calif.; Oracle is one of the world’s largest enterprise software companies. For more information, visit oracle.com.

URCH PUBLISHING LTD. London; Urch Publishing provides essential business intelligence and information for management in biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and chemicals companies and associated businesses on a worldwide basis. For more information, visit urchpublishing.com

PETER WESTERMANN.Senior VP, business development, UPS Supply Chain Solutions, Alpharetta, Ga.; UPS and its subsidiaries provide an extensive offering of innovative transportation and freight, logistics, and international trade services for the movement of goods, information, and funds. For more information, visit ups-scs.com.

MARCUS YODER. Director life-sciences industry, Agile Software Corp., San Jose, Calif.; Agile provides product lifecycle management solutions used by companies to build better, more profitable products faster. For more information, visit agiles.com. gy and medical-device industries. For more information, visit rxcrossroads.com.

ETHAN LEDER.CEO, USBC, Washington, D.C.; USBC is a pharmaceutical services and specialty distribution company. For more information, visit usbioservices.com.

COLIN MACGILLIVRAY. Director, life-sciences practice, Inforte, Chicago; Inforte is a customer and demand management consultancy that helps clients improve customer interactions, revenue forecasting, and profitability. For more information, visit inforte.com.

DR. TAN MILLER.Director, logistics for U.S. distribution, and team leader for consumer distribution operations, Pfizer Inc., Morris Plains, N.J.; Pfizer, with headquarters in New York, discovers, develops, manufactures, and markets leading prescription medicines for humans and animals and many of the world’s best-known consumer brands. For more information, visit pfizer.com.

SEAN O’NEILL.Principal, St. Onge Co., York, Pa.; St. Onge is an accomplished engineering firm with experience in the design and project management of lean manufacturing facilities and high-performance distribution centers around the world with services that include logistics/supply chain strategy development, simulation, and network optimization. For more information, visit stonge.com.

GLYNN PERRY.VP, life sciences, Manugistics Group Inc., Rockville, Md.; Manugistics helps companies lower operating costs, improve customer service, and maximize revenue through a broad set of solutions tailored to the ethical drug cycle. For more information, visit manugistics.com.