BY ALEX ROBINSON

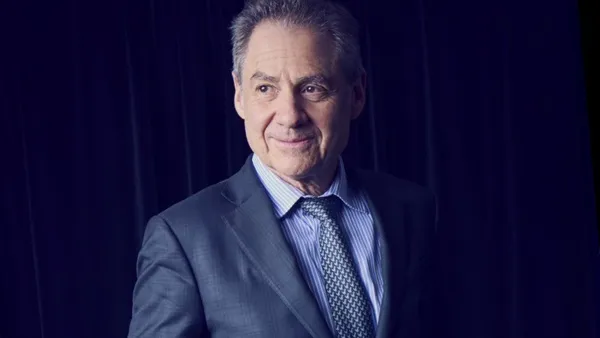

Let’s stop complaining about spending on prescription drugs,” Alan Holmer, president of the Phar maceutical Research and Manufacturers of Ameri ca (PhRMA) told an audience in April. “In fact, let’s hope that prescription drug spending goes up — not down.” Critics are quick to point out that spending on prescription drugs has eclipsed inflation. However, data show that the rise in pharmaceutical spending is primarily caused by an increase in the volume of prescriptions — which involves three overlapping trends: more new firsttime users of pre scription medicines, more current users taking medicines for longer periods, and more people (usually senior citizens) tak ing two, three, four, or more medicines at one time. Prescription drugs are just one part of the total healthcare equation. Policy makers and industry critics often focus on prescription drug prices, excluding the other components — hospitals, doctors, nursing homes, etc. These components need to be considered in concert, rather than as distinct entities. Despite an increase in prescription drug spending, Mr. Holmer states that today medicines account for only about nine cents of every healthcare dollar. In 1980, medicines accounted for less than five cents of each healthcare dollar; in 1997 the figure was seven cents. Nevertheless, many remain resistant to these increases, and Congress and many state leg islatures are moving, or have taken steps, to limit prescrip tion drug spending by suggesting price controls and weak ening intellectual property protection. Policy makers say the industry has to curtail increases in drug spending, but Mr. Holmer says they almost never talk about the other side of the equation. Without industry inno vation, which is fueled by costly research and development, patients would be deprived of the modern medicines, which were unavailable even a decade ago. Mr. Holmer notes that while the recent approval of a drug to treat sepsis is good news for anybody who gets the infec tion, it is “a cause for handwringing and nailbiting by some policy makers who seem to look at new breakthroughs not with awe, but with alarm. Because if there are wonderful new medicines available, patients will want them and doctors will prescribe them and, soon, we may be spending 15% or even 20% of our healthcare dollars on prescription drugs.” A report prepared for the Department of Health and Human Services notes that much of the increase in use and spending on pharmaceuticals has resulted from the introduc tion of new brandname drugs, some of which replace exist ing, less costly treatments and some of which help with con THE VALUEOF INNOVATION to increase as a result of more firsttime users of prescription medicines,more patients taking medicines for longer periods, and more people taking more medicines at one time. 32 S e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 2 PharmaVOICE VALUE of drugs A ditions for which treatment was not previously available. PhRMA points out that increases in prescrip tion drug spending represent a positive health care trend for Americans. And the National Institute for Health Care Management (NIHCM) industry association points to several mitigating factors that contribute to increased spending: new guidelines for use of pharmaceu ticals, greater treatment of underdiagnosed and undertreated patients, an aging population, greater attention to preventing and managing disease, and the replacement of older drugs with newer drugs. PhRMA notes that while drug spending continues to grow, it still remains “a very small share” of national spending. Aquestion of values Determining the benefits of newer drugs bal anced against their increased costs motivated Frank Lichtenberg, Ph.D., Courtney C. Brown professor of business at Columbia University Graduate School of Business and a research asso ciate with the National Bureau of Economic Research, to conduct an extensive study. Dr. Lichtenberg set out to test the hypothesis that, all other things being equal, a person’s health is an increasing function of the vintage of the drugs he or she consumes, where vintage refers to the year the Food and Drug Adminis tration first approved a drug. His overall conclu sion is that, in the aggregate, the benefits to soci ety of new drugs exceed their costs. One of these studies, which was published in Health Affairs, was based on data from the Household Component of the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, which surveys health care spending of noninstitutionalized U.S. citi zens. The data enabled Dr. Lichtenberg to com pute spending and charges linked with each condition, and to extrapolate other information, such as insurance status, the length of time a per son has had a condition, and the number of med ical conditions a person reports. Dr. Lichtenberg’s study, as updated recently with newly available 1997 and 1998 MEPS data, shows that using a newer drug — one that is five years old against one that is 15 years old — adds $18 in drug costs but reduces other medical costs by $129. Another study shows that the development, FDA approval, and use of new HIV drugs has played an important role in dramatically reducing HIV mortality. One additional HIV drug approval reduced the annual number of HIV deaths by about 6,100. And between 1983 and 1998, when there was an increase in the introduc tion of drugs and biological products to treat rare diseases, there also was a decrease in deaths from these diseases. The study shows that new drugs may also help people live longer. It estimates that the increase in the stock of drugs granted priority review status — drugs that are considered to offer a therapeutic advance over existing therapies — increased mean age at death by 4.7 months between 1979 and 1998, about 10% of the total increase in mean age during those years. Considering the increase in longevity and a value of $150,000 for a lifeyear, Dr. Lichtenberg says new drugs confer social benefit in the form of an annuity, after they reach the market, of $120 billion. Against this, he sets the estimated cost of developing 508 new molecular entities approved by the FDA from 1979 to 1998 at $182 billion. Overall, Dr. Lichtenberg’s study shows that in 1996 the increase in the number of drugs available between 1983 and 1996 cut by 12% the number of people unable to work, workloss days of those employed, restricted activity, and bed days of all people. “The general finding is that newer drugs are of higher quality than older drugs,” Dr. Lichtenberg says. “So people who have the opportunity to take these newer drugs for given conditions will be bet ter off in certain respects. These include increased longevity, higher quality of life or reduced activity limitations, and also reduced need for other kinds of medical care. Those are the benefits of newer drugs. But it is one thing to say people will bene fit more from new drugs than old drugs. The ques tion is: What’s the form of those benefits?” According to the study, these benefits take sev eral forms, which include improved health out comes, measured by a decrease in mortality and morbidity, and also decreased utilization of other medical services, particularly hospital care. Dr. Lichtenberg points out that his work makes no reference to particular drugs, classes of drugs, or diseases. “My work makes inferences about the general, the average, benefits that society realizes from new drugs,” Dr. Lichtenberg says. “Clearly, there is heterogeneity — some drugs deliver more ben efits of a particular type than others. For example, some drugs may have a much greater impact on mortality or morbidity, while others primarily improve quality of life or functional status or an ability to engage in activities such as work. But my research is about the average effect, not about the effect of a particular drug or disease.” A study released by NIHCM states that the incidence and prevalence of many chronic condi tions have increased in recent years. To the extent that more patients are being treated for chronic conditions such as diabetes, asthma, elevated cholesterol, and others is a positive trend for healthcare development. In the NIHCM study, cholesterolreducing drugs known as statins were ranked second in terms of contribution to overall retail sales growth between 2000 and 2001, a statistic that industry critics are quick to bring to light. According to a report from NDC Health, a healthcare information company, the number of patients taking cholesterollowering drugs was up about 7% in 2001, from 7.7 million patients to 8.2 million patients. New guidelines set forth by an advisory group to the National Heart, Lung Dr. Lasser led a study, which found that of 548 new chemical entities approved between 1975 and 1999, 16 were withdrawn from the market and 45 acquired one or more blackbox warnings. Dr. Lichtenberg tested the hypothesis that, all other things being equal, a person’s health is an increasing function of the vintage of the drugs he or she consumes, where vintage refers to the year the FDA first approved a drug.His overall conclusion is that, in the aggregate, the benefits to society of new drugs exceed their costs. DR.KAREN LASSER DR.FRANK LICHTENBERG 33 PharmaVOICE S e p t e mb e r 2 0 02 34 S e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 2 PharmaVOICE VALUE of drugs R B and Blood Institute in May 2001, found that 36.5 million Americans should be taking cholesterollowering drugs, leaving 28.3 million Americans untreated. According to the Institute’s director, if the recom mendations were followed, heart disease would no longer be the leading cause of death. This would, indeed, increase spending on prescription drugs, but industry advocates say, the return on investment is obvious. The majority of growth in prescription drug spending can be attributed to the fact that more people are getting more and better medicines, and not to price increases. In 2000, prescription drug spend ing increased 14.7%, but only 3.9% of the increase was due to price increases. Risk management In addition to their added costs, critics raise other concerns regarding new drugs, particularly their risk to the general public. This spring, a study in The Journal of the American Medical Association concluded that serious adverse drug reactions “commonly emerge after FDA approval. The safety of new agents cannot be known with certain ty until a drug has been on the market for many years.” Karen E. Lasser, M.D., a physician and researcher at Cambridge Hos pital in Massachusetts and a research instructor at the Harvard Medical School, led a study, which found that of 548 new chemical entities approved between 1975 and 1999, 16 were withdrawn from the market and 45 acquired one or more blackbox warnings. However, in an editorial, also published in The Journal of the American Medical Association, Robert J. Temple, M.D., and Martin H. Himmel, M.D., both of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Policy, Food and Drug Administration, note: “Premarketing trials in a few thousand (usually relatively uncomplicated) patients do not detect all of a drug’s adverse effects, especially relatively rare ones. Frequent postmarketing labelling changes are therefore inevitable and should be anticipated.” According to Dr. Lasser’s study, the estimated probability of a new drug acquiring blackbox warnings or being withdrawn from the mar ket over 25 years was 20%. New drugs had a 4% probability of being withdrawn from the market over the study period. Half of withdrawals took place within two years of a drug reaching the market. The study states ADRs come to light after drug approval because pre marketing drug trials often lack the power to detect them and have limit ed followup. Dr. Lasser’s study offers several recommendations. For exam ple: the FDA raise the threshold for new drug approval when safe, effective alternatives exist or when a new drug treats a benign condition; clinicians avoid prescribing new drugs when older, equally effective drugs are avail able; and, to help raise the level of ADR reporting, other reporting meth ods, such as patientinitiated reporting should be explored. “We’re not saying that these recommendations are going to eliminate the problem,” Dr. Lasser says. “The problem can never be eliminated because there is always going to be a drug that’s studied in the premar keting period and it’s only when it’s exposed to millions of people that problems are picked up. So, it’s inevitable that some drugs are going to have problems. But there are ways to mitigate the risk.” Balancing act Dr. Temple and Dr. Himmel say Dr. Lasser’s observations will help physicians in deciding whether or not to prescribe a new drug, but they question some of the analysis, for example the claim of a 20% risk of with drawal or blackbox warning for new drugs, since the early detection of ADRs in recent years may mean fewer late discoveries. They postulate that it is incorrect to describe the introduction of unsafe drugs as frequent; the analysis of drugs by Dr. Lasser et al actually demonstrates that ADRs of suf ficient importance to change the role of a drug in practice are uncommon. The small sample of people in clinical trials means the rare effects of a new drug may not be observed until postmarket. “But that has to be put into perspective,” Dr. Lichtenberg says. “Sup pose that a new drug was approved, and after five or 10 years we find out that 20 people died from the drug. Of course, that’s tragic. But put that into context. How many lives were saved or lifeyears were gained from the drug. And it seems to me the study (by Dr. Lasser et al) is only look ing at the down side. They’re saying that there are risks and these risks materialize over time, and that’s true. But researchers don’t want to only look at the risks. What really needs to be looked at is the net benefit, the benefit minus the risk, and I believe I am measuring that.” Fred Telling, Ph.D., VP of corporate policy and strategic manage ment at Pfizer Inc., says the company largely agrees with Dr. Temple and Dr. Himmel. “The probability of serious adverse reactions is going down, proba bly, not up, because we learn more, we learn how to identify risks ear lier,” he says. “Physicians have to make judgments, when they treat patients, on what is in the best interest of the patient. But, generally, there is no good reason to conclude that new products are not appro priate for patients. On balance the benefits that are associated with new products are much greater than the risks they pose.” According to PhRMA, the drug approval process in the U.S. takes 10 to 15 years. The FDA has maintained the same, consistent safety record through the 1980s and 1990s. In both decades (239 new molec ular entities approved in the 1980s and 379 new molecular entities approved in the 1990s), the percentage of products withdrawn for safe ty reasons ranges between 2% and 3%. F PharmaVoice welcomes comments about this article. Email us at feed [email protected]. Experts on this topic Martin H.Himmel,M.D.Deputy director of drug safety, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Policy, Food and Drug Administration, Rockville, Md.;CDER is a consumer watchdog that evaluates new drugs before they can be sold Alan Holmer.President, the Pharmaceutical Research Manufacturers of America (PhRMA),Washington,D.C.; PhRMA represents the country’s leading researchbased pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies Karen E. Lasser,M.D.Physician and researcher at Cambridge Hospital, Massachusetts and a research instructor at the Harvard Medical School, Boston Frank Lichtenberg,Ph.D.Courtney C. Brown professor of business at Columbia University Graduate School of Business,and research associate with the National Bureau of Economic Research, NewYork FredTelling,Ph.D.VP,corporate policy and strategic management,Pfizer Inc., NewYork;Pfizer is a research based pharmaceutical company with global operations Robert J.Temple,M.D. Director, Office of Medical Policy, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, and acting director of the Office of Drug Evaluation I (ODEI), Food and Drug Administration, Rockville, Md.;CDER is a consumer watchdog that evaluates new drugs before they can be sold